How NY leveraged federal money better than NJ after Superstorm Sandy

Flooded street under the Manhattan Bridge in Brooklyn, N.Y. on Oct. 29, 2012. (AP Photo/Bebeto Matthews)

In the two-and-a-half years since Superstorm Sandy many people have puzzled over the question of why New Jersey has received substantially less federal aid than New York, even though both states suffered roughly the same amount of damage — close to $37 billion.

In the two-and-a-half years since Superstorm Sandy many people have puzzled over the question of why New Jersey has received substantially less federal aid than New York, even though both states suffered roughly the same amount of damage — close to $37 billion.

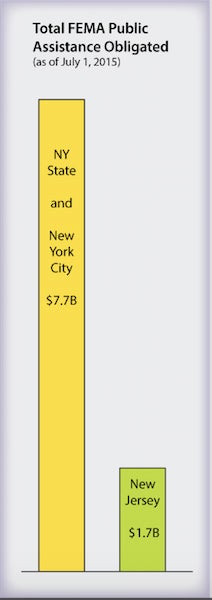

Much of the focus has been on Community Development Block Grants, where New Jersey got about half as much as New York state and New York City combined. But another metric in which the difference between the two states is most glaring is FEMA Public Assistance grants, which are used to help the state and local municipalities conduct both emergency and long-term infrastructure repairs after a disaster. To date, New Jersey has received just $1.7 billion in FEMA public assistance, compared with $7.7 billion for its neighbor across the Hudson.

Why such a big gap? The state office of Recovery and Rebuilding referred inquiries to the governor’s press office, who didn’t respond to a list of detailed questions. After speaking to a number of other officials in both New Jersey and New York, however, NJ Spotlight has been able to piece together a series of explanations.

To a certain extent, the disparity between the two states appears to be justified; both suffered enormous losses, but their damages were unique and called for different types of federal help.

New York faced a multitude of expensive infrastructure repairs, while New Jersey’s damage had a greater impact on individual homeowners, who wouldn’t have been eligible for public assistance.

Still, some critics speculate that New Jersey probably could have gotten more than it did from FEMA if it had handled the recovery differently, putting greater numbers of qualified and experienced people in charge of the process and being more proactive in its efforts.

“New York is very astute,” one source interviewed for this story said. “They’ve got it down. I’m not so sure that our friends in New Jersey have.”

Using the feds money to get more money

In order to receive FEMA public assistance dollars, a recipient would normally be required to spend a quarter of the total project cost upfront, in return for a 75 percent match from the federal government, but lawmakers successfully lobbied FEMA after Sandy so New Jersey, New York and other applicants only had to contribute one-tenth of the cost out of their own pockets for eligible projects.

Still, in the midst of a budget crisis, Trenton didn’t exactly have much spare cash lying around, so to come up with the money, it did what other states have done and earmarked a portion of the $4.2 billion it received in Sandy Community Development Block Grants to cover its local-match obligations. Although CDBG funds originate from another federal source — the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development — states realized after Hurricane Katrina that they could employ creative bookkeeping to count a portion of HUD money as their “local” contribution for the purposes of FEMA and other federal agencies, and they’ve been doing it ever since.

New Jersey initially allocated $275 million for this purpose, but as the recovery went on, the needs of displaced homeowners and renters continued to grow, with more than 40,000 primary homes and 16,000 rental units having sustained “severe” or “major” damage. Thus, the fund was raided several times to provide more money for the RREM grant program, as well as a new program for low- and moderate-incomehomeowners.

“Given the sheer breadth of housing damage and the number of homes that are required to be elevated, the state recognized that the costs of repairing owners’ primary residences and rental units would be massive,” said Department of Community Affairs spokeswoman Lisa Ryan. “Also, the state observed in the months after Sandy that many households displaced by the storm were seeking intermediate or long-term rental housing at a time when rental-housing stock was significantly depleted because of storm damage. Understanding that this confluence of events threatened to drive up rental prices for Sandy-impacted families, including those of limited financial means and those with special needs, the state decided to direct most CDBG Disaster Recovery funding to housing, since shelter is one of the basic human needs.”

That meant that when all was said and done, just $225 million was left to meet the state’s local match obligations with FEMA, as well as cost shares for water and wastewater system assistance through the EPA and transportation assistance through the Federal Highway Administration.

By comparison, New York State allocated $508 million out of the $4.4 billion it received, and New York City — which got $4.2 billion in HUD funding — chose to earmark over $1 billion, a quarter of its total amount, to cover its local-match obligations. With less demand for its housing program, however, the city had the liberty to do that, explained Amy Spitalnick, a spokeswoman for the Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget.

“I also think the higher local match in New York City is a logical result of the very significant storm damage to our urban infrastructure, such as schools, public hospitals, roads and bridges, and wastewater treatment plants. While our population [in the affected areas] might be slightly lower than New Jersey’s, it’s much more concentrated, which means more of our infrastructure felt the full brunt of the storm,” she said, adding that repairs to flooded tunnels and subway lines are more costly.

“New Jersey primarily had beaches and old towns with little value,” agreed another official. “I know they’re iconic towns, but the infrastructure is old. So you lose a couple of piers, you lose some beach … For what it cost to fix NYU [Langone Medical Center], you probably could have rebuilt half the coastline of New Jersey,” he said.

While New Jersey, New York City, and upstate New York (including Long Island) each received separate batches of CDBG funding and made their own choices about how much of that money to spend on local matches, FEMA’s decision to obligate $7.7 billion in public assistance for New York was based on the damages incurred and local matches paid by the city and the rest of the state combined. So infrastructure damage to the city alone could have easily had a significant impact on the amount of overall funding the state received, even if other areas weren’t hit as badly. In addition, New York officials note that damage from two other disasters that impacted their state — Hurricanes Irene and Lee — were also incorporated into FEMA’s funding equation.

It’s worth noting as well that New York City and New York State’s combined CDBG funding totaled more than twice what New Jersey received. So it was much easier for them to cover their housing needs and still have a sizable chunk of money left over to spend on local matches to access the FEMA funding to begin with.

But with just $225 million to spend, New Jersey was more constrained in the number and size of FEMA projects that it could request.

__________________________________________________

NJ Spotlight, an independent online news service on issues critical to New Jersey, makes its in-depth reporting available to NewsWorks.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.