Why are so many more children nearsighted these days?

One in three Americans now have myopia. Kids who spend lots of time indoors are five times more at risk of developing it, research shows.

(LGreen/BigStock)

How do we help children thrive and stay healthy in today’s world? Check out our Modern Kids series for more stories.

It’s time to take a closer look at nearsightedness and children.

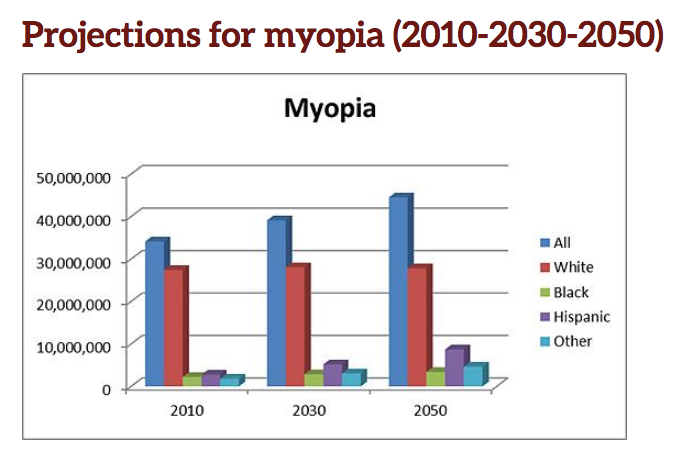

Why now? Because the American Optometric Association says the condition, also known as myopia, now affects 1 in 3 Americans. That’s a huge jump from two decades ago, and the numbers are only expected to climb. Health experts, including the World Health Organization, say nearsightedness is an epidemic in numerous parts of the world.

Among teens in the United States, for instance, about half are now affected.

And in some parts of China, 9 out of 10 are nearsighted.

Myopia lasts a lifetime. Here’s a quick primer:

Why do kids become nearsighted?

Myopia typically affects children because their eyes are still growing. Even the eyes of a toddler can become myopic.

Why is that?

Genetics is one factor. But research also shows that, for the most part, children who spend lots of time indoors are five times more at risk of developing myopia than those who don’t. If they are involved in lots of close-up viewing, the risk can increase a whole lot more.

Why is staying indoors an issue?

Because inside doesn’t have what’s outside: daylight. Daylight can stave off myopia’s progression.

And that happens how?

For one, it increases vitamin D levels. Researchers also are looking at dopamine, a chemical that sends signals between brain cells and plays a role in eye development. (Dopamine also is the chemical associated with pleasure.) In animal studies, daylight activates the dopamine byproduct that stops abnormal eyeball growth.

So daylight puts the brakes on myopia. Can it stop it?

The research is still up in the air. But it does show that someone would need to be outside about two hours nearly every day to be at the lowest risk of developing myopia. And these days, children aren’t getting those two hours.

Pediatrician Aimee Goodman said that for many years she regularly tested the vitamin D levels of sedentary kids she saw in her Hightstown, N.J., practice. The majority were myopic.

“Across the board, there were dramatic declines,” she said, noting that vitamin D also is needed for bone growth.

Does sunscreen block the UVB rays that help in making vitamin D?

No, sunscreen doesn’t get in the way, says a dermatology study from May 2019.

Lack of vitamin D seems like a real health problem. Is the message getting out?

That’s a big question. Obviously, the close-up viewing kids do happens at home, at school, in cars, and just about everyplace else. Kids use screens for practically everything; it’s likely their parents do, too. Health care professionals have pretty much abandoned the notion of cutting back on screen time to solve the myriad physical and psychological issues now associated with excessive screen use.

Yet research points out both benefits and negative outcomes of screen use. For example, a recent email from MedPage Today contained an article discussing how kids with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder can benefit from playing video games

for short spurts during the week, while another huge study examined kids with mental health issues blamed on screen use.

Here’s a radical idea, several experts say: Avoid many of the problems — including nearsightedness — in the first place by encouraging outside, unstructured play.

The fine details

If you’re nearsighted, you can clearly see a few inches in front of you. Beyond that, things get blurry.

In a normal eye, light enters through the cornea. The eye’s lens then focuses the light on the retina, vital layers of tissue at the back of the eye. Here, the light is translated into code before it’s sent to the optic nerve, where the brain will figure out, oh, that’s a truck or that’s a frog.

In a nearsighted eye, the light lands before the retina, and the eyeball reacts by elongating. That sometimes causes the retina to tear. Without help from prescription eyeglasses or another correction, the nearsighted eye works hard to see, risking the eye’s health and function.

Special contact lenses worn at night — called ortho-k lenses, short for orthokeratology — can help reduce the blur by reshaping the cornea temporarily. Late last year, the Food and Drug Administration approved a soft contact lens designed to slow myopia’s progression.

In the past, typically only older adults experienced retinal tears. Not now.

“We have had teens who had retinal surgery” to repair the tear, said optometrist Nicholas Despotidis, who specializes in pediatric myopia. Years ago, he said, the average age for the condition was 12; today, it’s 7. He has treated children as young as 5 with the specialized contact lenses.

When pediatrician Aimee Goodman updated her vision-testing equipment about eight years ago, she found she could screen much younger children.

“Over time, I found myself referring more and more [patients] to optometrists and ophthalmologists … the parental attitude was ‘Thank goodness for picking this up. …’ At the same time, there was a lot of resistance: ‘I will not get my kid tested for glasses.’’

Myopia correction is usually not covered by basic health insurance plans.

Let’s go outside and play

Since he began his practice in Hamilton, N.J., 30 years ago, Despotidis said, the number of youngsters who have needed glasses to correct myopia has doubled. With fellow optometrist Noah Tannen, he wrote A Parent’s Guide to Raising Children with Healthy Vision. The book urges parents to help their children prevent myopia from even starting, as opposed to thwarting its progression.

Despotidis is a huge advocate for unstructured, outdoor play. Some of his patients’ parents listen, sort of, he said — their kids walk the dog, visit parks, join marching bands.

But the experts point out that unstructured playtime lets children solve their own problems and learn to cooperate and understand the ins and outs of human interaction. That doesn’t happen in a structured play environment.

“Parents think the world is a lot scarier, but research doesn’t bear that out,” said Scott Roth, a school-clinical psychologist in Middlesex County, N.J. “Parents would prefer to put their kids in six different dance classes than have them play on a neighborhood block.”

All of this, some experts say, suggests that rethinking what your child does during free time — and recognizing the importance of this free time, its location, and that it could literally affect the rest of your child’s life — might be in order.

So is rethinking how you, as a parent, interact with your child, they say. Nearly every expert interviewed for this article questioned what message parents send their little ones when they are on their phones while their toddlers idle in a shopping cart or eat in a restaurant high chair.

Technology is a part of modern life, though, and there’s no easy way around it for modern parents and modern kids.

The screened elephant in the room

The question should be, “How does the technology work for the kids?” said adolescent physician Megan Moreno, a professor of pediatrics at University of Wisconsin, Madison. “Why aren’t the kids getting outside? What is the reason? Is it the screen’s fault or part and parcel of our society? Taking away screens isn’t part of the solution.”

There’s no devil or angel, no universal number representing the time children can use iPads before their eyes vacate their sockets. Not all screen time is created equal.

The challenge is real for parents to open their front doors and let their kids just go, said Samuel Wang, a professor of neuroscience at Princeton University.

He and his wife planned that their daughter, now 12, would escape a myopic future, because he is myopic. So she played outside, read outside. But genetics won out. Their daughter now has been fitted with the special contact lenses, and she has been restricted to using a flip phone.

Wang is a true believer in the power of daylight.

“Outdoor time is the number one medicine for preventing myopia and interrupting [eyeball elongation], per the study finding,” he said.

“Early in life, children are not cognitively ready for screen time. If you are busy, the screen is super-convenient. But, be careful, it is time spent away from human development.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.