What is race? It isn’t skin color, as some young people are learning

It’s a tough question: Why do we look different? As one high school’s syllabus puts it, race is “both a biological myth and a social reality.”

Listen 5:50

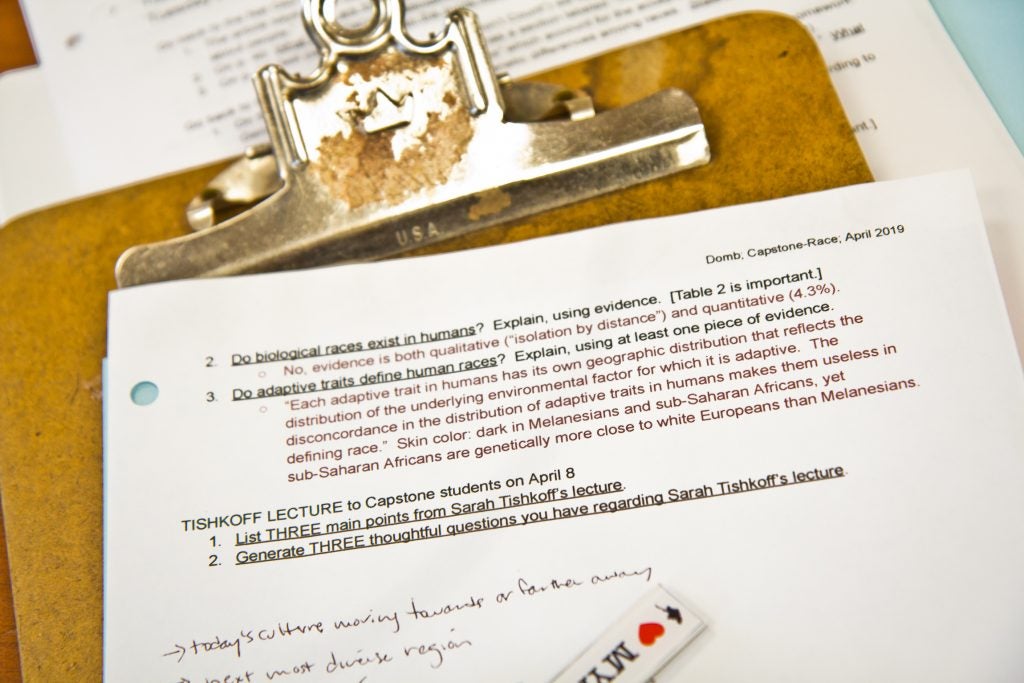

The Lawrenceville School teacher Leah Domb helps students discuss a lecture on race and biology by Penn professor Sarah Tishkoff. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

How do we help children thrive and stay healthy in today’s world? Check out our Modern Kids series for more stories.

—

Sarah Tishkoff, a professor of genetics and biology at the University of Pennsylvania, gives a guest lecture to science classes at the Lawrenceville School, a private school in Lawrence Township, New Jersey.

The topic is race, and she points out the big problem — that biologists cannot define it. The class syllabus explains race is “both a biological myth and a social reality.”

Tishkoff asks the students how people classify race, and one immediately puts up his hand. His answer: skin color.

“And that’s what I hear at every undergraduate course I’ve lectured in: Whenever we talk about this, first thing that people say is skin color,” Tishkoff says. “And we’re able to show that that’s just a terrible classifier of race because skin color is an adaptive trait.”

Populations adapt to how much ultraviolet light they’re exposed to over generations. Thus we have different skin colors. And genetically, that has absolutely no connection to other traits, like intelligence.

Race is not a real biological category — human beings are more than 99 percent genetically identical. But for centuries, junk science has been used to justify racism and social hierarchies by suggesting significant biological differences between groups of people.

There are differences along racial lines in the United States. But it’s hard to say whether those differences are because of any inherent biological differences, or because of social factors like decades of institutional racism leading to lack of access to health care and people living in drastically different environments.

Some biologists argue that children should grow up learning the truth behind the science of race from a young age.

Leah Domb, a science teacher at the Lawrenceville School, created this class with her colleagues because she has been teaching human evolution for 15 years, and her students always have the same questions: “Why do we have different races? Why are races different from each other now?”

And she understands why: Students come across race everywhere.

The day after this spring-term lecture, the class discusses what they’ve heard. Chase Johnson, a senior who is about to graduate, talks about choosing his race before taking the SAT.

“It’s just too confusing … confusing social for biological and checking boxes on certain exams just reinforces that even more, because me personally taking the exam, I would think maybe they will view me a certain way or ascribe some sort of trait to me by checking a box.”

The students talk about how to deal with the knowledge that the racial categories people use in everyday life don’t correspond to actual biological categories.

Johnson is African-American and recently considered which college to go to:

“If there is no one that looks like me at a certain school, I would probably feel less inclined to go there because I feel like I wouldn’t be able to relate as well, with people,” he says. “But at the same time, you have to keep in mind that, like, race doesn’t exist … everyone is pretty much genetically equal … you just have to keep an open mind.”

Domb says a lot of students experience this shift when they learn about the lack of science behind what we think of as race. Students in the class also learn the history of racism and racial hierarchies, which is a big part of why people have the idea that race is connected to real biological differences. The Lawrenceville School will offer this class again next year in the spring.

“We actually want to start introducing this course at an earlier stage in the Lawrenceville student career, so that they can bring back those discussions within the school as they’re actually here, rather than just in their senior year,” Domb says.

Emily Berman has been doing exactly that. She’s a science teacher at Blackstone Academy Charter School in Rhode Island, and for the past few years, she’s been teaching race to ninth-grade science students.

It’s one of the school’s most popular units, Berman says, and students come out with a different way of seeing the world.

“They question the Census, they question things the current administration has said, they question what they see in the magazines, what they see in media, what they see on Instagram …”

This is such an important topic, Berman says — it touches on science and history, and builds data-analysis and critical-thinking skills — that science teachers and history teachers or maybe even math teachers could tackle a part of it.

She has presented her work to other science teachers at conferences, and their biggest concern is how they can find time for this.

Berman acknowledges that she has the luxury of being at a supportive school where she can work together with a history teacher. But teachers at other schools can start addressing the issue of race, even if they use other people’s work and just discuss it for a day, she says.

“That’s better than never addressing it at all and acting as if it doesn’t exist and doesn’t affect science and society,” she says.

Because there are entrenched ideas about race, teaching the science of race can start difficult conversations, even for her university colleagues at Penn’s medical school, Tiskoff says.

“For a long time, I would say that many of my colleagues have avoided talking about this, because it’s often seen as a contentious subject,” she says. “But I feel like we have to talk about it because if we don’t, it’s just going to promote misunderstanding.”

Anita Foeman, a professor of communication studies in West Chester University, founded the DNA Discussion Project, which provides DNA ancestry kits to students and others in the community so they can test themselves and start a conversation about race and identity.

That sometimes leads to unexpected results, she says — like people from the Caribbean finding Asian ancestry, or African-Americans finding European ancestry. Foeman says that leads people into learning the biology behind race and ancestry, and how humans are more than 99 percent genetically the same.

“One of my favorite statements that I’ve had people make several times over the course of this project: ‘Gee, if I didn’t know this about myself, maybe I have been wrong in judging other people.’ And you just find that having people look at race in this way is a way of humbling us all,” she says.

“I’ve talked with groups who are fourth graders, and I’m shocked to the extent at which they get it.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.