Vietnam: The war that was waged in my head

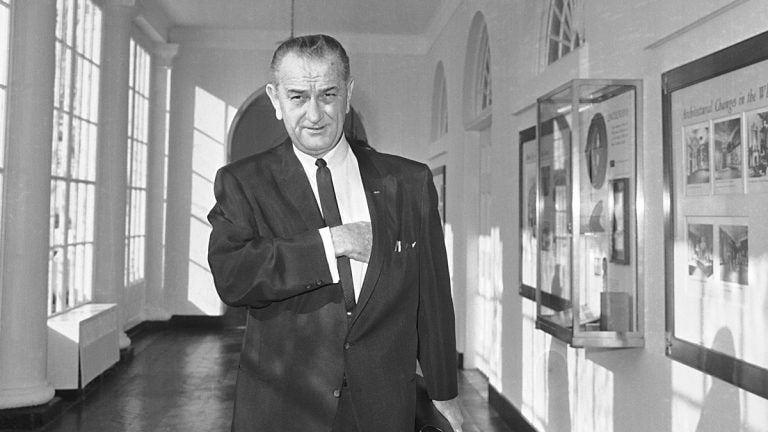

President Lyndon Johnson walks from his office in the White House to a studio in the Executive Mansion to address the nation on the bombing of North Vietnam, Jan. 31, 1966. (AP Photo, file)

In the winter of my 13th year, I made a momentous life decision. I marched into my parents’ suburban kitchen and declared that when I got old enough, I would “go to Vietnam and kill commies.”

This story is part of a WHYY series examining how the United States, four decades later, is still processing the Vietnam War. To learn more about the topic, watch Ken Burns and Lynn Novicks’ 10-part documentary “The Vietnam War” running Sunday, Sept. 17 at 8 p.m. through Thursday, Sept. 28, on WHYY-TV.

—

In the winter of my 13th year, I made a momentous life decision. I marched into my parents’ suburban kitchen and declared that when I got old enough, I would “go to Vietnam and kill commies.”

I figured: Why not? It was the patriotic thing to do. The landslide-elected president had just sent in the first U.S. combat troops, to defend something called Da Nang — I had no idea what or where Da Nang was, but it sounded exotic — and my adolescent adrenaline was bestirred by “The Ballard of the Green Berets” (Silver wings upon their chest / These are men, America’s best), which topped the radio pop charts. I wanted that manly chest, to be one of the best, and I was always in thrall to AM radio.

My father shrugged me off, telling me with full confidence that this small war in March ’65 would be long over by the time I turned 18 in late ’69. I felt deflated, but surely he was right, because all the news out of Washington — which came to me in short bursts on NBC’s “Huntley-Brinkley Report” and in terse Associated Press stories in the local hick newspaper — made it clear that Uncle Sam would go in hard, kick commie ass, and get out fast. Our government said it, so it had to be true.

My kitchen announcement came to mind this week while watching Ken Burns’ PBS “Vietnam” series, a meticulous depiction of American deception and hubris runneth over. None of those truths were known back in March ’65. I was like most everyone else, cocooned by what I didn’t know. Like millions of other Baby Boomers, only a minority of whom succumbed to the draft, my personal Vietnam was the war that was waged in my head. It changed me forever.

I was not a total innocent back then; the JFK assassination, which happened while I was in math class talking with my seatmate Sue Ann, had shattered the childlike myth that nothing could go wrong for America, but the new president’s Warren Commission had said it was just a lone disgruntled assassin, so that was that. And Vietnam looked like a trumpet’s call to arms. I had grown up hearing about The Iron Curtain and watching TV shows that featured global maps with a red stain oozing across nations. If “we” didn’t stop “them” far away, “they” would spread that stain to California — the idyllic home (as far as I knew, from TV and AM radio) of carefree blonde surfers and groovy go-go dancers.

But weird stuff started to happen in ’65. We kept bombing and bombing — it was called Rolling Thunder, a perfect name for American muscle — but the fighters from the North refused to come to their senses and surrender. They kept attacking places like “Phuoc Long,” which, for all I knew, was probably the name of an entree in my town’s Chinese restaurant, but our president said all was well, he would keep sending troops — 40,000 here, 35,000 there — and he told us, “We cannot be defeated by force of arms.”

I can’t precisely remember when I decided that Lyndon Johnson was full of it. (He was actually full of it in July ’64, when he announced on TV that North Vietnamese fighters in PT boats had attacked us in the Gulf of Tonkin; this became the basis for his blank check to wage war, but we didn’t learn that he’d fabricated the Tonkin incident until White House tapes were released decades later.) But my budding skepticism about LBJ was stoked by the body count reports that became a regular feature on the nightly TV news shows.

Huntley and Brinkley, the NBC anchors, would pass along the official U.S. government stats: Americans killed and wounded, Vietcong killed and wounded, numbingly rendered on screen. Week after week, the Vietcong totals wildly exceeded the American totals, but we didn’t seem to be winning. And it was around that time that I was watching my favorite music show, “Hullabaloo,” and a gruff guy named Barry McGuire came on to perform his dystopic hit, “Eve of Destruction.” (Introduced by Jerry Lewis, no less.) And he sang:

The eastern world, it is explodin’,Violence flarin’, bullets loadin’,You’re old enough to kill but not for votin’,You don’t believe in war, but what’s that gun you’re totin’…

That definitely twisted my ‘tude. And as the grind of war accelerated, as the American body count stats escalated, the soundtrack of my life changed accordingly.

We didn’t have iPhones to serve up instant info at a finger’s touch; what we had was music. I wasn’t a cool kid, but I had some cool friends who knew the cool message music — like Country Joe McDonald’s “Fixin’ to Die Rag” (Be the first one on your block / To have your boy come home in a box), and Bob Dylan’s “Masters of War” (You fasten the triggers / For the others to fire / Then you sit back and watch / When the death count goes higher).

And I had a cool high school teacher, whose name was Joe LaValley, play The Mothers of Invention in class — most notably, “Trouble Every Day” (about desensitized violence) and “It Can’t Happen Here,” the Mothers’ sarcastic swipe at suburban ennui:

Plastic folks, you know it won’t happen here You’re safe, mama, you’re safe, babyOh, we’re gonna get a TV dinner and cook it up Go get a TV dinner and cook it up cook it upOh, and it won’t happen here …

I probably reached my point of no return in January ’68, when LBJ’s assurances and General Westmoreland’s “light at the end of the tunnel” promises were rendered preposterous by the Viet Cong’s massive Tet offensive. But I may have irrevocably turned off in ’67, when Pete Seeger taped a performance of “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy” for the Smothers Brothers variety show — only to be axed by the CBS overlords, who hated a line that was aimed at LBJ (Waist deep in the big muddy / And the big fool says to push on). Seeger was barred from singing his song until early ’68, when CBS finally gave in, its censorous treachery exposed.

So I owe my rabid skepticism — especially about government — to the grind of growing up during Vietnam. Young people today are often astonished to hear that there once was a time when kids like me reflexively believed our leaders. That faith is another casualty of Vietnam. The upside is that we’re far less naive, far more vigilant, far more willing to call out a president and question authority. For that, I thank the ’60s. If only we could have learned those lessons without leaving 58,000 dead carved on a Mall memorial.

—

Follow me on Twitter, @dickpolman1, and on Facebook.

To learn more, watch Ken Burns and Lynn Novicks’ 10-part documentary “The Vietnam War” running Sunday, Sept. 17 at 8 p.m. through Thursday, Sept. 28 on WHYY-TV. WHYY members will have extended on-demand access to the series via WHYY Passport through the end of 2017.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.