Taking it to the streets, then and now

The author is shown, second from the left, following his release from jail in July with other members of protest group Bowling Green Patriots. (Courtesy of Samuel S. Flint)

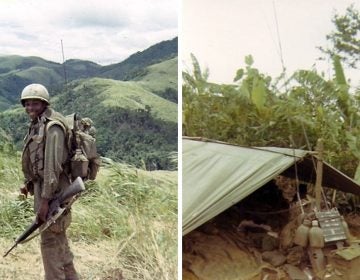

This story is part of a WHYY series examining how the United States, four decades later, is still processing the Vietnam War. To learn more about the topic, watch Ken Burns and Lynn Novicks’ 10-part documentary “The Vietnam War” running Sunday, Sept. 17 at 8 p.m. through Thursday, Sept. 28, on WHYY-TV.

—

Twice in my life I went to Washington, D.C., intending to commit civil disobedience. The first time was in October 1967, to stop the war in Vietnam; the second was in July 2017, to stop the repeal of Obamacare. Working hard locally was an insufficient outlet for my rage. I needed to express it in the belly of the beast. Both times I felt I had to do everything I could to prevent senseless loss of life; both times I knew I was on the right side of history. That’s where the similarities end.

On July 10, more than 100 of us gathered at a D.C. union hall. We had come from as far away as Fairbanks, Alaska, to make our voices heard. And, given today’s social media outlets, we felt confident that our actions would be seen, despite our modest numbers. We were organized into a dozen subgroups of 10 to 12 people and driven to targeted Senate and Congressional offices. Our organizers fed us before we left and gave the 80 of us who planned on arrest a $50 bill to pay the expected fine. We arrived simultaneously at our designated offices where pre-selected medically fragile speakers boisterously told their personal stories as the whole group demanded that Obamacare be kept. We ranted and chanted until the Capitol police warned us to desist or face arrest. Some of the group backed off, and the rest of us committed the planned civil disobedience.

They marched us off in handcuffs to vehicles that held about a dozen prisoners and deposited us into an industrial holding area, where we sat for eight hours (still cuffed) before being fined and released. We walked out and were greeted by a small crowd of congratulatory supporters who offered us cold pizza and warm smiles. The police who arrested and detained us were professional, almost nonchalant about the whole kabuki theater we perpetrated, and despite the discomfort from the plastic ratcheted handcuffs, the entire affair was … civil.

It was different on October 21, 1967, when 100,000 of us assembled at the Lincoln Memorial. Every demographic group was represented, but we were predominantly young, white, middle-class, and male. We came to oppose the war, to fight the draft, to fight the oppressive society that sent hundreds of thousands of our generation to kill the Communist boogeyman. We believed our country had no legitimate right to intervene in a civil war halfway around the world; that the saturation napalm bombing of a largely rural, peasant, non-white society was genocidal; that the puppet regime in South Vietnam, installed and propped up by U.S. forces, never shared America’s democratic values. And we rejected the debunked notion that successful Communist revolutions would break out everywhere in Asia if “they” weren’t stopped in Vietnam.

A police officer is shown confronting the author at another protest in 1968. (Courtesy of Samuel S. Flint)

A police officer is shown confronting the author at another protest in 1968. (Courtesy of Samuel S. Flint)

When we took to the streets to support Obamacare, we understood that a small fraction of the country sought its repeal. Not so in ’67. Opposing us was the majority of the country, many of whom had family members who volunteered for the service or took the oath with pride when they were drafted. They were enraged to think that our generation wouldn’t whole-heartedly do the same as our fathers and uncles who put their lives on the line on Omaha Beach and elsewhere to protect our way of life. They wrote off the demonstrators as degenerate cowards, spoiled children with misguided commie beliefs, who should be spanked hard for their disloyalty. Several violent confrontations between protesters and the police broke out before and after the march on the Pentagon. Fifty years ago, civil disobedience wasn’t civil.

After the morning’s speeches and folk songs, the march from the Lincoln Memorial to the Pentagon commenced. We arrived to find the bayonet-exposed, battle-hardened 102nd Airborne dressed to kill. Machine guns and grenade launchers lined the Pentagon’s roof. Scuffles broke out. Tear gas was used to disperse the crowd.

By late afternoon nearly all the demonstrators boarded the busses that brought them to town and were headed home. The hard core dug in, squatting on the small plaza that abuts the Pentagon’s front door. Some folks broke out guitars, and we sang “We Shall Overcome,” other popular protest ballads, and yes, “God Bless America.”

In ’67 the authorities knew that only a rare account would make it into the public consciousness after the national news captured their footage for that night’s seven o’clock broadcast and the print reporters submitted their stories for the morning papers. The use of the media to exhibit primary source, ground-level action was in its infancy. Martin Luther King brilliantly exposed Southern brutality a few years earlier, and just a few months later, the Chicago police riot would be witnessed live by millions as protesters chanted “The whole world’s watching.” But that night, when it got dark and the press left, independent witnesses were not to be found.

Around 10:00, several large vans rolled onto the plaza between the Pentagon and the troops lined up against the demonstrators. Blue-helmeted federal marshals started advancing toward the crowd with nightsticks in their fists and anger on their faces. We held our ground. Then the troops began stepping on and over the protesters and the marshals came in swinging. Blood flowed.

An experienced organizer grabbed a megaphone and told the crowd for their own safety not to resist arrest (for crossing a fire line I later found out). The marshals packed the vans with hundreds of protesters. I braced myself as they came right up to me, but apparently the last van was full. The attack subsided, and I wasn’t taken.

With the exception of one story several weeks later in The Atlantic, these events were never reported by any other national news outlet. Fortunately the ubiquitous video camera and the 24-hour news cycle would expose, if not prevent, such actions today.

—

To learn more, watch Ken Burns and Lynn Novicks’ 10-part documentary “The Vietnam War” running Sunday, Sept. 17 at 8 p.m. through Thursday, Sept. 28 on WHYY-TV. WHYY members will have extended on-demand access to the series via WHYY Passport through the end of 2017.

Sam Flint is a health policy analyst and advocate. He was an executive with the American Academy of Pediatrics for nearly two decades and taught public policy and health economics at three universities. Sam has authored more than 20 articles on Medicaid and health reform in a half-dozen peer-reviewed journals, and he has served as an expert witness in federal courts in several Medicaid cases addressing the rights of children to access medically needed care. Sam holds a B.A. from University of Rhode Island, an MSW from Florida State University, and a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. He and his wife Rebecca live in Media, Pennsylvania.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.