Saving Philly’s bats, one DIY condo at a time

A Penn project could help keep urban bats out of your attic and support them in their fight against a deadly disease.

Listen 1:06

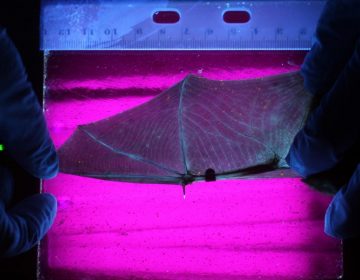

FILE - This undated photo from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service shows little brown bats with the fuzzy white patches of fungus typical of white nose syndrome, which affects at least 12 species nationwide. (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service via AP)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

On a recent fall afternoon, a group of University of Pennsylvania students converged around folding tables on the College Green to put the finishing touches on some newly created real estate: miniature wooden condos built to house the city’s dwindling bat population.

These “bat boxes” were the brainchild of Penn undergraduate Nick Tanner, who suggested the conservation project for Penn’s yearly Climate Week, a weeklong series of events that this year were focused on climate solutions. The idea was quickly taken up by the school’s Wildlife Futures Program, a conservation-focused partnership between the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine (Penn Vet) and the Pennsylvania Game Commission, which enlisted the school’s fabrication lab and facilities department to construct the boxes.

The boxes, which will be installed across Penn’s campus early next year, are designed to provide a safe habitat for two of Pennsylvania’s most common bat species — little brown bats and big brown bats — the former of which has experienced a catastrophic decline in its population over the past 15 years.

White-nose syndrome

Little brown bats used to number in the millions across Pennsylvania — but now, their numbers have fallen into the thousands.

“Around 2008 is when biologists started noticing declines of bats,” said Julie Ellis, an ecologist and co-director of Penn Vet’s Wildlife Futures Program, which facilitated the project. “In the case of the little brown bat, the population has declined by more than 90% since that time. It’s now designated as an endangered species.”

The reason: a fatal disease called white-nose syndrome.

White-nose syndrome is caused by a fungus that’s believed to have been introduced from Europe, and which infects bats during hibernation, growing along their muzzles and wings. The fungus itself is capable of damaging the wings — but what makes it so deadly is how it affects bats’ hibernation.

“During hibernation, bats reduce their metabolic rate and lower their body temperature to save energy over the winter,” Ellis said. “But hibernating bats that are affected by white-nose syndrome wake up to warm temperatures more frequently, which results in using up their fat reserves. And then they can starve before spring arrives. So you can imagine having a fungus on you might be irritating.”

While the bat boxes don’t defend directly against white-nose syndrome, Ellis says they will help support the overall bat population by providing safe places for colonies to hibernate, give birth and raise their young. Bats in urban areas sometimes struggle to find safe roosting areas due to a lack of trees — which can sometimes result in them moving into, and later being evicted from, people’s houses.

“They’re looking for warm spots in the summer,” Ellis said. “And, you know, heat rises, and they tend to be in attics, and most people don’t really want bat colonies in their buildings. So we’re creating additional habitat that they might not be able to find.”

Other efforts to fight white-nose syndrome

There isn’t yet a treatment for white-nose syndrome, but Ellis says the Pennsylvania Game Commission has been attempting to manage the disease by applying chemicals to roosting sites that can help inhibit the growth of the fungus, thereby disrupting transmission.

Game Commission biologist Greg Turner has also been exploring engineering experiments to increase the flow of cold air in caves and other roosting sites, after observing that bat populations in colder hibernation sites seemed to be less affected by white-nose syndrome.

“So it seems like if you lower the temperature, it makes the fungus less likely to infect the bats and keeps the bats from waking up as often during their hibernation in the wintertime,” Ellis said.

That means that the bats are more likely to hibernate undisturbed, without frequent awakenings, until spring.

“And once their bodies heat up, they can kick back the fungus because their immune system kicks back in and can fight the fungus off,” Ellis said.

Ellis says that locals can also help support area bats by building or buying their own bat boxes, participating in the Game Commission’s Appalachian Bat Count program, keeping their cats indoors and limiting the use of pesticides, which can cause health problems.

In return, Ellis says, people can expect summertime benefits.

“A single bat can consume up to 25% of its weight at a single feeding — and there are some estimates that some species can consume nearly a million insects per bat per year,” Ellis said. “Those insects include mosquitoes that spread diseases to people, like West Nile virus and Zika.”

Bats also reduce the need for pesticides, which can translate to substantial economic benefits for farmers and benefits to the environment overall.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.