‘Up close and personal’: Mütter Museum maps the spread of Philly’s 1918 flu epidemic

The Mütter Museum created an interactive online database that maps the 1918 flu epidemic as it swept through Philadelphia.

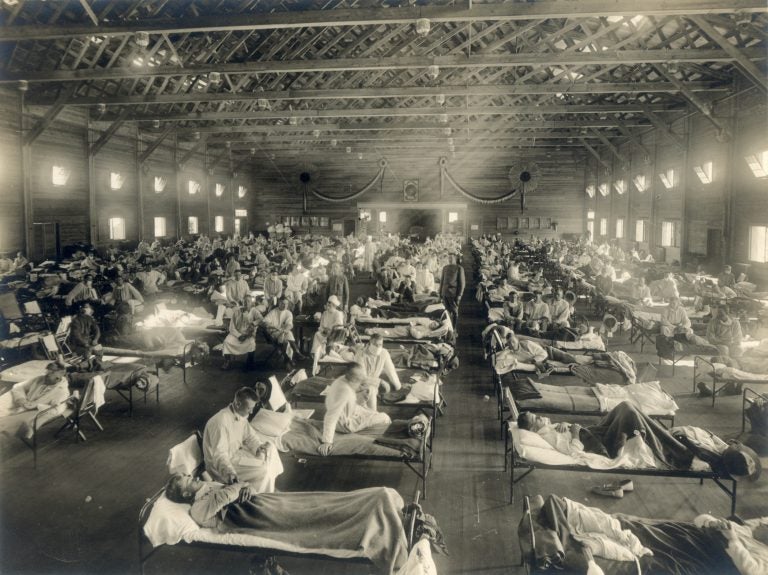

Emergency hospital during influenza epidemic, Camp Funston, Kansas, probably early 1918. (OHA 250: New Contributed Photographs Collection, Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine)

The numbers are staggering: 12,000 deaths in just six weeks. Before the flu epidemic of 1918 was done with Philadelphia, more than 20,000 people would die.

“To this day, nobody knows the precise death count globally,” said Mütter Museum director Robert Hicks. “It could be 100 million, could be 50 million, or somewhere in between.”

The numbers are so large it can be hard to wrap one’s head around it. So many people were dying daily in Philadelphia that coffins could not be built fast enough. Cemeteries resorted to using packing crates. Seminarians spent all day, every day, digging graves.

One hundred years later, the new exhibition at the Mütter Museum, “Spit Spreads Death,” tries to put a human face on what it calls the “landscape of death.”

“As a historical medical institution we think very much about the science part and not always about the personal and social aspects,” said project manager Nancy Hill. “We wanted to try to measure the social toll of these kinds of pandemics. It’s easy to think about doctors in rooms making decisions, but this has a human cost.”

When the Mütter Museum began looking into the historic epidemic five years ago, it discovered a trove of information in archives around the city, including tens of thousands of death certificates. Part of the project was to create a public online database of all those death certificates and place them on an interactive map.

Users can search by name or neighborhood to track how the flu swept the city.

“People could look up their home addresses to see if somebody died in their home or on their street in 1918, or see how the mortality came through over a period of weeks through their own neighborhoods,” Hicks said. “We did want this to be up close and personal.”

The exhibit also pulls from archives of local institutions. North Philadelphia’s Girard College saw a spike in orphans applying to the school because their fathers had died from the flu. The Catholic Archdiocese had taken photos of mass burials.

Drexel University’s costume collection provided one of the most poignant artifacts. In the fall of 1918, a young woman from New Jersey named Naomi Ford came to Philadelphia to do some early Christmas shopping for her family. She tagged the gifts with little hand-written poems and put them away to be given out at Christmas.

But Ford caught the flu and died on Oct. 21, having never had the chance to deliver her gifts. Her mother, grief-stricken, put the gifts in the attic where they stayed for generations. The boxes were discovered decades later and ultimately donated to Drexel University’s costume collection.

One of those, an embroidered purse still in its gift box tagged “For Cousin Helen,” is on display.

Since the Mütter Museum started collecting artifacts for this exhibition, Hicks said people are coming out of the woodwork with stories of their ancestors.

“These are families who may never have shared these stories outside their families,” he said. “These stories were told to us by people who, of course, were not alive in 1918. But the memory of the family trauma is ever-present in the families. This very impressive to us.”

Some of those stories are gruesome, according to Hicks, and some were almost comic: it was not uncommon to give children whiskey, sometimes several times a day, out of the belief that liquor would avert the flu virus.

“Whiskey was a very popular remedy. You’re going to take a hot toddy or take a shot of whiskey every couple hours,” Hill said. “Teenagers were kept perpetually buzzed for a week or two, to avoid catching the flu.”

Hicks and Hill want “Spit Spreads Death” to speak to contemporary issues with pandemics. These days, epidemics still occur because of the lack of communication and resources.

There was no unified national effort to fight the 1918 flu epidemic. The United States had entered World War I and President Woodrow Wilson did not want anything distracting the country from the war effort.

“The president of the U.S. never makes a public utterance of the flu. Everything is subordinate to the war effort,” Hicks said. “Patriotism was high. To criticize the government as maybe not doing enough for flu cases could be construed as criminal behavior.”

Medical research into the flu, some of which began in Philadelphia, would take decades to result in a cure. An effective vaccine could not be developed until the 1930s — more than a decade after many Philadelphians lost their lives.

“Spit Spreads Death” opens this weekend at the Mütter Museum and is planned to remain on view permanently.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.