Underwater mortgages hindering buyouts of flood-prone homes in N.J.

ListenThe Garboskis and the Dombrowskis are neighbors, couples in their eighties who have lived side by side for nearly five decades. Both were flooded during Superstorm Sandy; both have mostly finished fixing their homes.

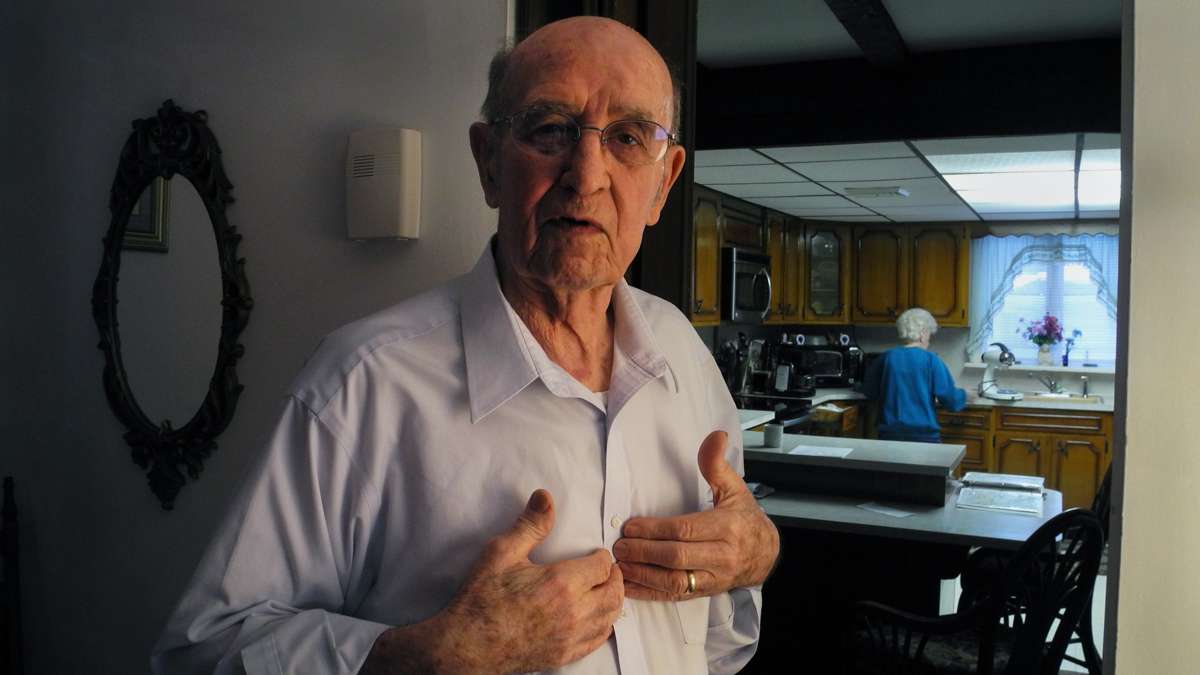

“I did everything myself except this boiler,” said Zigmunt Dombrowski, proudly touring his restored basement. “[Volunteers] ripped it out and I put it back. My electrical panel, everything, I did myself.”

Dombrowski lives in Sayreville, N.J., east of New Brunswick along the Raritan and South Rivers. His neighborhood has severely flooded three times in the last three years. The state wants to buy his house, the Garboksi’s, and some 1,300 other homes for their pre-storm value and demolish them. It’s part of a $300 million Blue Acres program, funded with federal Sandy aid. New York has launched a similar program.

But the process hasn’t moved as fast as the state and homeowners were hoping. Sixteen months after Sandy, more than 400 deals are in the works, many in Middlesex and Cumberland Counties, but only 44 have closed so far.

Assessments

One cause of the slow down is that many homeowners believe the state has not offered them enough money for their homes.

“The assessment process is a very sore subject with me,” said Dombrowski’s neighbor Don Garboski.

Garboski thinks his offer is at least $20,000 short, especially compared with an offer another neighbor received for a smaller home. However, he decided not to appeal his appraisal because he said he was told it the process might take five months and his offer could decrease upon review.

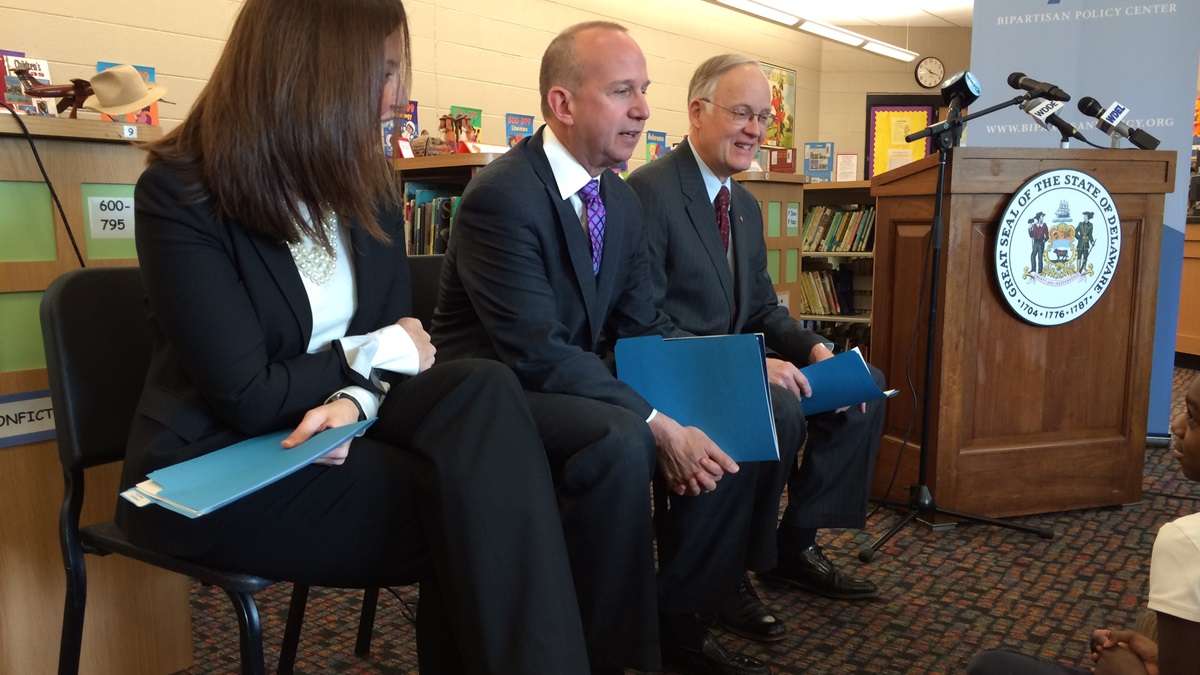

That’s not the state’s policy, according to Rich Boornazian, who runs New Jersey’s Blue Acre’s program, part of the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection.

Boornazian says the DEP did notice that appraisals done by one of the companies the state hired were consistently lower than others and he encourages those homeowners to appeal. Contrary to what Garboski has heard, Boornazian said that even if appraisals decrease upon appeal, the state would honor its original offer.

Since Garboski decided not to appeal, his closing is set for late spring, after which he and his wife will move to South Carolina. Knowing the home will soon be in the hands of a demolition crew, Garboski has stopped fixing small problems.

“This door knob that’s broken,” he said, jingling a latch that no longer works. “I refuse to have it replaced. Why fix it?”

He tells guests not to bother taking their shoes off.

“I don’t care if someone comes in with ice skates,” he shruged.

A few blocks down the street, Fran O’Connor, who actively advocated for the buyouts, also felt her offer was too low.

O’Connor and her husband were able to correct inaccurate information about the square footage of their house, which raised their offer by $10,000, but the couple also opted out of a formal appeal.

In mid-February, O’Connor took one last walk through her gutted home and turned the keys over to the state.

“Although we were not thrilled with [the offer] and wished it was a little bit more, we decided that it was time to move on,” she said. “We found a new house and we just needed to be done and closed.”

Underwater homeowners

Other delays have arisen from the surprising number of homeowners who are financially “under water.” They owe more on their mortgage than the house was worth before the storm.

“What we didn’t expect was the 30 percent rate of people that were ‘underwater’ on their mortgages,” said Boornazian. “So that’s a tough one. The state doesn’t have extra money to pay more than the appraised value.”

The state is now negotiating with banks to see if they will accept less than full repayment of a mortgage, which, again, takes time.

Low interest in coastal communities

Additionally, the state has to wait for a second round of federal funds to be released before it can make more offers. Once that money is approved, Boornazian says he’ll finally start buying up properties at the shore, though in much smaller blocks — for example, there are three lots in Beach Haven that could provide parking and a dog park.

But there hasn’t been as much interest from the coastal communities.

“Nobody is going to sell us their beachfront house,” says Boornazian. “So let’s go there. You know, I’ve been to [Long Beach Island] maybe four or five times talking to communities there and no one is selling us beachfront.”

In Toms River — which has the highest flood insurance payouts in the state over that last four and a half decades — 25 homeowners have applied to Blue Acres. Boornazian does not believe those properties are actively being pursued for buyouts.

Mayor Tom Kelaher says he’d support those applications, but he also thinks Sandy was a one-shot deal and is skeptical that buyouts would make a difference in Toms River.

“All of the flooding that we had, 10,000 homes in Toms River that were affected, they’d never been flooded before and the odds are, they’ll probably never be flooded again,” he said.

‘Gut-wrenching emotional decisions’

But perhaps the largest factor in these buyouts and a common cause for delays are all the emotions that come with leaving a longtime home.

Some families have requested to stay until the end of the school year, says Boornazian.

“There’s some people that come to us and say, ‘I want to die in this house,” he added. “It’s not all logical. It’s very gut-wrenching emotional decisions that people have to make.”

After all the work Zigmunt Dombrowski put into his house and the 49 years of memories he has there, he’s says he simply can’t move. He can’t imagine where he’d go.

“Why would I want to leave now?” he asked. “When we came here there were only two or three houses. If they all leave, that’s fine with me. I’m used to that. That’s the way it was before.”

Dombrowski says even if the state offered him more money, he still wouldn’t sell.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.