Under new directive, Pa. Dept. of Health dismissed 92 percent of Philly nursing home complaints

Photo via ShutterStock) " title="ssgeriatriccarex1200" width="1" height="1"/>

Photo via ShutterStock) " title="ssgeriatriccarex1200" width="1" height="1"/>

(Photo via ShutterStock)

Between 2012 and 2014, complaints of abuse or neglect filed against Philadelphia nursing homes had a 92 percent chance of being dismissed by the Pennsylvania Department of Health, according to a new report compiled by Community Legal Services. It also found DOH imposed far fewer monetary penalties during that time on nursing homes.

CLS has manually sifted through two years-worth of dense DOH nursing home investigation reports in an effort to get a comprehensive look at how many complaints were substantiated in Philadelphia nursing homes. The analysis concludes that of the 507 complaints filed against the city’s 46 nursing homes, only 43 investigations were substantiated by DOH.

In other words, only 8 percent of investigations prompted by complaints yielded a violation. Additionally, none of the required follow-up surveys in that period found violations to be persistent.

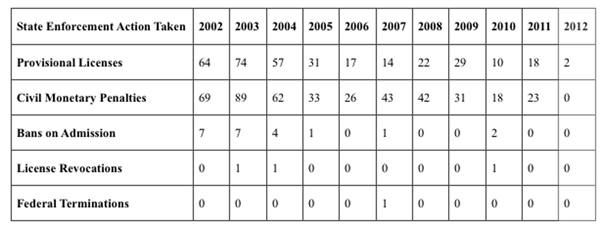

Enforcement actions have dropped dramatically in recent years, as illustrated by DOH’s own website. Civil monetary penalties (fines) decreased from an average of 44 per year from 2002 to 2011 to an average 8 from 2012 to 2014. Other enforcement actions, including downgrading facilities’ licenses to provisional and imposing bans on new admissions, had similarly steep declines. (Chart courtesy of Community Legal Services)

Enforcement actions have dropped dramatically in recent years, as illustrated by DOH’s own website. Civil monetary penalties (fines) decreased from an average of 44 per year from 2002 to 2011 to an average 8 from 2012 to 2014. Other enforcement actions, including downgrading facilities’ licenses to provisional and imposing bans on new admissions, had similarly steep declines. (Chart courtesy of Community Legal Services)

DOH is required by state and federal laws to complete annual inspections, investigate complaints and impose enforcements on facilities that fail to comply with regulations. Nursing homes are also required to report certain incidents, including negligent deaths, falls and patient elopements.

However, a state bulletin bearing DOH’s letterhead suggests the department began adopting a loose interpretation of those regulations in November of 2012.

Lower standards

Distributed to nursing home administrators across the state, the bulletin encourages facilities to refrain from reporting specific events to DOH. These events include medication errors and adverse reactions to medication, falls with injuries, inappropriate discharges and “misadventure with feeding tube, catheter, tracheotomy or life sustaining equipment.”

These are events that, needless to say, jeopardize the health and lives of nursing home residents. But according to state code, events of this caliber dwell in legal gray area. According to CLS, DOH claimed that Pennsylvania regulations do not pertain to specific incidents such as “falls with injuries,” “misadventure with life sustaining equipment” and “medication errors/adverse drug reactions causing serious injury.”

When such hazardous incidents are observed during annual DOH surveys or complaint investigations, they are grounds for violation. But if the extent of their harm is being played down, that might explain why 92 percent of complaints in Philadelphia are deemed unfounded.

If DOH is dismissing the vast majority of nursing home complaints in Philadelphia, are they treating complaints similarly in other counties?

Back in February of this year, Julie Lisiewski filed a complaint against Emmanuel Center for Nursing Rehab in Danville, Pennsylvania, for failing to detect her mother’s urinary tract infection on several occasions. The facility is in Montour County in the middle of the state. Though undetected infections are often a sign of neglect, the investigation was deemed unsubstantiated. It was not the first time Lisiewski had filed a complaint — she’s filed on at least four separate occasions at three different homes since 2011.

One month later, Lisiewski’s mother was diagnosed with sepsis. The illness, Lisiewski said, was triggered by an undetected UTI. After suffering from a reaction to medication, Lisiewski’s mother passed away.

The reaction to the medication was not reported. Lisiewski filed her last complaint one month after her mother passed. It was ruled unsubstantiated.

“When we make a complaint to the Department of Health, nothing happens,” said Lisiewski. “It’s over. It’s done. It’s dead. I can’t go back and say ‘You didn’t investigate this properly.’”

Downgrading injuries; downgrading penalties

By law, each violation must be assigned a characterization during the DOH survey. Each level of harm is designed to classify the severity and breadth of harm done to residents. These characterizations can range from low-risk “potential for minimal harm” to high-risk “severe harm.”

According to the CLS report, the DOH routinely minimizes these characterizations, which is evident in their review Philadelphia’s nursing home surveys. Between 2012 and 2014, DOH never classified a negligent death as severe harm in Philadelphia. Yet, a handful of negligent resident deaths within that same timeframe were classified as either minimal or actual harm.

CLS’ review of violation data includes the following instances of minimal harm, defined by DOH as causing “minimal discomfort to the resident”:

A resident who set her head on fire at Inglis House (minimal harm, Jan. 27, 2012).

A nurse at Oakwood Healthcare and Rehab who forged a prescription for morphine and stole it from the patient. The nurse then administered the drug to another patient, who was then hospitalized (minimal harm, March 18, 2013).

A patient who required hospitalization after being dropped on his/her head by staff at Deer Meadows (minimal harm, Oct. 21, 2014).

The failure of Tucker House nursing home staff to provide emergency care to a non-responsive patient, who subsequently died (minimal harm, Jan. 20, 2012).

Depending on the severity of harm, DOH can impose penalties in a few different ways: staff re-trainings, monetary penalties and, in drastic situations, shut down a facility. By downgrading levels of harm, DOH also downgrades the penalties available to impose on nursing homes.

On a statewide level, DOH issued an average of eight monetary penalties per year against nursing homes under the Corbett administration from 2012 to 2014, though in 2012 DOH issued no monetary penalties at all. That’s a significant decrease when compared to data from 2005 to 2011, when there were frequently between 30 and 44 monetary penalties issued per year.

NewsWorks wanted to offer Michael Wolf, who ran the Pennsylvania Department of Health under former Gov. Tom Corbett, a chance to respond to these figures. However we were unable to locate his new place of work since leaving office in January. Two messages left at a home phone number believed to be Wolf’s went unreturned. We also attempted to contact him through social media but did not hear back.

Unreliable data for families, the public

Mischaracterizations of harm don’t just interfere with the appropriate enforcements and risk residents’ health and livelihood. They stymie those who want to monitor enforcement. For families searching for a prospective facility, it is far harder to get an accurate understanding of a nursing home’s track record.

All that DOH survey data — whether gathered from an annual survey, complaint investigation, follow-up investigation or self-reported event — is required by federal law to be submitted to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). CMS then plugs all of that information into their public Nursing Home Compare tool.

But families can’t make sound decisions based on unreliable data.

For example, from 2012 to the present, CLS reports 38 complaints have been filed against Care Pavilion on Walnut Street — the most of any nursing home in Philadelphia. Granted, Care Pavilion is also the largest nursing home in the city with 400 beds. That’s nearly four times as many beds as other homes in the city, according to owner Dr. Scott Rifkin, who also said the facility has been a five star-rated building for most of the past three years.

“Care Pavilion is one of the best facilities in the city,” Rifkin said. “The number of complaints has been lower than the community average if you adjust for the size of the building. Furthermore, none of those complaints turned out to be substantiated when the state came out and looked at them, as they do routinely.”

According to CLS, all but one complaint against Care Pavilion were dismissed by DOH. During that same period of time, the nursing home itself reported the death of an unsupervised patient who choked on a mustard packet and a dementia patient leaving unnoticed.

Neither of the two self-reported events were characterized as severe harm (despite both being caused by lack of supervision), so neither immediately show up on the CMS site. Neither do any of the dismissed complaints from the past three years. Yet, the Care Pavilion is still listed on the site as having an above average rating for quality measures.

“One of the major consequences of the Department of Health’s failure to properly investigate complaints and to enforce regulations is that the public becomes misinformed,” said Sam Brooks, a staff attorney at CLS and lead on this report. “The public relies on the Department of health to go out into nursing homes and to evaluate how safe they are, how clean they are, how well treated the patients are. When the Department of Health is not doing that, the public cannot make an informed decision about where to place themselves or loved ones.”

CLS says systemically reforming the way DOH manages public data, investigates abuse complaints, characterizes violations and makes the appropriate enforcements is crucial to the wellbeing of Pennsylvania’s elderly community — as well as the state’ss elderly-to-be. Could that reform come from the Wolf administration?

“These regulatory activities occurred during the previous administration,” said DOH Secretary Dr. Karen Murphy in a statement. “We are committed to ensuring that all facilities licensed and certified by the department meet state and federal quality and safety standards. The department evaluates every complaint brought to the department’s attention and follows up if indicated for evidence of compliance with state and federal regulations.”

“My concern is, what’s going to happen to our next generation? Will we be victims of the same fate?” asked Lisiewski. “I’d rather be dead than experience what my mom experienced, because she experienced elder abuse, and they got away with it. They got away with murder.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.