Trying to overcome “undermatching” in Delaware

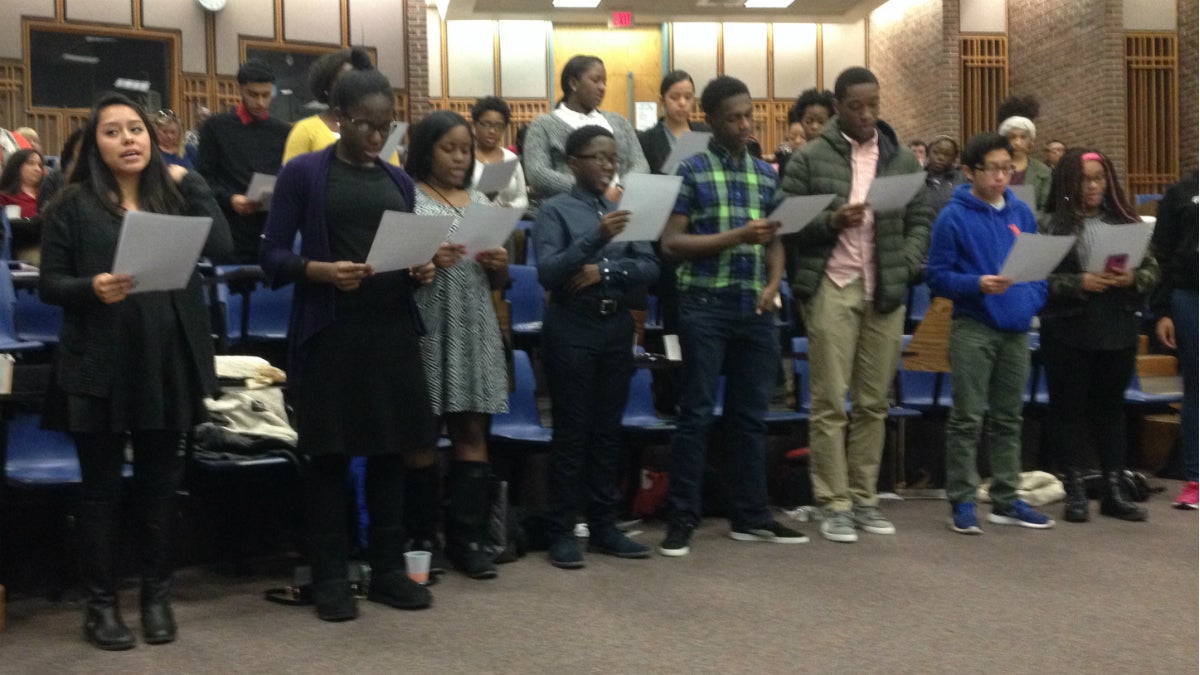

TeenSHARP's Delaware contingent is sworn in at a Saturday ceremony. (Avi Wolfman-Arent, Newsworks/WHYY)

How can Delaware place more high-achieving minority students in prestigious colleges? One new program thinks it has the answer.

It started with a pledge.

On Saturday morning in a lecture hall on the campus of the University of Delaware, 30 teenagers vowed to spend the rest of their high school careers in relentless pursuit of excellence. Standing together and chanting in unison, they promised to sacrifice weekends, sleep, and a good chunk of their glory years in hopes of gaining admission to one of America’s top colleges.

“We will be strivers,” they said as friends and families looked on.

“We will be appliers…”

“We will be connecters…”

“We will be starters…”

So concluded the induction ceremony for TeenSHARP, an immersive tutoring and mentorship program that feels like an after-school club set into hyper-drive.

Founded in Camden, New Jersey in 2009, TeenSHARP’s goal is to make sure the high-achieving minority students in its charge make good on their potential. And toward that end, it is designed to ensure they don’t end up like many of their peers–languishing in mid-tier colleges that belie their intellectual gifts.

Undermatched and under pressure

Over the last decade, “undermatching” has become perhaps the buzziest buzzword in higher education.

Based largely on the work of Stanford economist Caroline Hoxby, undermatching describes the tendency for high-achieving, low-income students to choose middling colleges with middling retention rates over selective schools with stellar graduation rates.

The reasons for this phenomenon are multiple. Low-income stuents may not think they can cover tuition at a highly selective private college, confusing sticker price with affordability. They may not believe themselves worthy of admission. They may not know such schools even exist, choosing instead more familiar local universities.

No matter the reason, the results can be devastating. Promising low-income students may end up paying more out of pocket to attend a school that lacks resources, supports, and the career benefits attached to a degree from a well-respected college.

TeenSHARP tries to combat undermatching by latching on to a handful of promising students of color early in their high school careers and pushing them to excel. TeenSHARP participants must apply for all manner of internships, fellowships, and career opportunities. They must conduct community projects at their schools and fill leadership roles. And above all, they must go to TeenSHARP meetings every Saturday that last from 10 in the morning to about 4:30 in the afternoon.

Essentially they have to do an extra day of school from the time they enter the program–typically in 9th grade–until the time they graduate high school. During TeenSHARP Saturdays they receive tutoring, counseling, and learn the ins and outs of the college application process. They are spurred to do more and reach higher.

“You’re looking for a very particular type of kid who says ‘this is an investment I’m exited to make and look forward to making,'” said Tatiana Poladko, TeenSHARP’s executive director.

A bleak situation

Poladko and her husband, Atnre Alleyne–who works for the Delaware Department of Education–founded the program after making a new year’s resolution to be more involved in the educational success of Alleyne’s niece. From that vow to help one child, they dreamed up the idea for TeenSHARP and launched the Camden, New Jersey campus. So far, according to Poladko, about 90 percent of TeenSHARP graduates in Camden now attend one of the nation’s 187 most selective colleges (as defined by the financial magazine Barron’s).

Delaware is TeenSHARP’s second campus, and Poladko says the First State is in particular need of this program.

Of the Wilmington-area high school seniors deemed “highly qualified” for college–meaning those that scored 1550 on the SAT or higher–just 14 percent attended one of the America’s most selective schools. That’s according to an analysis done by the Center for Education Policy Research and provided by TeenSHARP. The numbers are even worse for African American students (11 percent) and students eligible for free or reduced lunch (9 percent).

“The situation is pretty bleak,” said Poladko.

Poladko concedes that the type of students accepted into TeenSHARP are likely headed to college anyway. The purpose of the program is to make sure they go to top schools. And to make sure they become “college ambassadors” at their respective high schools, acting as guides for other promising students.

Hope ignited

On Saturday, the students assembled seemed eager to make that leap.

Alejandra Vilamares, a junior at Howard High School in Wilmington, spoke about her parents’ journey from Mexico and her father’s subsequent deportation when she was 12.

“I want to make my parents’ effort and courage count,” she said.

Jasmin Scott, a junior at POLYTECH High School in Woodside, excitedly rattled off a list of schools she’s eying: Princeton, Georgetown, Drexel, Penn.

Junior Catherine Ebron from William Penn High School in New Castle always figured she’d go to the University of Delaware. Now thinking diffrently.

“The first thing I realized when I joined TeenSHARP is how unprepared I was for college,” she said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.