To understand the migrant crisis, first we must listen

We hear these stories so rarely — and almost never in the asylum seekers’ own voices.

(Osmyn Oree)

Like many others, I have been deeply disturbed by the recent images from the U.S.-Mexico border. One of the most heart-rending shows a mother with two small children running away from a tear gas attack by U.S. authorities.

Just as disturbing to me was that during all the debate about the “caravan” and what it represents politically, I have heard so little in the media from the asylum seekers themselves.

What was that woman’s name?

What was her story?

Why had she come on such a dangerous journey with her two children?

We hear these stories so rarely — and almost never in the asylum seekers’ own voices.

I believe that their voices are powerful and need to be heard.

As an artist, I have made it my work to create spaces and forums where families can speak directly and share their stories on how they have been affected by these anti-immigrant attacks. For that reason, I created my “Familias Separadas” project, which sought to work with these families to amplify their own voices.

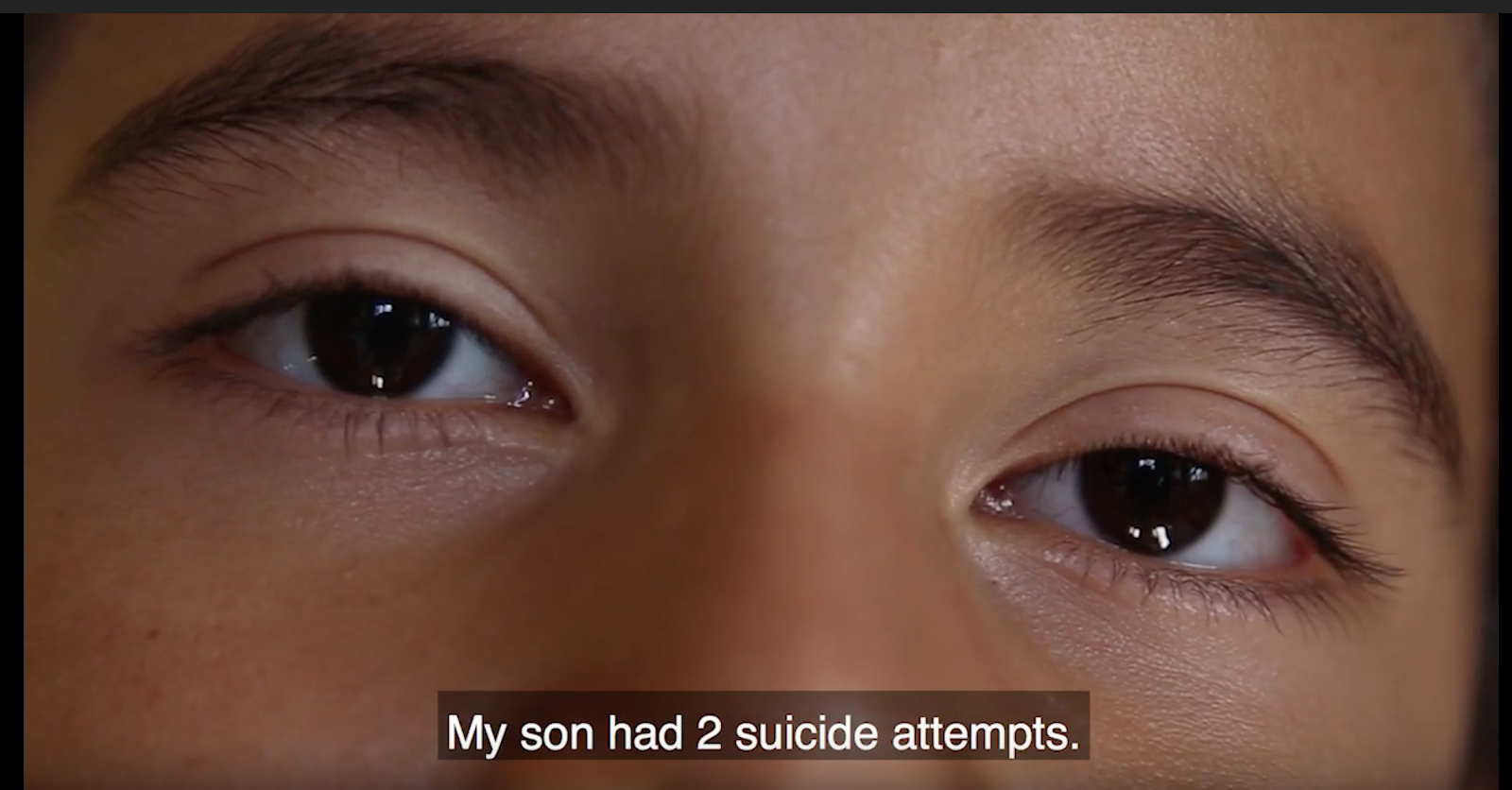

I recently unveiled several public art installations in Harrisburg. The Capitol steps were covered with an 88-foot mural with portraits of two pairs of eyes — the eyes of Karen and her son 6-year-old son, Steven, who were detained for 651 days at the Berks County Residential Center, a detention center in Pennsylvania.

“My son had two suicide attempts in Berks,” Karen told me in an interview. “With the string of his ID. He told me he was going to hang himself, throw himself out the window if he couldn’t leave …

“It doesn’t hurt me anymore, I think I’ve overcome most of it. But at the same time, you can’t really get over something like that. Seeing your son who’s only 6, 7 tell you — how did he know trying to kill himself was a possible solution?”

Karen was one of 14 mothers ncarcerated at Berks for nearly two years. The women, like the families seeking asylum at our borders, were fleeing from violence in El Salvador and Honduras.

After enduring two suicide attempts by her son during detention and organizing hunger and labor strikes with the others, Karen and 10 other mothers were sent back to El Salvador, forced to return to the violence they had fled.

Karen uses her real name, while the other four mothers featured in the “Familias Separadas” project use pseudonyms to protect their identity. Delmy, one of four mothers released from Berks in August 2017, is still fighting against her deportation and lives in fear of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Delmy, like the families seeking asylum at our borders, walked with her son through El Salvador, Guatemala, and Mexico. When she arrived with her son on U.S. soil, she was detained in Texas, then transferred to Berks where she and her son were held for 654 days.

Her eyes and message were enlarged to 40-foot billboards that meet you as you enter Harrisburg. Here is what she told me about the journey to the United States:

“I had to leave with my child immediately, it was very sudden. Coming to this country, leaving my own, it was very difficult because it’s a long journey. I had to cross three borders … We cried because of all the horrible news we got, but at the same time, we always kept going, always with our heads held high. I have a son, and I want him to have a future, I don’t want anything bad to happen to him back in my country. That’s what kept me going.”

My hope is what when people encounter these stories of detention and deportation through art, they are able to connect, empathize, and then channel that energy into action. At the same time, the project is meant to accomplish the opposite of journalism, which I believe too often treats these people as objects of debate. Instead, my project allows the families to tap into their own power so they can reveal themselves not as victims, but as full whole human beings who continue to fight for themselves and the love of their children.

The response to my project at the Capitol is, unfortunately, a good example of how these stories have been treated — and a direct result of the way immigrant families have been made into political objects. State Sen. Joe Scarnati, the Republican leader, instantly objected to the mural on the steps. He issued a statement demanding that the “political messaging” be taken down.

Why did Scarnati think it was political? Why did he think it was about him or his party? Why didn’t Scarnati, or even Gov. Tom Wolf, just ask, “Whose eyes are those? What is their story? Why are they in pain? What can we do to help?”

Scarnati deemed the artwork as “inappropriate” when he really should be ashamed of incarcerating children and their parents in our own state.

Listen directly to the voices of those who are being detained, who are being turned away, who are fleeing to provide safety for their children. Their stories of resilience and love are what need to be the driving force to the change that needs to happen in our country.

Michelle Angela Ortiz is an artist living in Philadelphia.

Listen to the stories of the mothers featured in the “Familias Separadas” project.

Learn more about the “Familias Separadas” project.

Learn ways to take action in ending family detention in Pennsylvania

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.