How, and when, to teach little kids about consent and their bodies

When children understand the parts of their bodies, and that they can set their own limits on touching, it can be a factor in recognizing sexual abuse.

Listen 04:19

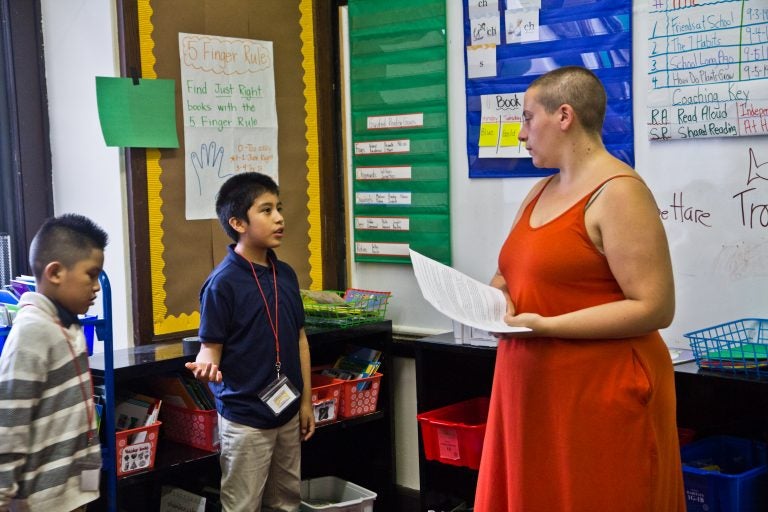

A third-grade student explains to Isy Abraham-Raveson about why he chose the green light on behavior during a consent workshop. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

How do we help children thrive and stay healthy in today’s world? Check out our Modern Kids series for more stories.

Isy Abraham-Raveson starts her “Yes to Consent” sex-education workshop by asking this question: What’s your favorite part of your body?

Hands eagerly shot into the air one recent afternoon, as a dozen third-graders — part of the health-and-wellness nonprofit Puentes de Salud’s after-school program — sat on a multicolored carpet square at the Southwark School at Ninth and Mifflin streets in South Philadelphia.

“My favorite part of my body is my brain because it helps me be smart,” one student said.

The question made for an easy segue into the kinds of touch the children like or don’t like.

“I love hugs from friends and family,” one boy said.

“I like to hold my best friend’s hand,” a girl replied.

After asking his permission, Abraham-Raveson tickled one of the boys.

A little silliness makes kids more comfortable talking about serious topics, she said — things like setting physical boundaries and understanding consent.

“I really encourage laughter, we play tons of games, we get really silly, and I think that’s all great.”

Some might be surprised to hear 7- and 8-year-olds are learning about bodily autonomy. In Abraham-Raveson’s opinion, the earlier the conversation starts, the better.

In part, that’s what inspired her, with co-founder Rebecca Klein, to create Yes to Consent, a four-year-old nonprofit that hosts sexuality education workshops for all ages across the northeastern United States. They’re now working on expanding and connecting with schools, to make up for a lack of sex ed and to help steer away from an abstinence-only mentality. At Southwark, they’re running a 12-week workshop.

In much of the country, sex education is not a standard part of the curriculum. Only 24 states and Washington, D.C., have mandated that public schools teach sex ed. Pennsylvania is not one of them.

Schools in Pennsylvania are required, however, to focus on abstinence from sex.

The commonwealth also requires schools to provide preventive education on sexually transmitted infections and HIV/AIDS. Teaching students about consent is not mentioned.

State Rep. Brian Sims, D-Philadelphia, has introduced a bill that would require school districts to integrate comprehensive sex ed into their curricula at all grade levels, teach contraception methods to older students, and mandate affirmative sexual consent at universities.

Understanding what consent is, and what it isn’t, is fundamental to an array of issues, such as public health, sexual harassment and sexual assault, as illustrated by the #MeToo movement. It is also considered a factor in preventing and recognizing child sexual abuse.

An estimated 1 in 10 children experience sexual abuse before they turn 18, according to 2013 research from nonprofit organization Darkness to Light. A 2015 data brief from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence survey says that 1 in 5 women and 1 in 14 men will be the victim of rape or attempted rape at some point in their lives.

Lori Reichel is a school health educator who most recently worked at the University of Wisconsin – La Crosse. In the past, her research has focused on how parents talk to their children about sexuality. In 2018, she wrote the book “Common Questions Children Ask About Puberty.”

In some ways, she said, talking about consent in elementary school is a form of assertiveness training.

“It’s telling them, ‘This is their body,’ and on one level, it’s common sense,” said Reichel, who is working with the Chicago public schools to revise their K-12 sexual health curriculum.

Specifically, she said, a child’s ability to name and identify their genitals and other body parts can be effective in recognizing and preventing sexual abuse. Studies have shown that children who lack sexual knowledge may be more vulnerable to abuse. Some sexual offenders avoid children who can anatomically name their genitals because it can suggest they’ve been educated about body safety and sexuality.

“If a child is inappropriately touched and they know how to verbalize it with the words, it can be heard in a court system better and the perpetrator can actually be held more accountable,” Reichel said.

Abraham-Raveson started Yes to Consent in 2015 by teaching sex ed in her hometown of Montclair, New Jersey. After earning a master’s degree in sexuality education from Widener University, she realized that the way she wanted to teach consent was quite different from the way she had learned about it.

For starters, she realized, teaching consent can’t be a one-time thing. To succeed and make a lasting impact, the workshop’s lessons would need to be incorporated into school curricula — and into kids’ interactions at home with adults such as parents, close relatives, and family friends.

Typically, she said, consent isn’t mentioned at all in sex ed curricula. The rare times that it is, she said, the focus is on “it’s OK to say no, here’s how you say no, here’s how to defend yourself.”

And often it’s a conversation broached only with high school or college students.

“It’s a new concept really late in the game for people, who we really should have been talking about this with since they were really small children,” Abraham-Raveson said. “And it’s children who have the least control over their bodies. So that’s a time when it’s really important to be talking to them about what their rights are, and how adults should and shouldn’t be touching them, how they should and shouldn’t be touching each other, and what feels good.”

Setting boundaries young

Lessons in consent need to start as early as possible — teaching preschool taught her that, Abraham-Raveson said.

“That’s the age when we kind of teach young people how to be citizens of the world.”

It’s the age when we teach our future leaders how to share toys — which isn’t a far-off concept from consent, she said. If one child is playing with a toy another child wants, they are taught to ask if they can play with the toy too — and not just grab it.

Why, she said, would our bodies be any different?

As kids grow into young adults, the message they receive is often mixed, she said: They’re taught at a young age to be kind and respectful people, but with their own bodies, it’s as if there’s a caveat.

“We’re saying that it’s normal for an adult to come pinch a kid’s cheeks they don’t know … or just reach down and pick up a child you’ve never met before, and kids are just supposed to kind of go with the flow on that,” Abraham-Raveson said. “So I think it makes complete sense to become explicit with young people and say, ‘Sometimes, adults do touch you without asking. How do you feel about that?’”

The Yes to Consent workshops aim to help kids unlearn certain ideas, like embracing a grown-up because that person brought you a present.

During the Puentes after-school workshop at Southwark, Abraham-Raveson turned a psychological experiment into a game.

On a classroom’s walls, she taped up red, yellow and green pieces of paper, then she told a story. If it sounds as if the character’s boundaries are being respected, she told the children, run to the green square — to signify the situation is OK. If it sounds like they’re not being respected, run to the red. And if you’re not sure, then head to the yellow paper.

In one scenario, Abraham-Raveson imagined a boy named Jorge tickling his younger cousins. The cousins are laughing, she said — and several of the students scurried to stand underneath the green and yellow papers.

But then, the cousins’ response to the tickling changes. “So the cousins are laughing and laughing, and then the cousins are yelling, ‘Stop, stop!’” Abraham-Raveson said.

With that, many of the kids hunkered underneath the red paper.

“Now why are you at red?” Abraham-Raveson asked one boy.

“Because I heard them say, `Stop,’” he replied.

Helping children identify their own bodily boundaries, and how to respect those of others, is the lesson here. It’s something that might help them as they grow into adults.

While crafting workshops for a school or community organization, Abraham-Raveson tailors the program to fit the students’ ages. Ideally, she said, she’s able to produce a multi-week series that covers topics ranging from consent to gender identity.

Her team has done workshops at public and private schools in New Jersey and Philadelphia, at community centers, at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and at Parent Infant Center, a West Philly preschool where she taught for three years.

The youngest kids she has done workshops with are 3-year-olds.

With the littlest ones, the Yes workshop is usually a basic intro to bodily autonomy. Abraham-Raveson asks them: “How do you like your body to be touched?”

The children may say things like, “I like when my mommy rubs my head.” Then she may prompt them and ask, “Do you like when everyone rubs your head?” To which they may affirm something like, “No, only my mommy.”

Similarly, Abraham-Raveson gets them thinking about how to read someone’s body or facial language to gauge their comfort level, asking questions like, “What does your face look like when you are being touched? What does your face look like when you don’t like it?”

Helping parents unlearn their sex ed (or lack thereof)

Abraham-Raveson has also hosted workshops for adults. For some, it’s a way of reckoning with their own childhood experiences and how their parents talked about consent and sexuality.

She starts with a partner activity in which the parents or caregivers discuss the messages around sexuality they received as kids, what they wish had been different, and the overall long-term effects.

Mary Maier, who has a 10-year-old son and a 7-year-old daughter, attended a workshop at the Parent Infant Center, where Abraham-Raveson formerly taught her daughter, Alison. She said a lot of what they talked about in the workshop was incorporated into Alison’s classroom.

Even though Maier grew up in a “progressive and liberal” household, she said she was surprised at what she learned in the workshop.

For her and her husband, it was a lightbulb moment.

“Even both of us remember as kids, your grandparents came over and you have to go hug your grandparents. It doesn’t matter if that’s not what you want to do,” Maier said. “In the workshop, we learned that there are ways to incorporate knowledge of development and sexuality, and this really incredibly powerful idea of consent, even before kids are totally verbal.”

She now sees that ownership of their bodies in Alison and son Aiden — something she said she doesn’t think she or her husband had at that age. It’s about setting the foundation for what’s to come, almost like reading, she said.

“We don’t start with handing them a book. We start with letters and small parts, and you build on that knowledge,” Maier said. “And I just wish that was happening for kids everywhere.”

Imparting other important lessons

Yet some experts in the field think consent might be too individualistic a concept to teach young children as they learn to be responsive to their peers’ boundaries and emotions.

“To reduce what’s happening, and why there’s so many #MeToos, to a problem of people not knowing how to give consent is simplistic,” said Sharon Lamb, a counseling and school psychology professor at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. “It’s about gender and power and male entitlement, from a feminist perspective. To teach it in that way takes out that whole component.”

The implication, Lamb said, is that if we teach kids about consent, people won’t exploit one another, and she doesn’t “believe that for one minute.”

“I think if we teach people about respect and caring, then they are less likely [to exploit] … And that you do have to start really young with that, and a lot of schools are doing that,” Lamb said.

Consent, she said, is social and emotional learning that goes beyond those lessons.

“We know that people consent to things that are harmful to them, that there are oppressive environments, and situations where power is unequal, where consent isn’t enough,” Lamb said.

That’s why Abraham-Raveson sees recognizing the power adults have over our youngest citizens as crucial.

“Children are some of the most powerless in our culture,” she said. “We just really need to be mindful of how we use that power we have with children in order to create really empowered, and brave, and awesome kids who love themselves.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.