Tickets for trashy sidewalks are up 300%. It hasn’t fixed Philly’s litter problem.

More than half the violation notices issued by the city end up in the rubbish pile.

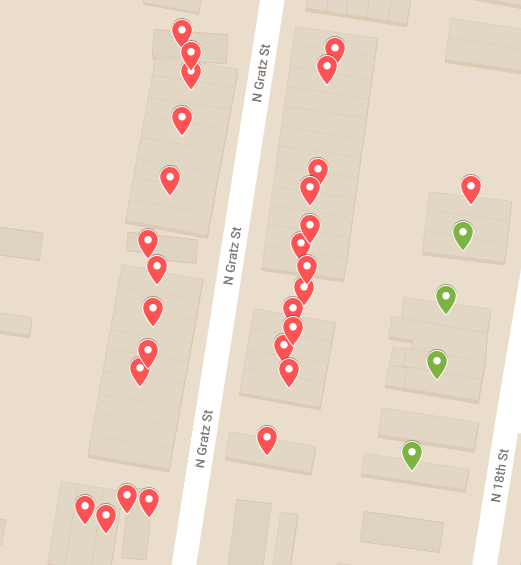

The 1900 block of North Gratz Street in North Philadelphia, home of the most ticketed sidewalks in the city (Max Marin/Billy Penn)

This article originally appeared on BillyPenn.

—

Just hours after trash pickup every week, the student-heavy residential blocks west of Temple University get hit by a small army of litter cops.

Robert Pollock, a 21-year-old Temple student who lives on North Gratz Street, admits his block isn’t the cleanest. On a recent morning, takeout containers, crushed beer cans and a lost page from a Marketing 101 book were strewn across the block. But he says he’s watched city ticket officers cite properties for even tiny pieces of litter, sometimes left behind by the department’s own sanitation crews.

“I think the students don’t take care of it,” Pollock said, “and I think the trashmen don’t take care of it.”

Jonathan Smith, a line cook who lives a few doors down, said he never saw the litter patrol in Philly before moving to North Gratz six months ago. Now he sees them all the time. “It’s not spotless,” he said of his new home, “but there are way messier blocks.”

While the Streets Department says ticketing on trash collection day is a standard practice citywide, residents observe that, week after week, the city’s fleet of litter police plays what seems to be an unfair game, singling out this block from many in an infamously litter-filled city.

A Billy Penn analysis of trash violation notices supports that observation. Out of half a million addresses in Philadelphia, just 105 properties were issued more than 20 citations between 2014 and 2018 — and about a quarter of them are on narrow North Gratz.

Across the city, most properties received no more than a single sanitation ticket for failing to clean up the trash outside. One property on North Gratz topped the list with 42 tickets for trashy sidewalks.

Such tickets are on the rise across the city, increasing nearly 300% over the last decade. Overall, the number of litter citations went from over 7,000 tickets in 2009 to about 20,000 last year, according to Billy Penn’s analysis.

Philadelphia is the last major U.S. without citywide street sweeping, despite a stumbling pilot program. Instead, code enforcement has been one of the city’s alternative weapons in its war on trash.

But critics say the ticketing program is a futile effort that does little to dam the rivers of garbage flowing through Philadelphia streets.

Despite the considerable energy spent on enforcement, the city’s own litter index indicates the North Gratz block actually got filthier between 2017 and 2018. And it’s not just Temple students who seem nonplussed by the tickets. About two-thirds of the blocks with super-high ticket counts got dirtier or showed no signs of improvement, according to a Billy Penn analysis of the city’s litter index, while about a third improved.

Targeting property owners doesn’t address the issue of people intentionally littering on the streets, property owners argue. The fines are instead passed back and forth between landlords and tenants — or simply ignored.

Only 45% of code violation tickets for litter on the sidewalk have been paid in the last five years — and as with all code violation notices, consequences for lack of payment are slim to none.

The city says officers target the blocks around Temple because of the number of complaints, the housing density and the amount of foot traffic. The area where North Gratz is located racked up more litter tickets than all of Center City combined. Some say it’s political pressure from Council President Darrell Clarke, who represents that district, though his office said it had “no knowledge” of any such efforts.

Litter tickets become ‘part of the litter pile’

About 50 litter officers work under the Streets & Walkways Education and Enforcement Program, better known as SWEEP. The 25-year-old initiative within the Streets Department is meant to educate residents about good litter practices — and penalize offenders with $25 to $200 fines.

Litter ticketing was a thing years before Mayor Jim Kenney took office. But the practice has steadily increased under his administration’s watch. Tickets for litter on the sidewalk are now the number one code violation in the city.

Lauren Vidas, an attorney and former member of Mayor Jim Kenney’s Zero Litter and Waste Cabinet, launched an unsuccessful bid for City Council this year with a focus on trash. She believes the SWEEP program needs a complete overhaul because officers target property addresses rather than individuals.

“You’re not going to deter the behavior if the people who are doing that behavior aren’t ultimately receiving the ticket,” Vidas said. “And frankly, even when people do get the tickets, they’re not paying the tickets. So, there’s absolutely no negative consequence.”

Pollock, the Temple student, said his landlord passed the tickets onto him and his roommates to pay up. He took the bundle of tickets to court, where he said the judge was frustrated to see a tenant rather than the property owner. His appealed tickets were dismissed, Pollock said.

There’s little pressure on either property owners or tenants to comply. In the rare event the city takes a litter violation case to court for nonpayment, property owners often wait to sell the property instead of paying, at which point the city collects its dues.

Property owners are also free to go about their daily real estate business. The Department of Licensing and Inspections still issues permits to individuals or companies with outstanding code violation tickets, a spokesperson said.

On the streets, SWEEP officers can issue tickets to individuals caught in the act of littering, but the data shows these are a small fraction compared to the number of tickets stuffed in mailboxes for trash on the sidewalk out front.

Asked if the city had any evidence this ticketing has impact, Streets Department spokesperson Crystal Jacobs said the biggest results were seen in recycling offenses.

“Both warnings and fines produce results,” Jacobs said.

Vidas said the code violations themselves end up contributing to the problem they’re supposed to be policing.

“I can count on two hands,” Vidas said, “the number of tickets I’ve had to pick up that have become part of the litter pile.”

‘There’s a lot of political pressure’

Jacobs, of the Streets Dept., said the volume of tickets in any given neighborhood is reflective of the complaints or issues raised by residents.

The 22nd Police District in North Philly, which encompasses the heavily ticketed blocks near Temple, saw a harsher crackdown than any other district — nearly four times the number of tickets issued across all of Center City, river to river.

But the city says this is normal.

“The percentage of tickets written in this particular area is a reflection of the area being densely populated, and having greater numbers of multi-family dwellings and student housing,” Jacobs said. “Also present are higher counts of foot-traffic, presumably yielding more litter.”

A spokesperson for Kenney said enforcement priorities can also be set by the mayor or members of City Council. Some say Council President Darrell Clarke’s office has put considerable pressure to ramp up enforcement in the Temple area.

“There’s a lot of political pressure in that area from the councilman’s office to do something about the trash problem,” said Peter Crawford, a property manager who’s part of the Temple Area Property Association. “I’m not saying who’s right or who’s wrong. But there’s a lot of pressure in that area to do something.”

Clarke’s office said that, to their knowledge, the Council President had not instructed Streets to ramp up code enforcement.

Either way, the results have been mixed. Temple is now exploring its own special services district, similar to Center City and University City, that would take trash pickup into its own hands.

Crawford says more trash collection is the solution to mitigating the complaints, as the amount of trash generated will keep ending up in the streets.

“An effective approach would be to provide extra trash pickup services, to go to twice a week or to reintroduce street sweeping,” he said. “Landlords and tenants do not have trash trucks. They’re not in the business of waste-hauling.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.