This Philadelphia teacher sees children for who they are and ‘who they may become.’ She’s retiring after 47 years in the classroom.

Frances Wilson, known to all as Annie, started working for the School District of Philadelphia in 1974.

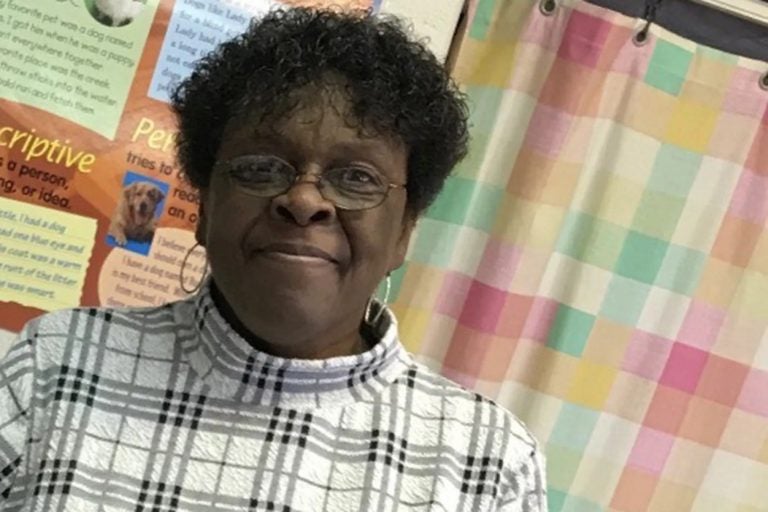

Frances Wilson will retire from Chester Arthur Elementary School next month after 47 years in the classroom for the School District of Philadelphia, first as an instructional aide and, for the past 13 years, as a teacher. (Courtesy of School District of Philadelphia)

This article originally appeared on Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

—

Frances Wilson, known to all as Annie, started working for the School District of Philadelphia in 1974. On June 15, she will retire from Chester Arthur Elementary School after 47 years in the classroom — first as an instructional aide and, for the past 13 years, as a teacher.

Hers was not the traditional path. She grew up in South Philadelphia and attended the now-defunct Durham Elementary School before finishing her elementary and middle years at McCall. For high school, she enrolled in the legendary Parkway Alpha program, the so-called “school without walls.” At Parkway, the city was the classroom. “We took classes at the Franklin Institute, the Museum of Natural Sciences, the Philadelphia Museum of Art,” she said. “We studied criminal law in City Hall, taught by an assistant district attorney. We got to meet judges.”

She received a scholarship to the University of Connecticut but soon came home and considered what she wanted to do next. In those days, she had zany career ambitions, noting: “I wanted to be general manager of a football team. I loved football. Or tour manager for a rock band.”

Her parents informed her passions. Her father was a jazz musician who was the longtime booker at the jazz bar Zanzibar Blue. Her mother had brothers who played baseball in the Negro leagues, and a sister, Ruth Arthur, who co-founded the city’s annual Odunde Festival.

At age 18, Wilson became an instructional aide at AMY, Alternative Middle Years, a new school located on Rittenhouse Square. But people were always telling her she’d make a great teacher.

“I just wasn’t sure I wanted to be a teacher. But I always helped children, all children,” said Wilson, who served as chair of the Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania’s children’s ministry committee, among other volunteer positions.

After more than 20 years as an aide, she decided to pursue her teaching credential. “I went into a classroom with children with autism. And I realized I could probably teach,” she said. She also noticed that there weren’t as many African American teachers in the district as she remembered from her own school days.

“At my elementary school, Durham, from first to fifth grade, my teachers were all Black women,” Wilson recalled. “The principal was a Black woman.”

Durham had been one of the segregated Black elementary schools the district operated for decades, a practice that only started to change in the 1940s. The purpose was to employ Black teachers to teach Black children only. When Wilson, 65, was there in the early 1960s, vestiges of that era were still apparent.

It took her a decade to earn her credential from Drexel University because she was working full time. She got her first teaching job in 2008 and has been at Arthur since 2013 — working with second, third, fifth, and sixth graders, sometimes specializing in math and science. This year she is the school’s dean of students, helping children and their families cope with everything from technology to emotional stress.

Arthur Principal Mary Libby said what she will miss most about Wilson is her sense of humor, her openness to possibilities, and “her ability to see people for who they are — not only who they are, but who they may become.”

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

As a teacher, what is the most important thing you can do for your students?

Come to understand who they are and build a relationship with the kid that’s in front of me, and realizing we all have different challenges and gifts, and looking at each child and trying to figure out what the challenges and what the gifts are. If something doesn’t work one day, come back with something else the next.

Do you wish you had become a teacher sooner, or are you happy with the arc your life has taken?

Sometimes, yes, sometimes, no. I wouldn’t be who I am if I hadn’t taken this journey the way I did. I don’t want to regret anything. I did what I wanted to do. When I went to UConn and came home, I could have gone right to college.

I still have a little gift certificate my mother wrote for me to go to Community College, which I didn’t use, but I still have it. I think I “done good’’ for myself. It is the ministry to children, the work I’ve done with children, that I don’t think I could have done without the experiences I’ve had throughout my life.

You call teaching a ministry. Could you talk about that a little bit more?

My faith as a part of the baptismal covenant is to see Christ in everyone, and that’s the way I approach kids. That’s the way I approach my parents. That’s the way I approach my colleagues. Some days, I’m very successful. Other days, I’ve got to rethink it and come at it again. I don’t give up, and I try to make sure everybody knows I have some respect for them, some enormous respect. But it’s still in progress, it’s still developing.

I’ve worked with kids with physical disabilities and some who need a lot of emotional support. I couldn’t do that if I didn’t see who they were and tried to figure out how I fit into their lives and what the gift was that they were giving me. It’s not always easy.

Have you heard from former students since announcing your retirement?

I’ve gotten a lot of contact with kids through social media. Some of their comments are overwhelming. This is from someone who is now a teacher. “Wow. I’m so happy for you. I can’t even imagine how many lives you’ve touched the way you’ve touched mine. I remember my days at AMY like yesterday, and you are a huge part of my memories. Enjoy retirement. You’ve earned it.”

These are my kids; they’re all adults now; some of them have grandkids. One of my former students contributed money to AMY in my honor.

What a way to spend your last year in education.

When COVID hit, it helped me to decide to retire this year. I was thinking about it for the last three years that I needed to step back and make myself a priority. I’ve always given to the schools I’ve worked at. At AMY, I was the eighth grade class supervisor. I helped write the roster. I was on the budget committee. I was always engaged after hours. Now, it was like, OK, time for you. I didn’t need to have children, I had enough in my life, a couple hundred every day, and they still remain my kids.

This year helped me realize I needed to spend whatever time I had left with my life on me. I’ll miss it, but I’m going to see what else is out there. I’m hoping that in 2022 I can go to Rome. It’s on my list. I want to learn a foreign language. I want to sit still and read a book. I want to honor my mom, who I haven’t had a chance to bury yet because of COVID, and I wish everybody could come. I’m going to spend some time doing nothing.

How do teachers captivate their students? Here, in a feature we call How I Teach, we ask great educators how they approach their jobs.

How do teachers captivate their students? Here, in a feature we call How I Teach, we ask great educators how they approach their jobs.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.