Things to know about lead in water

Ed. Note: Our environmental reporter, Catalina Jaramillo, investigated the Philadelphia Water Department’s efforts to notify residents about the risk of lead in their water supply. PlanPhilly compiled the information below for readers who want to know more about the issue.

Lead and Copper Rule (LCR): A federal rule published by the EPA in 1991 to control lead and copper in drinking water. It requires water systems to use treatment techniques and monitor drinking water at customer taps every three years, in at least 50 houses with lead plumbing. The rule requires the water utilities to take actions is the lead concentration exceed 15 parts per billion (ppb) or 1.3 ppm in case of copper, in more than 10% of the customers taps sampled. The rule is under current revision. “We have a regulation that is, I would submit, unjust,” said Virginia Tech’s Yanna Lambrinidou. “It leaves one party in the dark and vulnerable to exposures, blindly trusting the ability of water utilities to fully protect it from lead in drinking water, when in reality, water departments can never eliminate lead from leaching into the tap.”

Plumbum: The latin word for lead. From plumbum we get lead’s periodic symbol, Pb, and the English words ‘plumbing’ and ‘plumber.’ From ancient times until just a few decades ago, lead, a relatively common and easily malleable metal, was frequently used for water and sewer pipes.

Corrosion control: Chemical treatment to prevent pipe corrosion, which allows lead to leach into the water. Philadelphia Water Department uses zinc orthophosphate, which gives pipes a protective layer. Although this treatment minimizes the possibilities of lead coming into the system, it can’t completely prevent it.

Lead tests: Used to monitor if corrosion control methods are working effectively. The lead tests don’t measure if the tap water is safe, because it allows lead levels under 15 ppb. Researchers have also found out that the levels of lead vary from day to day, so tests should be done more than once to accurately determine lead levels. Philadelphia offers free lead tests for customers.

Concerns over lead tests in Philadelphia: An investigation by The Guardian published in June 2016 said Philadelphia had outdated lead-testing practices that “temporarily hide” lead contamination. The story stated that, in its 2014 testing, the Water Department asked customers to pre-flush the water or to let the water run so they can get the water from the main as opposed to water sitting in lead pipes; take the aerator out, a small filter at the top of the faucet; and tested in less than 50 high risk homes. Water commissioner Debra McCarthy told PlanPhilly it’s hard to get people to participate. They directly reached out to 263 people but only 68 samples were returned. Gary Burlingame, director of the department’s laboratories, said they’ve been doing sample regimes since 1992 and always followed federal regulations. “We chose not to follow the guidelines because it introduces variables and we were capturing the worse case,” Burlingame said. After pressure from the Guardian story, the Water Department started following regulation and tested again from July to December 2017. This summer the Water Department is testing again. This time they reached out to 300 properties and offer a $50 dollar bill credit to those who participate.

Shared responsibility: One of the things that surprise (and outrage) people the most is that they are partially responsible for drinking clean water at their taps. The Philadelphia Water Department claims they provide clean water, with lead levels accepted by federal regulation. But if you have higher lead levels in your tap, it’s your own pipes contaminating the water, therefore, you’re responsible for it. Activists say it should be a moral obligation for water utilities to communicate this to their customers. But the Lead and Copper Rule, the federal law that regulates lead in water since 1991, does not force them to do so. The Philadelphia Water Department said they communicate this in multiple ways.

Partial service line replacement: When the utility replace the portion from the water main to the curb, the valve. It has been found to be a major source of lead in drinking water. The recommended practice is to do a full line replacement, from the main to the water meter. The Philadelphia Water Department stopped doing partial replacements this year.

Philly Unleaded Project: A citizen-led project to independently test about a hundred houses in low income neighborhoods across Philadelphia. The local group included PennEnvironment and Drexel University, and the testing was done by Virginia Tech’s laboratory. Fortunately, all the samples of the Unleaded Project came lead-free. “I was dismayed and disgusted that the Philadelphia Water Department had very poor quality materials, some of them completely wrong, so we had to create our own” said Center for Hunger-Free Communities at Drexel University’s Mariana Chilton. The Water Department has since created new materials and increased its outreach efforts. PlanPhilly interviewed a handful of participants who said the experience opened their eyes and empowered them. “It wasn’t hard to make people care when you told then that this is something that you’re consuming that it could hurt you,” said volunteer Tianna Gaines-Turner. “Because of Flint, Michigan, a lot of people were skeptical about trusting water companies giving the correct information when it comes to trusting the water. Most people were very interested, eager to get their water tested and then calling us to ask if we’ve heard about it [results].” Members of local organization Witnesses to Hunger continue to work with parents in schools, training them and asking their children’s school to test their water.

Philadelphia Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Advisory Group: in December 2016 Mayor Jim Kenney released a plan to prevent lead poisoning in children and created this group to create recommendations. In June 2017 the final report was released. The goal is to reduce the number of children with blood lead levels greater than or equal to 5 micrograms per deciliter (μg/dL) by 40 percent, from 2,106 children in 2011 to 1,200 children in 2020.

FAQ about lead pipes for concerned residents

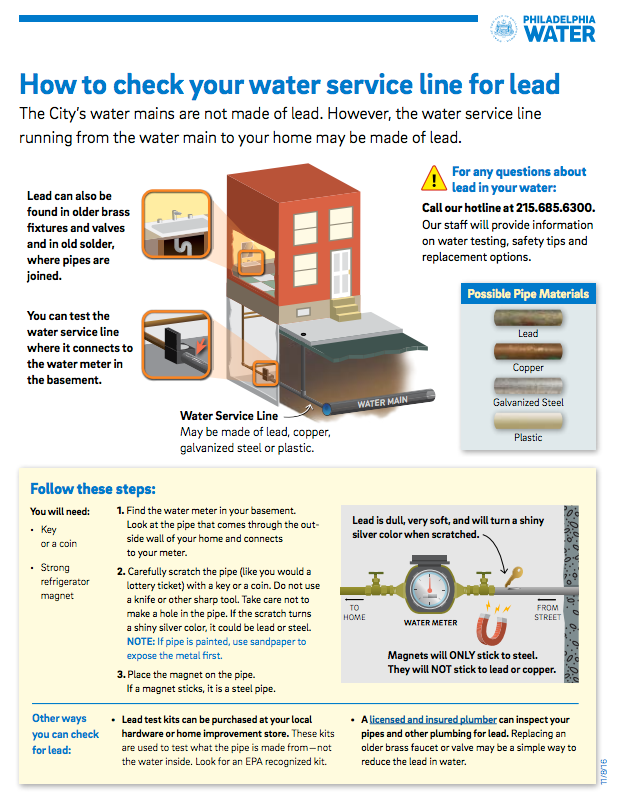

How do I know if I have lead plumbing?

Go to your basement and find the water meter. Use a coin or a key to scratch the pipe coming from the street into your house, to the water meter. If the pipe’s color is silver (if it’s red it’s copper), use a strong refrigerator magnet and see if it sticks. If it sticks, it’s steel. If it doesn’t is lead.

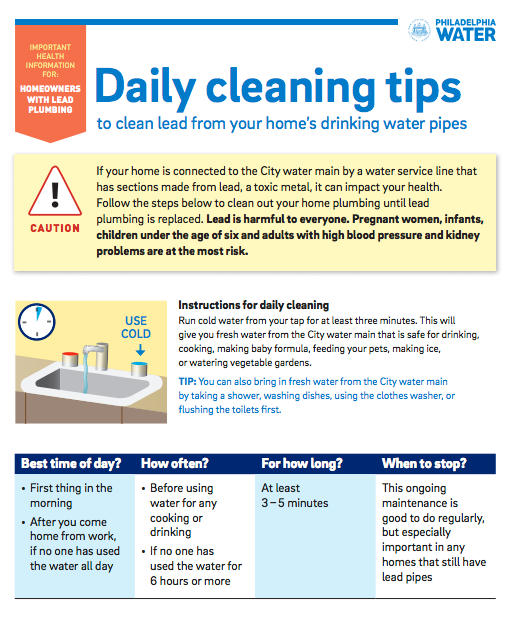

If I have lead plumbing, how can I protect my family?

If you can, your best bet is to replace the lead plumbing. This can cost between $3,000 and $8,000 and city residents may qualify for a no-interest loan to help finance the work.

If you let water sit in your lead pipes for over six hours, the chances of lead leaching in increases. So, the recommendation is to let your cold water run for three to five minutes every time you haven’t use the water for that long of a time. If you don’t want to waste water, you can do some laundry, water your plants, or take a shower (but only a cold shower). Always use cold water for drinking and cooking.

Replace your faucet aerator, a screen attached to the tip of the faucet, once a year, and clean it twice a year. To take it off, unscrew it and separate each part (aerator housing, aerator and rubber washer), soak them in white vinegar for a few minutes, scrub them with a toothbrush, and put them back together.

If there’s construction in your block or you replaced your service line or meter, the Water Department recommends an intensive flushing every two weeks for three months. To do that, remove all the aerators, run cold water from every tap in your whole house for at least 30 minutes.

Does boiling the water removes lead?

No. Boiling water will kill microorganisms in untreated water that can make you sick, but it won’t remove metal particles like lead.

Do all water filters remove lead?

Not all. Use filters certified by the National Sanitary Foundation (NSF).

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.