‘There’s no simple answer’: Can the whitening of Camden’s teachers be reversed?

A new report shows that since 1999, Camden teachers have gone from majority Black to majority White. WHYY explores the reasons for this trend.

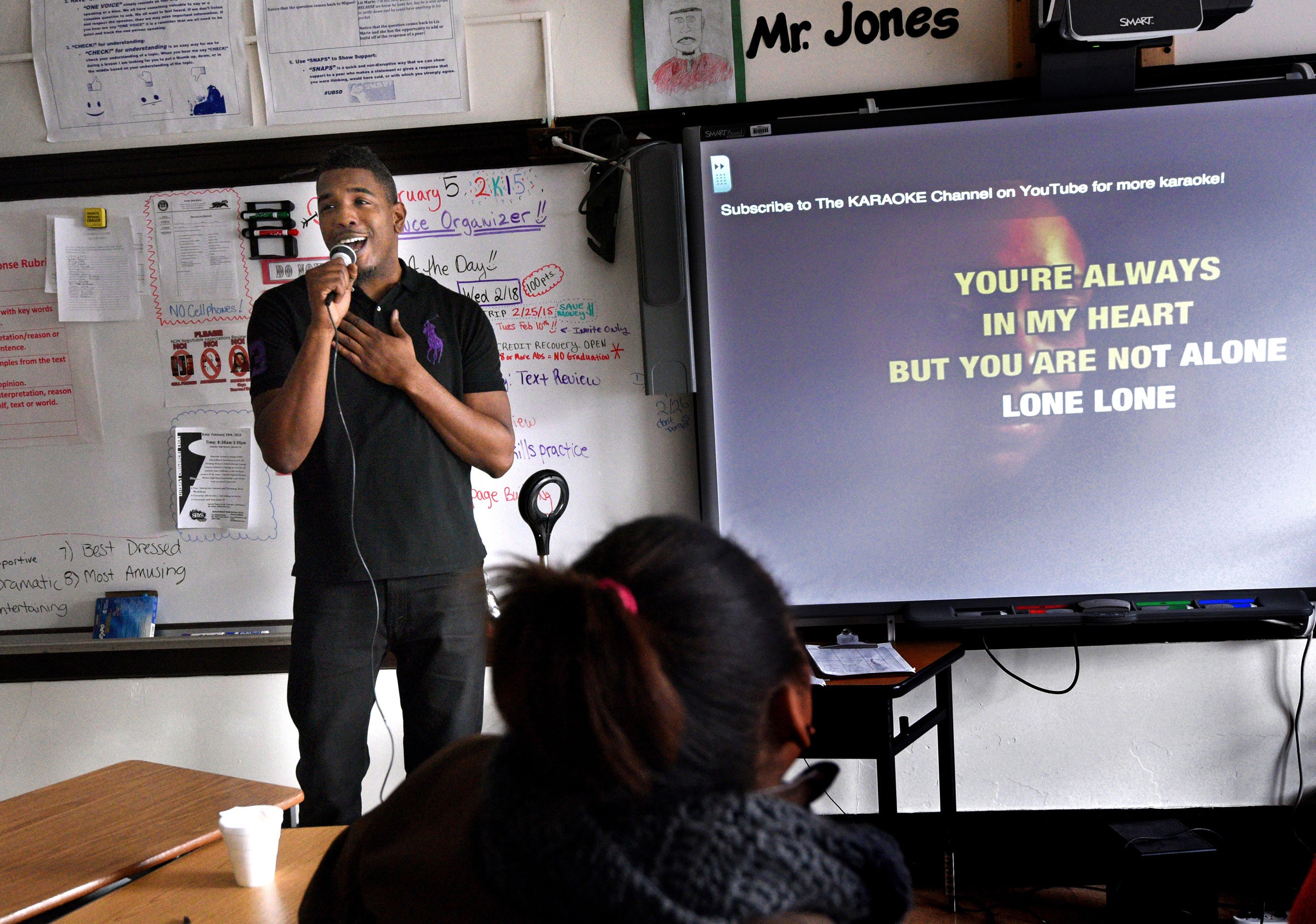

In 2015, Camden High teacher Alex Jones in the classroom on the day he tells his students he is leaving teaching to become an administrator. (Photo by April Saul for WHYY)

Alex Jones’ decision in 2012 to get a mohawk was hardly a casual one. The Black high school teacher in Camden, NJ was determined to “break the stereotypes of white supremacy culture” – starting with his hair.

“I got it because it was stylish,” said Jones, who also served as principal of Camden High School from 2016 to 2019, “but I kept it because I thought it made me more relatable to the students and cool.”

Jones, 39, admits the haircut shocked some families of his students of color – “I would have parents say to me, ‘What kind of principal wears a mohawk?’” – but the connection it fostered was priceless.

Rann Miller is a Black educator and Camden native who experienced a similar moment a few years ago, during a casual conversation about food with his teen students at LEAP Academy University Charter School.

“I told them, ‘The best store for chicken wings is the one at 7th and Vine!’” he recalled. “When they knew I knew Camden, it made a difference … and they could deal with me on another level. So my job became not to betray that trust.”

Jones and Miller are among only an estimated 2% of U.S. teachers who are Black men. A study published this month by the NJ Policy Perspective found that the percentage of Black teachers in Camden had fallen over the last two decades from 52% in 1999 to 30% in 2019.

In a majority Black and brown city – where the Camden County Police Department has made it a priority to hire more officers of color in recent years, including its first Latino police chief – the city’s students have fewer teachers who look like them.

Studies have shown that Black children who have even one Black teacher by third grade were 13% more likely to enroll in college—and those who’d had two were 32% more likely. Research also indicates that every 20% increase in a teacher’s expectations raised the chance of finishing college by 10% for Black students, who were given the strongest support from teachers of their own race.

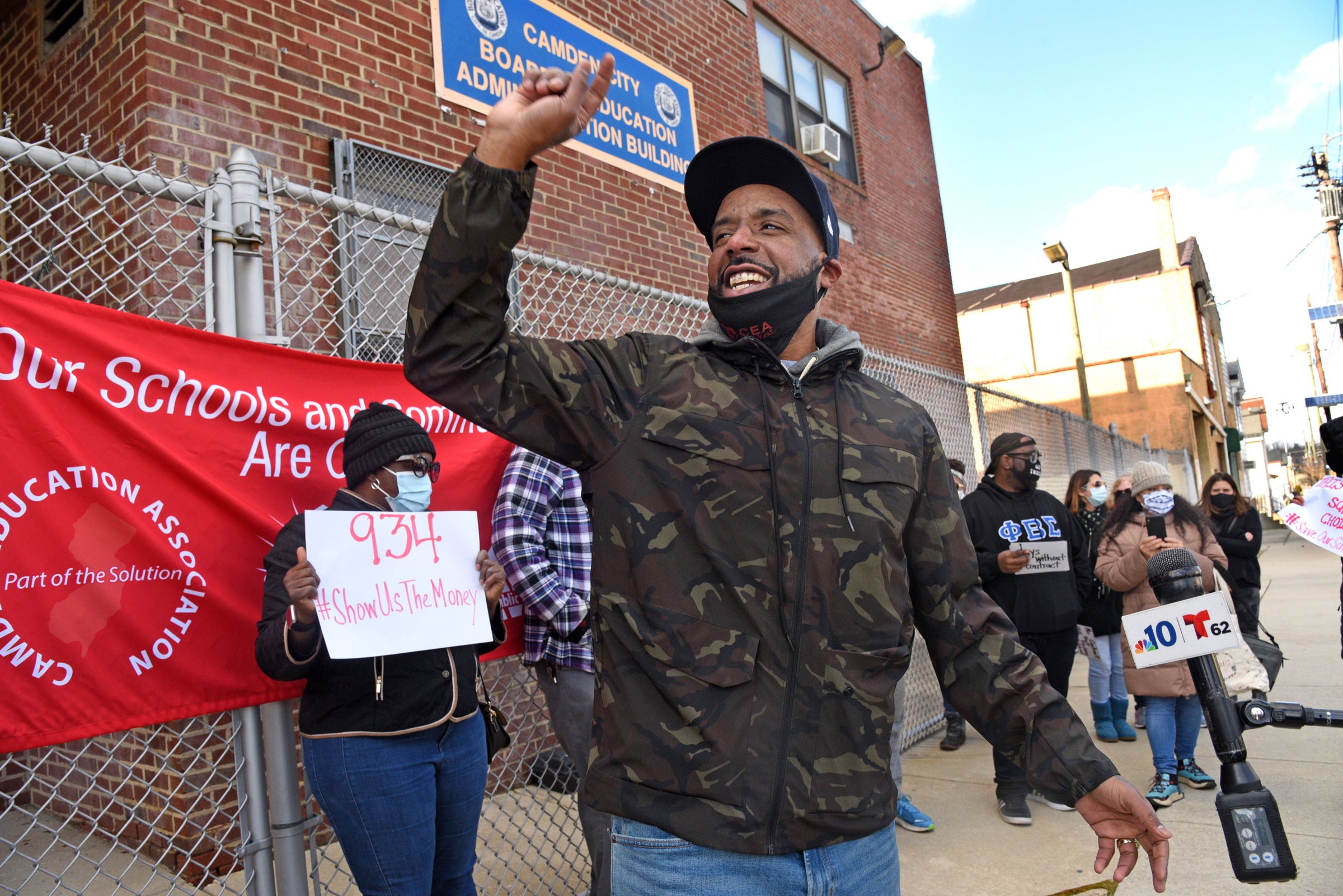

Camden Education Association president Keith Benson believes the steep drop is a result of the 2012 Urban Hope Act, which paved the way for a proliferation of charter and renaissance schools in the city; these schools are known for hiring fewer teachers of color than traditional public ones.

Benson said that a growing emphasis on test scores targeted the city’s public schools as being low-achieving and “rationalized the need for another kind of schooling” in the form of charter and renaissance schools. “And the people who were victimized by that,” he said, “were the older, minority teachers” at the traditional public schools, often let go when those schools closed to make room for the others. (In recent months, Camden school superintendent Katrina McCombs has announced her intention to shutter four more public schools. The proposed closures are currently under review by the NJ Department of Education).

Miller said young white teachers may also appeal to charters and renaissance schools because those institutions have their own educational philosophies. With new teachers, he said, “they can mold them, versus getting a veteran teacher, especially a Black one.”

Even more discouraging for Black educators, a 2019 Michigan study found that teachers of color there were 50% more likely to get a low evaluation as white ones, especially at schools with predominantly white faculties.

Theo Spencer, a former Camden board of education member, believes “there’s no simple answer.”

“The pipelines to Black educators that were there 20 years ago aren’t there anymore,” Spencer said. Back then, he said, many Black men and women were recruited to teach in Camden by giving them “emergency” teaching certificates – which are no longer available.

“They got rid of that,” said Spencer, “because they wanted people who had a stronger commitment to teaching.” He said today’s Black college graduates also have myriad more stable and lucrative choices.

“If the starting salary of teachers was $60 or $70k and there was loan forgiveness, you’d see a lot of Black people flocking to it.”

It’s the mission of Dr. Monika Shealey, Senior VP for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion at Rowan University, to make sure that some still do. Five years ago, her Project Impact program – which is designed to offer wraparound support for men of color who want to become teachers – began with 16 students. Participants are provided with scholarships, coaching for the Praxis test, hand-picked faculty members, and regular meetings with a group of mentors called the Men of Color network.

Last week, founder of the Philadelphia-based Center for Black Educator Development Sharif El-Mekki announced a $3.1 million initiative to increase the number of Black teachers in the U.S. The initiative focuses on the Black Teacher Pipeline, which has a goal of bringing 21,000 Black students into the Pipeline over 12 years, and supporting them with fellowships, apprenticeships and scholarships.

The reality, said Dr. Shealey, “is that our teacher education programs in America are 80% white women.” She would like to see a hiring process that predicts a candidate’s ability to teach a diverse group of students.

“We can determine if they have any racist ideologies. A test score isn’t going to tell you that.”

Benson has asked the Camden City School District to hold job fairs and reach out to HBCUs for Black candidates, and said that more Hispanic teachers are called for as well. “We need more teachers of color here, so you have to employ outside-the-box approaches,” Benson said.

Nancy Walker-Hunter, a Black health teacher at Camden High School, believes that while good teachers come in all colors, cultural understanding is imperative.

“In America,” said Walker-Hunter, “anybody can teach Black and brown children without knowing anything about their culture and that’s wrong … if I went to Japan to teach – or Guatemala, or Africa – they would not let me off that train, boat or plane to teach children in those countries until I was trained in the culture of the children I was going to teach.”

Miller recalls giving tours of Camden to new, white teachers during his tenure at LEAP. The first year, he said, “nobody got off the bus.” A year later, he organized a walking tour of North Camden that he felt yielded more insights.

“We opened a lot of eyes. “I really think it changed the perspective for some of these teachers.” Still, Miller stresses that “it’s not enough to just know the culture of the kids. You need to be able to put it into practice using real strategies.”

Walker-Hunter recalled leading a presentation to show other Camden teachers how to teach birth control. She said a white teacher commented that the students should be told not to have a baby until they were married.

“And I said, ‘What if you had students in your class who had parents who never married?’” said Walker-Hunter. “That was a cultural micro-aggression right there! You’ve just inserted your cultural bias into something that is quietly insulting someone in the room.”

A Camden High alumna whose uncle, Rev. Dr. Wyatt Walker, was a close associate of Martin Luther King, Walker-Hunter is often initially assumed by students to be white because of her light skin. When they realize she is Black, she said, “It’s often an immediate sigh of relief because then they know I’m from the same race, the same city, the same school, the same culture.

“I don’t have to prove myself as much as a white teacher might have to.”

Karen Borelli-Luke, who is white and has taught in Camden for nearly 40 years, believes “if kids are in a nurturing environment, they don’t see the color.” A Cherry Hill native, Borelli-Luke became known for rescuing animals during her early teaching years at Davis Elementary School.

The correlation between animal abuse and domestic violence dawned on her the day a young girl came to her in tears holding an abused puppy. “She said,” recalled Borelli-Luke, “’I was just hoping you could take me home, too.’ When you take the target of the abuse out,” she said, “the new target becomes the children.”

Her students at Davis, and now at Brimm Medical Arts High School – where Borelli-Luke helps lead Chowhound House, a nonprofit founded by Brimm students that helps struggling families care for their pets – quickly learned, she said, that “I’m going to do whatever in my power to be a voice for the voiceless.” She has also been a foster parent to several of her students.

Borelli-Luke also runs a program at Brimm called “Exposures,” which brings in alumni of color who have been successful in the health care field so that students “can see that they can do this.”

Ironically, Black male teachers in Camden are often promoted out of the classroom into administration because they are seen as being effective disciplinarians.

“Folks looked at me and said because he’s a Black guy, the students are listening to him. But it’s not that simple,” said Miller. “I was able to relate because I knew the city and I also treated them with respect.”

Miller kept teaching, but as many other Black male teachers are put in positions of authority to deal with behaviorally challenged students, said Shealey, “it leaves these gaps in the classroom.”

Jones was quickly promoted out of his classroom and into management roles. He cried with his students when he left Camden to work for Teach for America Philadelphia. He is currently Senior Managing Director of Program there and tries to bring in as many candidates of color as he can.

Jones doesn’t underestimate what he calls “The Wakanda Effect, where you had people of color who felt motivated and invigorated by seeing positive images of Black people on the movie screen.”

Still, he believes that for educators, “it’s more of a mindset thing than an identity thing. We are always pushing the mindset of teachers – Black and white – to believe that these children can achieve at the levels of their affluent peers.”

Miller’s most dispiriting experience was the year he spent teaching at a renaissance school that employed a controversial “no-excuses” philosophy. The theory behind no-excuse education is that academic gaps between low-income students students of color and more affluent ones can be bridged by employing rigorous teaching methods to achieve high test scores and strict behavioral regimes.

“If a kid had the wrong colored sneaker, they’d be sent to the main office where parents had to come and get them and bring the right ones. And there were situations where kids had to stand in a straight line and be quiet the whole time.”

Making things worse, said Miller, are racial disparities in discipline: while Black students make up 16% of New Jersey’s student population, they received 44% of suspensions during the 2013-14 school year.

“I went along with it for a while,” he said, “and then my spirit wouldn’t let me. I was told, ‘You’ve been letting the students get away with things, get them back in line, we want the old Mr. Miller back!’”

Miller stopped teaching in Camden and now directs a federally-funded, 21st-century community learning center in a N.J. school district.

“Black teachers can only do so much when all of these institutions are centered on whiteness,” Miller explained. “If you think Black teachers are going to come in and save the day, given the constraints put upon them by people who don’t understand how Black children ought to be educated, you’re wrong.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.