‘There are no answers’: One family pushes forward after losing teenager to suicide

Josh Sterner had good psychiatric care, a therapist and access to medication. None of that prevented his death.

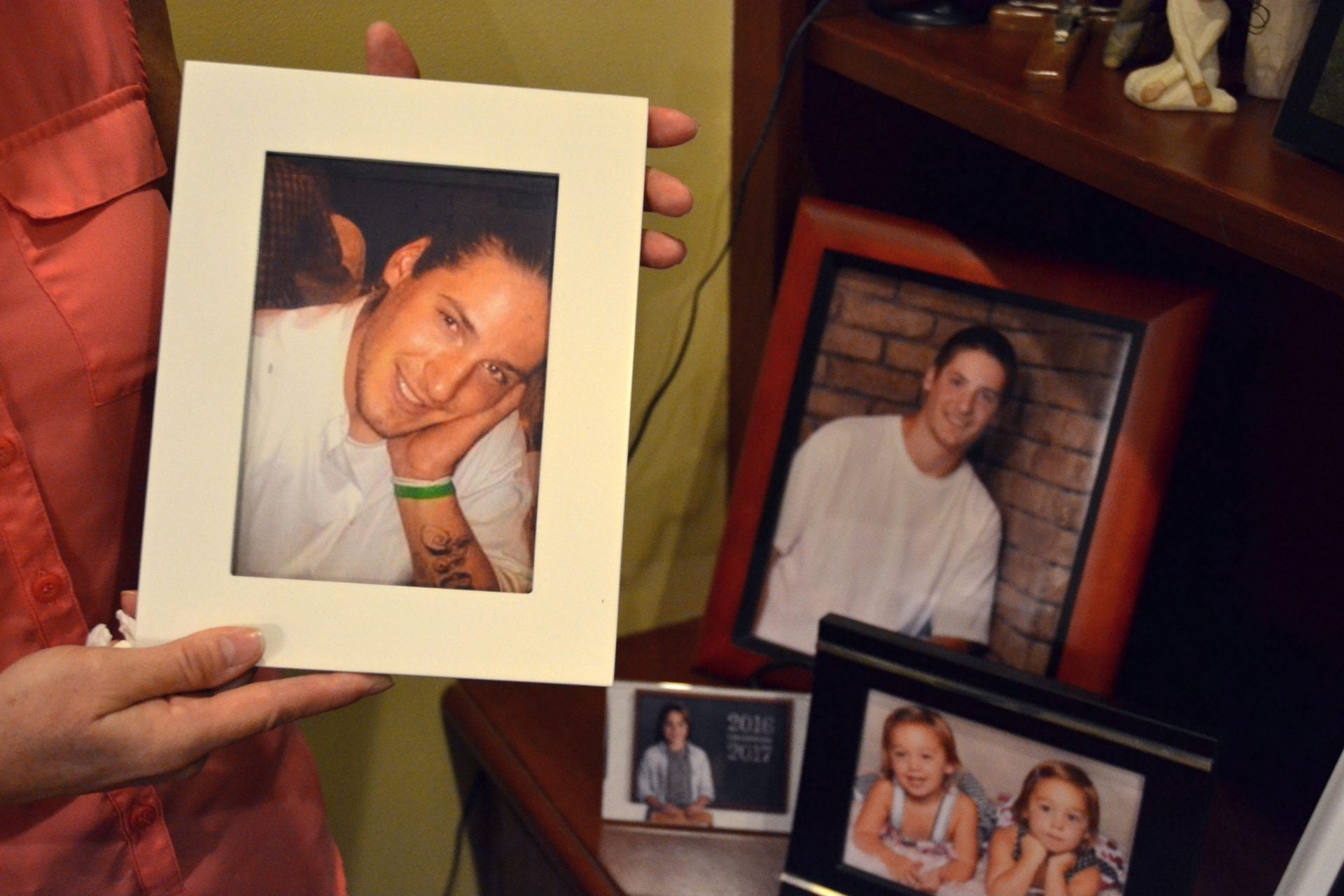

Jeff Sterner adjusts a flower display on his son Joshua’s grave. Josh was 19 in 2012 when he died by suicide. (Brett Sholtis / Transforming Health)

This story originally appeared on PA Post.

—

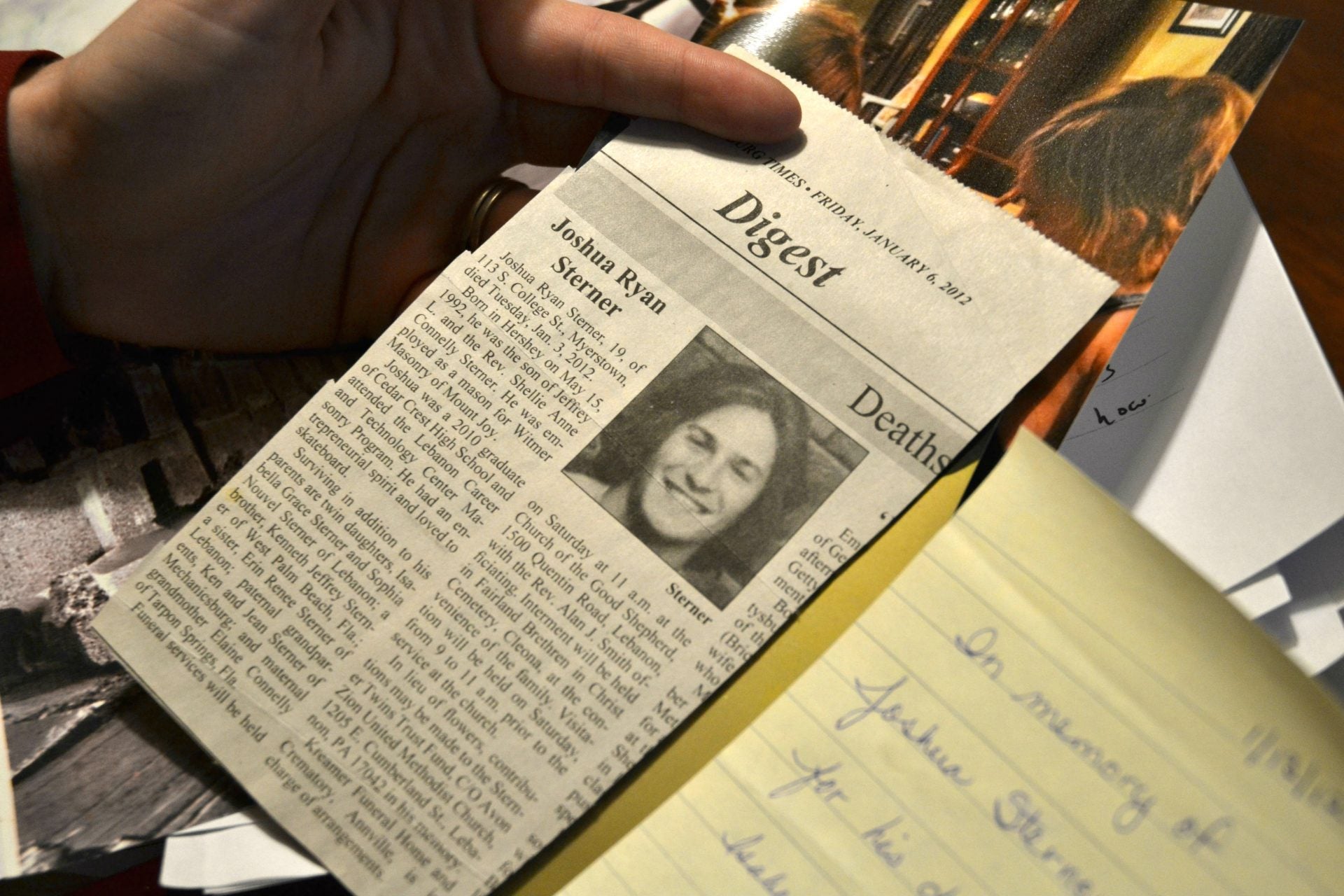

On January 3, 2012, Joshua Sterner drove to his parents’ house in Lebanon to get a hunting rifle.

At 19 years old, Joshua’s life had been derailed by an anxiety-depressive disorder first diagnosed when he was 12. His teen years were marked with angry outbursts, after which he’d withdraw from others.

That disorder recently led to two weeks in WellSpan Philhaven hospital, followed by a return to the stresses of fatherhood and adulthood. According to his sister Erin, he wasn’t sleeping well, had been working long hours as a mason, and his relationship with his girlfriend had fallen apart.

On that day Erin, then 22 years old, was at her parents’ house, on winter break from Penn State Harrisburg. She was worried about Josh. She had last seen him at a Christmas Eve church service where Josh declined their parents’ invitation to visit, saying he just wanted to be alone.

She was at their parents’ home when Josh walked in the door. He brushed aside her questions as he went upstairs. He came down with the rifle. When Erin asked him what he was doing, he told her he planned to kill himself.

Erin followed him outside. She clutched his arm, but her tall, athletic brother easily broke her grasp. She begged him not to hurt himself. Josh told her he loved her, but he made no promise to her.

Hours later, Joshua ended his life. From then on, the Sterners were survivors, grieving a loved one who died by suicide.

Each year, about 45,000 people claim their own lives in the United States, according to Centers for Disease Control. Suicide rates have increased 30 percent since 1999, with some of the greatest increase among people 15 to 24 years old. Of the people who died by suicide in 2012, Josh was one of the roughly 50 percent who used a firearm.

For the Sterner family, however, their loss doesn’t represent some trend or talking point. What began with Joshua’s mental illness led the family down a path of grief and healing. For every suicide statistic, there’s a family left to pick up the pieces, including some who may never heal or who suffer irreparable damage. For this family, telling their story is part of the healing process.

Searching for answers

After Josh’s death, Shellie Sterner revisited her memories, looking for evidence of what went wrong.

She remembered how Josh would throw tantrums as a baby. She remembered how stressed school made him. She pointed to how attached Josh was to her as a child, how he’d cry when she left the room.

“I particularly struggled the most with the sense of the ‘what ifs,’” Shellie said. “Was there something we missed?”

The 55-year-old former pastor at Avon Zion United Methodist Church in Lebanon said Josh had good psychiatric care. He had a therapist. He had access to medication.

Josh had recently gotten a new prescription, and Shellie believed the psychiatrist hadn’t checked in to see how her son was doing.

Shellie also thinks about how easy it was for Josh to get the firearm. She emphasized if she had known the rifle was in her home, she would have had it removed.

The weapon once belonged to Joshua’s grandfather, who’d given it to his grandson as a gift. Shellie thought the rifle was locked in a safe at Josh’s ex-girlfriend’s parents’ house.

“We know statistically that firearms are the leading cause of death by suicide, particularly among men,” Shellie said. “I think that certainly was a part of this story and is a part of this story.”

It would be easier, perhaps, if there was someone to blame, someone at fault. But to Shellie, there weren’t any easy answers.

Shellie said Joshua had family, friends and access to more health care than many people, and yet it didn’t prevent the worst possible outcome. If anything, she said, his death points to the limits of the health care sector’s ability to help someone battling depression.

The firearm, the depression, the anxiety and the stress of recent life events all came together with devastating timing, Erin said.

Puzzle pieces

Shellie left the ministry after her son’s death. For a while, she was angry, even as she held onto her faith.

“If it wasn’t for our faith, I don’t know how you survive this kind of loss, and I don’t mean in the sense that it provides answers, because there are no answers that are satisfying to us as to why our son is no longer here,” Shellie said.

Her husband Jeff broke down when asked how his son’s death affected his faith. It’s something he hasn’t been able to reconcile.

“I have all these puzzle pieces of a life that don’t go together at all,” he said.

Fifty-eight-year-old Jeff is president and chief operating officer of High Industries, a Lancaster-based construction firm. He said the pain of his son’s death was only made worse by well-meaning people who suggested that there was some reason for why it happened.

“An unbelievably insensitive approach, that for anybody to try to tell someone that suffered a tragedy of losing a child or is walking with someone in the complexities of all this stuff, and just say that it’s because God’s plan—that’s not my God.”

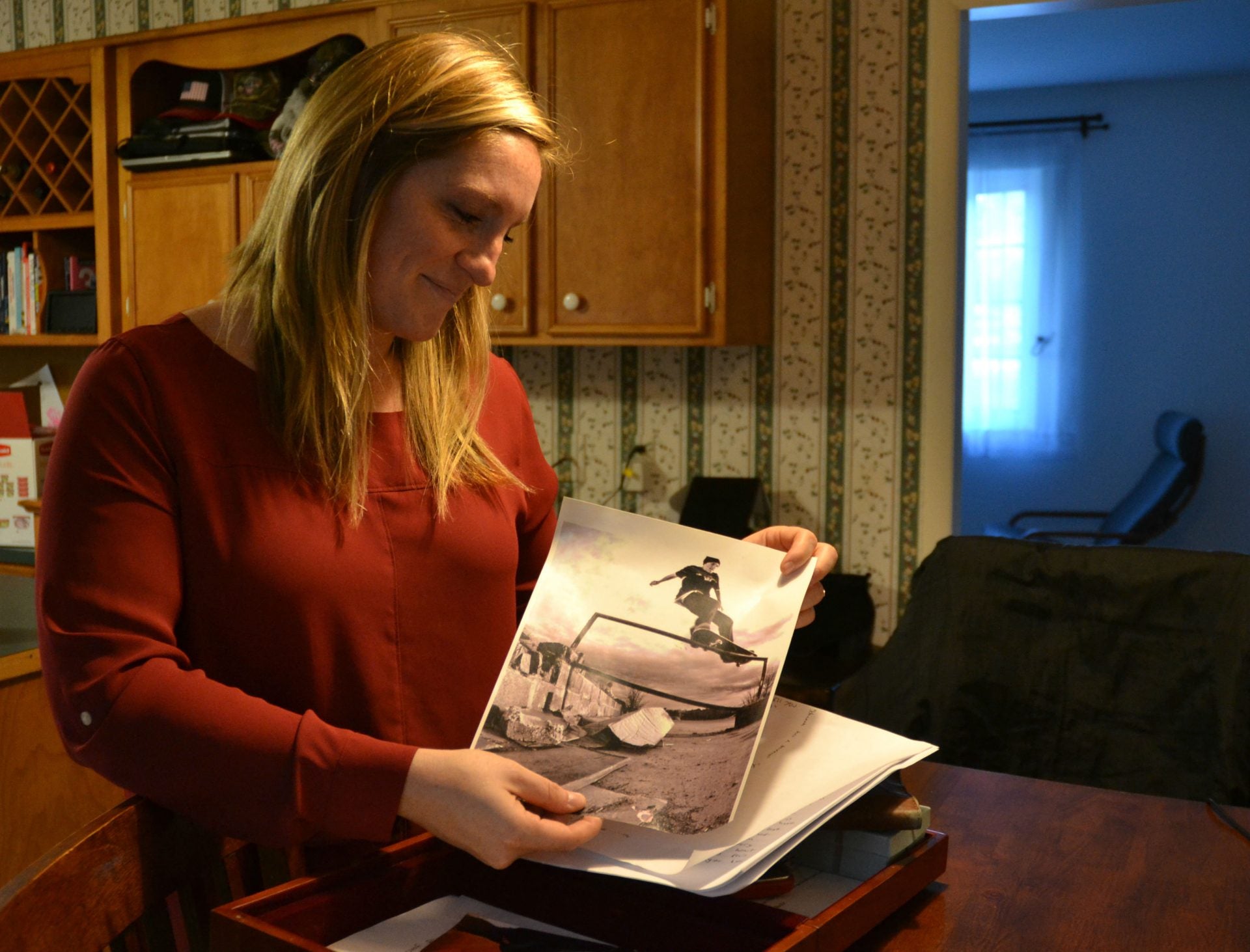

Erin took two weeks off from school. She broke up with her college boyfriend, saying she needed to focus on healing. She was consumed with guilt.

“Everything that was normal was ripped away. The sibling I was the closest to … wasn’t there. But what was left in its place was the guilt that I couldn’t be the sibling that could be there for him.”

Seeking help

Jeff, Shellie and Erin each sought grief counseling.

For Erin, the loss of her brother came up in surprising ways. She spent a year in counseling, plagued with feelings of guilt. Three years later, her grief resurfaced, and she returned to her therapist.

Now, almost seven years since his death, Erin is 28 years old, married with two young children. Josh died before she ever met her husband, and he’s struggled to understand her fears. Erin said he suggested marriage counseling after he pointed out that she was terrified of leaving her children alone for more than a short time.

“I started to realize, wow, a lot of these behaviors I’m exerting now in my own marriage is because of fears that have nothing to do with my husband, but everything to do with [that] I lost my brother. And it was almost as if, when she said his name and said the incident, and I broke down, and then I realized how still connected it is for me, and probably will always be.”

People who lose a loved one to suicide face increased risk of depression, substance abuse and their own suicide, said Shauna Springer, a psychologist who works for Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors.

Springer, who works mostly with families who have lost military veterans to suicide, said there is hope for those who lose a loved one. She uses the phrase “post-traumatic growth,” meaning the loss of a loved one can lead people to change in a positive way — but only if they address their grief and trauma.

“So in having that experience in the population of those who have been impacted by suicide loss, there is a possibility if we’re intentional about helping people … to move them through grief and help them become in some ways stronger than they were even before and sort of living more intentionally in more purpose-filled ways,” Springer said.

Finding purpose

There is no right way for people to overcome this kind of loss and find that purpose, Springer said. For the Sterners, each family member has followed their own path.

Jeff focuses on helping to raise Josh’s twin daughters. He’s also spoken publicly at a seminary conference about facing challenges to his faith.

“Picture a rock climber on the side of a sheer cliff, fingernails dug into the wall, trying to hold on,” he said he told that audience. “That’s where my faith journey is. It’s a little bit better now.”

Shellie has moved her ministry to places she’d never been. She volunteered in grief support with women at Lebanon County Correctional Facility. She now works as a chaplain in a one-year residency at Lebanon County Veterans Affairs.

“Where I’m the most drawn to are the hurting places,” she said.

For Erin, losing her brother has given her greater compassion for others. She doesn’t judge people.

“You just don’t know anyone’s story because from the outside, we literally looked like the picture-perfect family,” she said. “I mean, there’s so much you don’t know. And so much pain you don’t see.”

With Josh and Erin’s children gathered around the dinner table on a weeknight in November, a few days before Thanksgiving, Jeff said they also honor Josh by sharing his story.

They can’t change anything, but they can remember him, he said. And while tragedy risks driving a family apart, it’s brought his family closer together.

“Josh is the glue of this family to this very day,” Jeff said. “He will always have an impact on this family.”

—

If you are in crisis, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273 TALK (8255) or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741.

—

This story is part of Transforming Health and PA Post’s mental health series Through the Cracks, which seeks to locate problems in Pa. mental health services and break down stigma by sharing personal accounts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.