The not-quite-white lies of a Syrian-American

"So what are you, anyway?" — It's a question I dread. I'm third generation Syrian-American, and there are reasons why I've never been vocal about it.

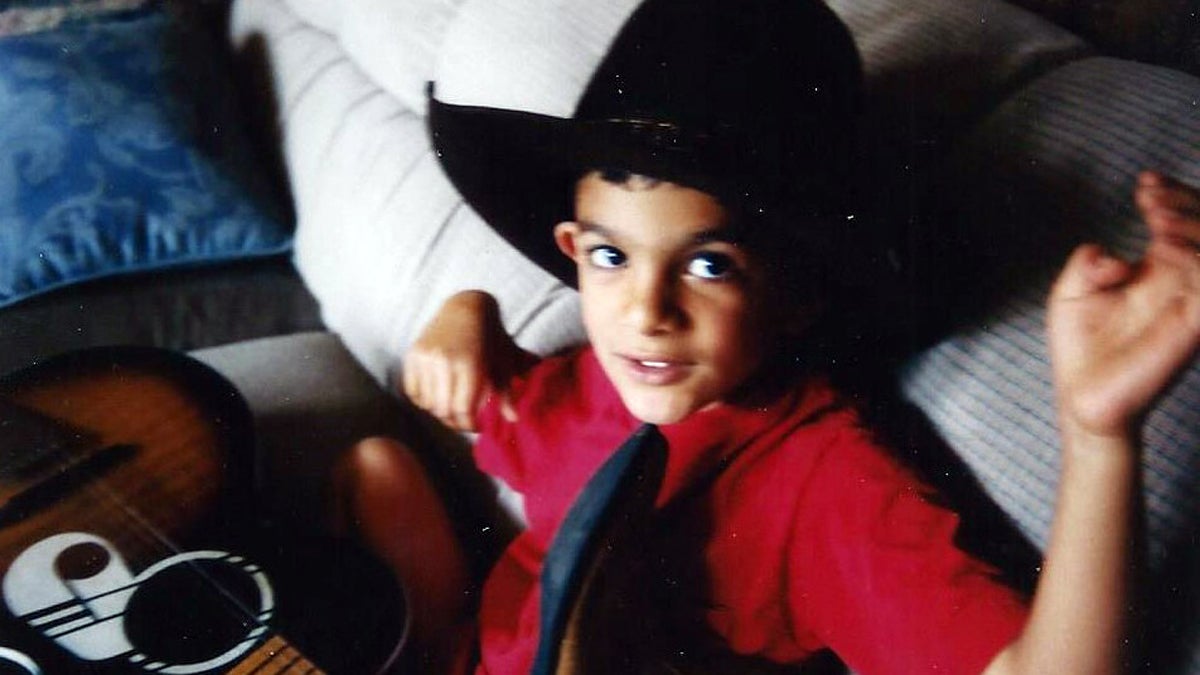

Tony Abraham knew from an early age that he would have to dress the part to be considered 'American.' He is shown here at age 4. 'All that's missing from this photo is a raggedy dog and a T-Bone steak,' he says.

This is part of a series of essays called “Being [Blank] in Philly,” about what it’s like to be you in Philadelphia. In an attempt to discuss the issues that make us different from each other in a respectful and productive way, all readers are invited to submit an essay to speakeasy@newsworks.org to contribute to the series.

—

“So what are you, anyway?”

It’s a question I dread, and one I anticipate fielding every time I meet somebody new. There’s no way I could just be American, right? Someone who looks like me couldn’t possibly be just American.

I’m third generation Syrian-American, and there are reasons why I’ve never been vocal about it.

When I was younger, and up until I graduated from college, I would lie by telling people I was Brazilian or Italian just to keep the conversation rolling. Any nationality — as long as it wasn’t too white — would give me an opportunity to dodge the inevitable leap people would make from “people of Middle Eastern descent” to “terrorism.” I found a temporary, necessary solace in those lies.

But they were still lies. And each one weighed on my conscience. Why should I have to hide my heritage? Every lie nudged me closer to the brink of a full-blown identity crisis, to the point where I, myself, asked, “What am I, anyway?”

Racism, paranoia and ignorance

Last summer, I saw an elderly white woman struggling with a large suitcase down the subway steps at 8th and Market. So I offered to lend her a hand. She was hesitant, but she quickly realized she could not handle it herself.

“You know, I don’t usually like Muslim boys,” she casually mentioned on our way down, “but you seem nice.”

Aw, shucks. Glad to help, lady. I’m not even Muslim.

But that doesn’t stop people from assuming I am. I’m not bothered by the religious association. Islam is just one path toward a moral and ethical life. What irks me is the collective paranoia of culturally ignorant Americans who see someone like me and automatically think 9/11 or ISIS — or, now, Charlie Hebdo. It’s like a demented Rorschach test.

The American psyche is dominated by terrorism. The War on Terror has vilified Muslims the same way WWII vilified the Japanese and the Cold War vilified the Russians. Arab does not equal Muslim. Islam is a faith, not a nation. To assume I’m Muslim is utter racism, and the negative stigma attached to that religion drives my paranoia about the way I look.

Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain

Look — I may have caramel-colored skin, but I’m a quarter Irish. I can dance through a Syrian cookbook, but I couldn’t even stumble through a Syrian movie. Hell, I don’t even know a lick of Arabic — other than the cuss words, of course.

There’s a circle dance performed by Arabs at celebrations called a dabke, which I can only describe as a fusion of Footloose line dance and Crip walk — with a sensual Arab twist. I was at a cousin’s wedding recently, and neither I nor any of my umpteen cousins knew what the hell we were doing. But when the electric slide came on? I imagine it was a lot less painful for people to watch.

I am, as have my father and grandfathers always been, an American first and of Syrian descent second. My grandfathers were both raised during a point in American history when foreigners took pride in being American. Being “foreign” was the last thing an immigrant wanted. And while my grandfathers were still pretty heavily involved in the local Syrian community through its social hub, the Eastern Orthodox church, that mindset — “American first, Syrian second” — was passed down.

By the time I was a teenager, I had totally detached myself from the church and, subsequently, the local Syrian population. Now I feel like a foreigner whenever I’m around other Syrian Americans, no matter their religion. Some Syrian traditions still persist in my family. I’m proud of those traditions, just as I’m proud of my heritage. But heritage is all it will ever be. In no way does it define my whole person.

It’s not my ethnicity I’m ashamed of; it’s the population of Americans who associate my ethnicity with terrorism and Muslim extremism.

A few years ago, I lived by myself in a studio apartment in a predominantly black neighborhood in North Philadelphia. (I was the only non-black person living on that block.) I lived there for four months before any of my neighbors would even look me in the eye.

“That Muslim, man,” I would hear them say. “He’s in the wrong neighborhood.”

I heard it again and again. Did I move? Hell no. I stood my ground. Moving would have affirmed their fears. Plus it would have been super expensive, and I just didn’t have the money for it. So I made it my mission to talk to as many neighbors as I could, every day. By the end of my lease, neighbors were greeting me every morning, inviting me to block parties … and never once did I tell them I wasn’t Muslim. I just never saw the need.

My faith is none of their business. So, when racists of all shapes, sizes and color assume I am Muslim just because of the way I look, I generally don’t try to change their minds. It’s not an argument worth having. But I won’t let them be afraid of me.

I can sympathize with American fear of Islam. People are instinctively cautious of things we do not understand and ideas we cannot comprehend. The last two decades have seen horrific atrocities committed by Islamic extremists. I shared in the nationwide anger, agony and anxiety that followed 9/11. It was as dreadful and heinous an experience for me as it was for all my fellow Americans.

But that mindset needs to change. It’s primitive and simple-minded, the hallmark of a stunted culture far too willing to accept a sacrificial scapegoat. I can’t help but wonder: If I’m paranoid about people perceiving me as a Muslim, how do observant, pacifist Muslims feel when they leave their homes every morning?

Maybe it’s unreasonable or naive to expect bigots to cast their prejudices to the wind. I will, however, not shy away from expecting this: If, by some unreasonably relentless force of curiosity, you ask someone — “So, what are you, anyway?” — be ready to accept “I’m American” as their answer. Because I’m an American, dammit, and it’s all I’ve ever known.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.