The architect behind Schuylkill Yards’ big, red tower wants you to believe in Philly

PAU founder Vishaan Chakrabarti on how Philadelphia can rebound from the pandemic and emerge with a more equitable and ecological way of life.

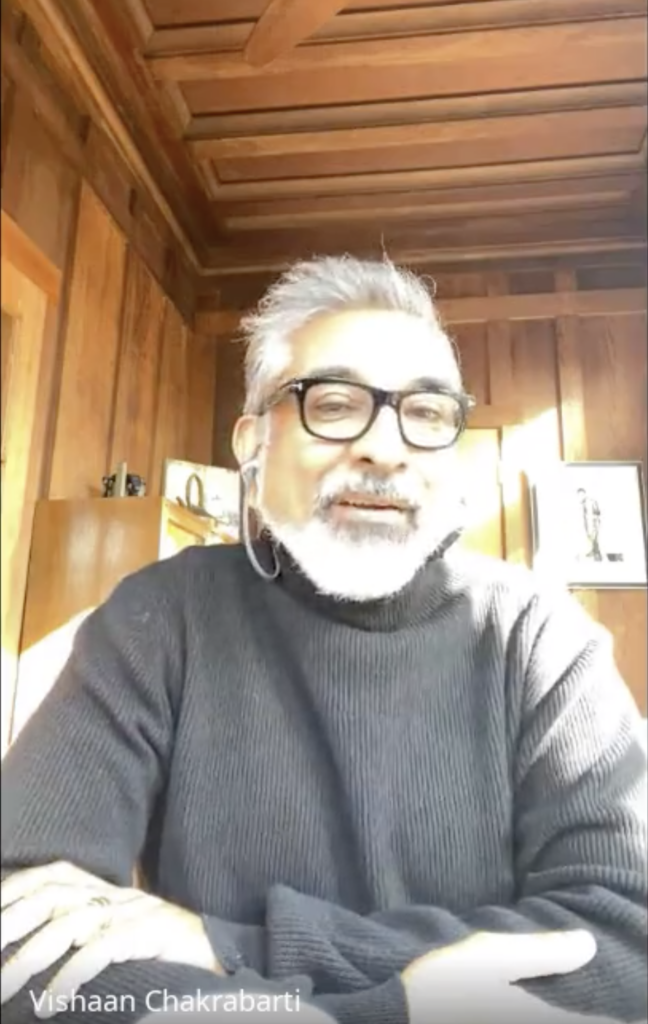

Vishaan Chakrabarti (Courtesy of Bret HartmanTED)

Architect Vishaan Chakrabarti is explaining why he doesn’t think the pandemic will drive people away from cities from a remote office that appears in his Google Meet video to resemble a Finnish sauna.

“Cities and density did not form out of economic necessity. That is an idea that economists and technologists have been trying to foist on us for centuries,” the founder and creative director of the Practice for Architecture and Urbanism and dean of the UC Berkeley College of Environmental Design says.

He gazes at the screen, wearing a black mock turtleneck sweater, and ticks off ancient cities that formed for spiritual or cultural reasons.

“Human beings are social creatures and we need to see each other — and this pandemic proves how much we all miss each other. I still have a tremendous amount of faith in density,” he says. “But that doesn’t mean we should be rebuilding the same inequitable and unecological cities that we had prior to the pandemic. ”

For the architect, who will speak Thursday at a virtual panel hosted by the Philadelphia Arts+Business Council, the future of Philadelphia depends on people choosing it. For the tax base to return, people have to opt into the city over the cozy, athleisure-clad promise of remote work. Sun-lit, wood-walled personal office be damned.

“In a service economy, companies locate and do things based on where human capital wants to be, right? Like, I own an architecture firm, which means I own nothing… What I have is the extraordinary talents of my staff,” Chakrabarti says. “If I say I don’t want to pay rent anymore and everyone can just work from home, I think, over time, the quality of my staff is really going to erode because I have to believe that young people don’t want to just be working out of their mother’s basements and instead, want the life and vitality of the city.”

The onetime director of the Manhattan office of New York’s Department of City Planning first made headlines in Philadelphia in September of 2019. He came to Philly to present two skyscrapers PAU designed for Schuylkill Yards to the city’s Civic Design Review Board.

Brandywine Realty Trust and its CEO Jerry Sweeney wanted architecture that could set the 14-acre West Philadelphia megadevelopment apart, and PAU delivered that in the form of a fire-engine red tower with a postmodern arched arcade on the ground level.

Eighteen months and one pandemic later, the project’s thousands of square feet of commercial office and retail space is moving forward in a vastly different market.

Chakrabarti isn’t worried about Schuylkill Yards though. First, there is the Silicon Valley-endorsed theory behind the district that still holds allure to potential bioscience and tech industry tenants.

“The data that says that when you put a bunch of innovative people together in an urban neighborhood and they run into each other in stores and parks and so forth and train stations, that it generates more patents, it generates more ideas,” he explains.

Then, of course, there are the buildings themselves, newly designed for more airflow and less crowding.

“To the extent that people want to be in cities, newer office buildings will always have the comparative advantage that they’re going to be designed with state-of-the-art systems,” he says.

Offices into housing, storefronts into ‘social infrastructure’

Still, the pandemic has undoubtedly changed the equation for those commercial districts already standing. Like Center City.

After a rough 2020 that saw offices close en masse and hundreds of storefronts boarded up, 2021 has begun on a better note for the city, but the troubles are far from over. The number of workers walking on downtown sidewalks in January was 76% below foot traffic levels from the prior year, according to a report released in February by the Center City District. The number of shoppers in from outside the city and tourists on downtown streets was down by more than half.

“This happened after 9/11 when I was Manhattan director,” Chakrabarti says. “People had many of the same questions about downtown. It was emptied out in Lower Manhattan and the [rebound] was really about the fact that people believed in New York. They wanted the culture back.”

The former city official sees lessons for the City of Brotherly Love there.

“If Philadelphians believe in their city, the office market and everything will return,” he says.

But there is another lesson there too, about economic adaptation. Lower Manhattan came back from 9/11 with far fewer offices and many more luxury condos. The devastation of 9/11 accelerated a trend toward residential conversion seeded by a generous tax break for residential retrofits.

In Center City, the same trendline has brought thousands of people downtown to live in new apartments and condos built over the last two decades. In 2019 alone, more than 2,000 new units of housing were built, according to Center City District.

The shift toward a more residential Center City could greatly and quickly accelerate as companies decide to keep some or all of their employees working remotely. That could be a good thing if decision-makers steer the redevelopment to meet affordability demands, according to Chakrabarti.

“There’s a huge opportunity for the [old office buildings] to become forms of affordable housing,” he says, adding that retrofitting offices could be less expensive than creating units from scratch. Plus, the fact that they are already standing means no one can argue against them on the basis that they would disrupt the “fabric” of the neighborhood, he notes.

Chakrabarti may not be the only one seeing that opportunity. Four new residential developments are underway in Center City, according to the February Center City District report, and interest in living downtown hasn’t waned.

“Contrary to fears of urban flight, both the volume of transactions and sale prices rose in 2020 for homes in Center City and the city as a whole,” the report notes.

A ‘false choice’ for cities

In Chakrabarti’s 2013 book, “A Country of Cities: A Manifesto for an Urban America,” he describes the distinction between “easy urbanism” and the urbanism he advocates for, defined by a population with enough density to support mass transit.

“This definition is not intended to belittle places of lesser density; it simply asserts that while villages, towns, and suburbs may exhibit some of the same valuable characteristics as much denser environments, they cannot be scaled to accommodate the millions that big cities with metros can so effectively house,” he wrote.

When PlanPhilly asked him how a city like Philadelphia can reconcile its need for more housing near transit with the affordability problems and displacement pressures that come with development in low-income neighborhoods, he looks down for a few seconds before looking back through the screen and launching into a response that could itself be a book pitch. He gets this question often.

“The problem we have across the United States is we’ve been given a false choice for the future of our cities. We’ve been told that our cities are one of two things: the failing bankrupt, crime-ridden cities of the 1970s, or the bourgeois, gentrified cities of more recent history. And that’s our choice. If we want a tax base, then we need chain stores and gentrification. Otherwise, we have no tax base and cities become a horror story.”

The reason for that false choice, he says, “is the full-scale withdrawal of the federal government from urban policy and public housing.”

Without more support from Washington, “cities don’t have the wherewithal to resist the pressures of gentrification.”

In other words, believe in Philly and push federal officials for aid. Chakrabarti, for one, is optimistic about the Biden administration.

“What’s interesting is the people who are painted as adversaries, say developers versus community activists. To me, that’s focusing on the wrong battle, because both of those groups have been disarmed and none of them have the tools that they need to build more affordable housing close to where people work and go to school … So I’m sure Philadelphia could lean in and do the right things here in terms of building more affordable housing and stemming the tide of gentrification. But they can’t do that without a strong federal partner.”

To hear more from Vishaan Chakrabarti, register for Thursday’s virtual panel, Industry Intersections: Art, Design + Development, hosted by the Arts + Business Council.

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.