Temple voice therapy program speaks to transgender women

Hormones that help with transition don’t change the pitch of the voice, but vocal therapy programs like the one at Temple University's College of Public Health can.

Listen 3:09

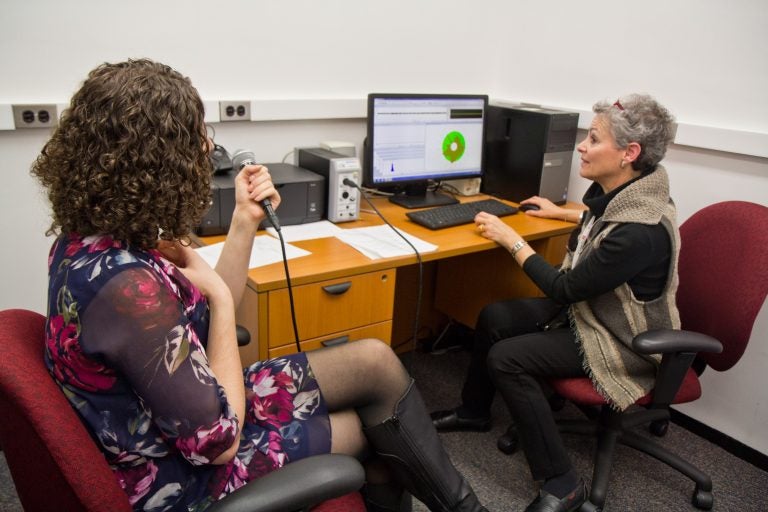

Ann Addis, Temple University clinical instructor and speech pathologist, (right) demonstrates how pitch is measured in the lab. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

When Erica Cirulli decided she was ready to start presenting as female, she got all her ducks in a row.

She started taking hormones and made a plan for how to come out to the people she cared about. She prepared to tell her colleagues at the accounting firm where she works.

And then, there was her voice. She knew she wanted it to change to match her appearance, but she was worried about losing its character, too. She felt connected to her voice.

“I was pretty terrified,” Cirulli remembered. “My voice was very deep before. I think it was a very notable characteristic of who I was before, so I wanted to make sure that this new voice was as notable, as strong, as commanding as I felt like I was before.”

At the time, Cirulli didn’t have insurance to cover any sort of treatment related to sex or gender reassignment. A therapist recommended the free voice clinic at Temple University’s College of Public Health.

The clinic has been around for years, offering services to people with a wide range of speech disorders, from language delays to complications resulting from a stroke. But in the past few years, the weekly hour-long sessions taught by graduate students have become popular among women who are transitioning. In fact, the majority of the clients are trans women now, and so is most on the considerable wait list.

For those transitioning from female to male, the hormone testosterone helps lower the pitch of the voice. But that’s not the case for the hormones taken by transgender women, so barring expensive surgery, voice therapy can be the only option.

Therapy is not cheap either since it’s usually not covered by insurance. Many trans women look to YouTube videos to self-teach, and while that can be affordable and accessible, it can also be dangerous.

“We’ve heard from some clients that they found sources online that suggested that they target their falsetto range for speaking,” said Ann Addis, who supervises the Temple clinic. “But that can be very damaging to the vocal folds, if you have a structure that is designed to produce a certain sound because of the size of the vocal cords, and you’re asking to produce a sound that’s much higher, you could put a lot of strain on the mechanism, and those are very delicate muscles.”

Plus, said Addis, you can’t get feedback from the internet, telling you how natural you sound.

After a few months, Cirulli had trained the muscles in her larynx to raise the pitch of her voice. But she wasn’t presenting as female full time yet, which meant she didn’t have a lot of opportunities to practice. Cirulli had wanted to get ahead of the curve by starting voice therapy before she began dressing and identifying as a woman consistently in public. That meant she was using her female range only in voice class, or with her therapist, or on the phone with a couple people to whom she had already come out.

“It’s a catch-22,” Cirulli said. “You want the voice down to be able to go full time, but I didn’t feel like I could nail the voice until I was already full time.”

Even though she didn’t quite feel like her voice was ready, Cirulli started presenting as female full time. It wasn’t without its complications, she said: She was misgendered and had to correct people — all the time.

“It’s an awkward phase,” she said and laughed. “Whether you’re growing your hair out or going through puberty, or going through my second puberty right now, you’ve got to accept and embrace the awkwardness because it’s not going to be perfect and you’ve got to make it better over time.”

More than just pitch

Walk, jump, step, fall. It’s a standard American speech pattern, common for women.

Think about how you might hear the sentence, “I just went to the store.” It starts out slowly. Then, the word “just” gets the most emphasis — that’s the jump. The stress on words decreases gradually from there and falls at the end of the sentence.

That last bit, where the pitch lowers and the bottom falls out of the word, was the scariest for Cirulli.

“I was always terrified of my voice getting low for that fall, so it always ended up neutral or monotone,” she explained.

But that felt like she was overcompensating — it didn’t feel natural for her.

“It sounded kind of robotic,” she said.

Cirulli started working with Hilary Waller, a graduate student in Temple’s speech and language pathology program. Pretty soon, they realized that part of why it was feeling awkward for Cirulli was that they had targeted too high a vocal range.

“We decided to move into gender-ambiguous zone because it was comfortable for her, a more natural way of speaking,” Waller said. “Then along with that, it was easier for her to work on forward resonance, breathiness, and intonation.”

Those additional elements are part of what makes in-person therapy so helpful. While pitch refers to your voice frequency, resonance describes its origin. Men tend to have a deeper resonance, coming from the chest, while women tend to resonate from their throats and mouths.

Addis, the faculty supervisor, said it’s just a matter of muscle memorization and drills to get this stuff right.

“It’s drudgery, right? We practice a set of techniques, get consistent response, then we come back, we tweak it, we up the level, go home and practice, and it goes on for generally two semesters,” she said.

After another semester working with Waller, not only had the two become friends but Cirulli felt as if when she spoke, she sounded like herself.

“It’s even weird, noticing this internal monologue,” she said. “You know when you think, and the speech you have in your head? That’s switched to this too.”

“I spoke like that for 27 years, and I only spoke like this for one.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.