Swarthmore College students, faculty launch Delco’s first homicide database

Advocates hope the Delaware County Homicide Database will help reduce gun violence. It documents 503 homicides from 2005 to 2019.

Listen 4:12

Heeding God’s Call to End Gun Violence installed their memorial to the lost at Trinity Episcopal Church in Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, U.S.A. in September 2018. The memorial travels around Delaware County. (Lee Smithey)

Some Swarthmore College students and faculty, in collaboration with local groups and activists, have launched Delaware County’s first interactive homicide database with this goal in mind — reducing gun violence.

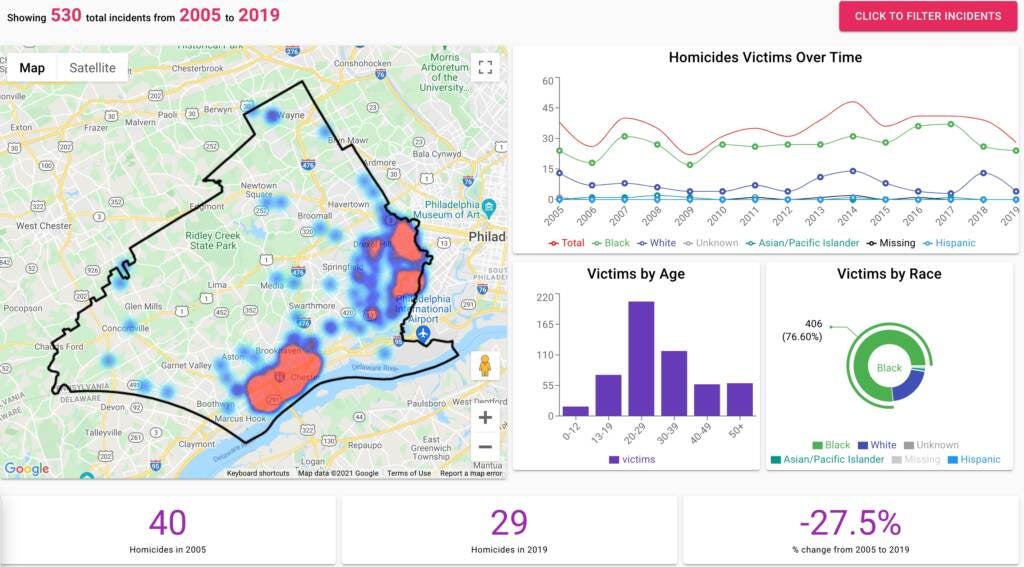

The Delaware County Homicide Database went live on Oct. 27, documenting the 503 homicides that occurred from 2005 to 2019. Cases are further broken down by year, age, race, weapon type, and other categories. A map shows where each incident occurred.

The database is the culmination of years of effort.

Lee Smithey, a professor of peace and conflict studies and sociology at Swarthmore, teaches a course called “Gun Violence Prevention.” Since 2013, students in his class have worked with activists and local groups — among them, Delaware County United for Sensible Gun Policy, now a chapter of CeaseFire PA — to research those deaths.

“And after a number of conversations, we came up with this idea of a database of homicide … homicides, which, sadly, are mostly gun homicides in Delaware County. And we’ve been working on that ever since,” Smithey said.

Using data from the Pennsylvania Uniform Crime Report and details from area news outlets, the 43 students that have taken Smithey’s course since spring 2013 organized the information and crunched the numbers.

Smithey wants to make one thing clear: This should not be confused with a gun violence tracker. Non-fatal shootings are obviously not included in a database tracking homicides — that would have been a tall order, he said, because data on non-fatal shootings is spread out among medical and law enforcement sources, with some incidents not reported at all.

“I think it would be great if we had more open data at the county level in order to be able to track gun violence, shootings, not just homicides. But we focused on homicides, because that was a reachable target for us in a semester context,” Smithey said.

Delaware County United for Sensible Gun Policy served as a catalyst for getting the project off the ground, but another source served as an inspiration of sorts. Smithey said that Jim McMillan, director of the Philadelphia Center for Gun Violence Reporting, once taught a peace journalism course at Swarthmore, and that conversations with him helped guide the vision for the gun violence course.

The project was not without its hurdles. Data can be stubborn, and access can be difficult.

“The Uniform Crime Report, for example, right now is being transferred over to another system, the National Incident Based Reporting System, and that caused a bit of a kink for us the last time I taught the class, because we had difficulty downloading and getting that basic data from law enforcement about homicides in the county,” Smithey said.

Sometimes, the extra digging can be instructive; other times, it can be tedious. Journalism partners helped fill in some of the gaps in the numbers. Yet local journalism organizations are often under pressure financially these days, and a reporter’s bandwidth can only stretch so far, leaving gaps as well.

The students didn’t get discouraged. They went above and beyond.

“We were looking at everything from news articles to community obituary pages, blog posts, Facebook posts, a lot of stuff on social media, just trying to really find any information that we could about each of these individual cases of gun violence throughout Delaware County,” said Oliver Hicks, a senior at Swarthmore who took the class in January 2020.

The class was determined not to reduce the tragedy to mere numbers, and instead sought to paint a complete picture of any given incident.

Hicks said he doesn’t want any story to simply “slip through the cracks.”

“We had a lot of conversations about how do we find a balance between presenting a full picture of gun violence in our communities using statistics and data points, but also not losing the kind of grounding, humanizing elements of all of these incidents of gun homicides as well,” Hicks said.

After doing the work, Hicks said, he thinks there is a massive data deficit that will also require a massive effort to address.

Former students who worked on the project have been blowing up Smithey’s email lately, expressing gratitude that the database is finally up and running. He thinks his students deserve praise for being intentional about the work needed to pull off a thorough, yet humanizing data project.

“One of the things that the database does is confirm what we already know about gun homicides, or about homicides in general first … that most homicides involve a gun, and also that young Black men in their 20s are at disproportionate risk of being a victim of gun violence,” Smithey said.

The homicide database also shows an unequal distribution of cases in certain areas of Delaware County.

The class will continue updating the dashboard, but Smithey also hopes the project can expand to address gun violence writ large and become Delco’s version of Philadelphia’s extensive dashboard. That will only happen if partnerships with local hospitals can be developed, he said.

Their work has not gone unnoticed.

Margie Reiley of Havertown, whose son was fatally shot in 2013, said the homicide database is an impressive tool to educate the community and secure funding for community-based anti-gun violence programs, such as the one in Chester.

Her son, Jason McClay, a Navy veteran, was working as a manager at a Rite Aid store in Chester when he was fatally shot during a burglary. He was a great guy who often paid for people’s prescriptions whenever they couldn’t afford them, she said, and she misses him greatly.

She thought she had raised her kids in a safe area.

“How could this ever happen to me? That was my attitude.” Reiley said.

Now, everyone has lost, she said.

“I lost my son. And he lost his family. And everyone that was involved in his murder lost their life too, because there’s three people who are incarcerated for the rest of their lives and there’s two people that are in jail for 30 years. And I told them all, ‘You lost your lives too.’ Nobody wins,” Reiley said. “You just shot the gun once; you lose one person, and you take out 25 or 30.”

Since then, she has focused on the issue. “This is what we have to do to combat gun violence,” Reiley said of the database.

Max Milkman of CeaseFire PA has been working with Reiley to get her story out there. He said the database will be an invaluable tool when asking lawmakers to provide resources.

“It’s a brilliant act of activism for them to take their skills and our knowledge and actually apply it to real-world issues, and applying it to educating our communities on where gun violence actually occurs,” Milkman said.

He hopes it raises the public health alarm in the suburbs, so that gun violence can be addressed at every level of government and not just be brushed off as a city issue.

“Lawmakers cannot sit back and say that gun violence does not impact their communities. We now have a map that clearly shows it does. And I’m hoping that it leads to action and education around this issue,” he said.

After speaking with community partners and immersing himself in the data for nearly a decade, Smithey doesn’t want the project to be misunderstood. Every single incident of homicide is a life lost.

“It’s a moment when the fabric of the community gets torn,” Smithey said.

The homicide database brings the county one step closer to patching itself back together.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![Heminghaus-Silent March for Fanta_003 [in center]: Taylor Kowalski, from Ridley Park, marching alongside others.

The Justice for Fanta Bility silent march in Sharon Hill, PA on 10/17/21. Fanta Bility was an eight year old girl who was shot and killed outside of a football game at Academy Park High School on August 27, 2021. The march had been organized and led by the UDTJ and Delco Resists as a way to honor Fanta’s life as well as call for police accountability.

[DANIELLA HEMINGHAUS]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Heminghaus-Silent-March-for-Fanta_003-360x280.jpg)