Student protesters shut down Philly school board meeting over metal detector vote

The Philadelphia school board voted to require metal detectors at all district high schools; protesters then took over the meeting

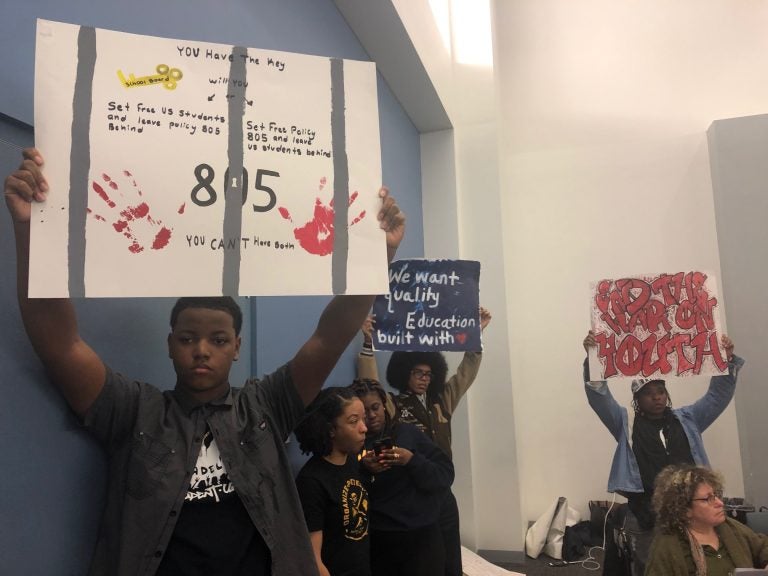

Students hold up signs denouncing Policy 805 prior to the Board’s yes vote that led students and faculty to temporarily shut down the school board meeting. (Darryl Murphy/WHYY)

Protesters shut down Thursday’s Philadelphia School District board meeting after a 7-2 vote to require metal detectors and X-ray machines in every district high school.

Philadelphia Student Union executive director Julien Terrell and around 60 students and faculty who called for a “no” vote on the policy stormed the front of the school board auditorium, denouncing the less than year-old board.

“We do not recognize the legitimacy of this board anymore,” shouted Terrell, who then continued to list alleged cases of malfeasance in the district under Superintendent William Hite, including the alleged assault of two students by school police officers.

“We are not talking about conversations,” shouted Terrell. “We’re not talking about officers being nice. We are talking about the everyday traumatization of students.”

Student advocates campaigned for months against Policy 805 and received support from two school board members. All but board members Mallory Fix-Lopez and Angela McIver voted in favor of the policy. PSU’s Julien Terrell passionately denounces the less than year old board. @WHYYNews pic.twitter.com/hTlx0ba7xx

— Darryl C. Murphy (@darrylcmurphy) March 29, 2019

Terrell continued to speak to an audience of supporters and some district staff. When board President Joyce Wilkerson threatened to have Terrell removed, he reacted in defiance.

“There’s not enough of you all to remove us,” he shouted. And I f–king dare! I dare you to come and remove us!”

The board then called a recess.

Once the board members left, members of the Caucus of Working Educators, a group of progressive teachers, took over the semi-circle desk. Holding up banners and signs, they conducted a meeting of the “People’s Philadelphia School Board,” where teachers and students delivered testimony.

Students and faculty campaigned against the metal detector policy in the weeks leading up to the vote, saying it criminalized students, though the policy essentially targeted three schools that don’t use metal detectors: two Science Leadership Academy campuses and the Workshop School.

They received support from City Councilwoman Helen Gym, who testified against the policy, and urged the board to listen to students.

The policy aims to create uniformity in the district as Science Leadership Academy Center City is set to share a building with Benjamin Franklin High School, which already uses metal detectors.

Board members Mallory Fix-Lopez and Angela McIver openly and consistently opposed the policy for weeks, while those voting in favor argued the policy would help keep students safe.

Board member Julia Danzy called the detectors a “deterrent” to violence that affects the city and traumatizes students. She said it isn’t right for individual schools to be exempt from using metal detectors.

“We need to try to make all areas safe,” said Danzy before the controversial vote. “And, until we do, we need, unfortunately, to have the mechanisms that are available to us to try as much as possible to keep them safe.”

Terrell said the next action will be at City Hall during the City Council budget hearing on May 14 to call out how much the district will spend to carry out the policy.

“We’re going to take this energy to the budget,” said Terrell. “Because if they’re doing this right now, they didn’t talk about the money that’s going to be spent in order to implement that. That’s a budget issue. So if we haven’t won here, we haven’t won in this space, we don’t recognize the legitimacy of this space anymore. We’ll go to City Hall and get the solutions we need.”

According to a statement, the board reconvened in the board committee room “to continue its business.”

“While we always appreciate student voice and community engagement,” it said, “it is important that we have respectful dialogue while dealing with difficult issues.”

Speakers prevented from talking at the meeting will speak first at the next action meeting on April 25. No arrests were made at the demonstration.

Fiscal matters

Prior to the chaos, the district revealed its five-year fiscal projections on Thursday.

Though expenses are still growing faster than revenues, the district’s structural imbalance isn’t as severe as it was a few years ago. Officials expect to end the 2020 and 2021 fiscal years in the black, with deficits re-emerging by 2022.

That may sound dire, but it’s a significantly sunnier picture than before. As recently as two years ago the district projected expenses to rise at nearly twice the rate of revenue, with a five-year projection that left city schools $714 million in the red.

The district still expects costs to grow faster than revenues over the next five years, but the gap is smaller than previously thought. Without new money from the city or state, the district’s costs will rise 3.4 percent between now and fiscal year 2024. Revenues, meanwhile, will rise 3.1 percent.

That trend — if it continues unabated — will leave the district with a $296.7 million deficit in five years.

“It’s always a concern when you see red,” said district CFO Uri Monson. “[But] almost any other school district would look like this,”

Most other districts don’t publish five-year projections, said Monson, because that would raise the specter of tax increases. Philadelphia is the lone Pennsylvania school district that can’t raise its own taxes, which is why officials create these long-term roadmaps. They want to make sure politicians aren’t blindsided by the district’s needs.

“They don’t want to be caught by surprise,” said Monson. “They want to know what’s out there.”

Many Pennsylvania school districts face structural money woes, many of them caused by rising pension, health care, and charter school costs. Philadelphia is no exception. Thanks to new funding from the city and state, the forecast in Pennsylvania’s largest school district now looks about the same as it does in many of the Commonwealth’s smaller school districts.

The relative stability has helped the district add back counselers, nurses, and other positions cuts during past financial crises.

“We still have a long ways to go,” said Hite. “But by the same token, this is a testament to the sacrifices that individuals have made over the past several years.”

“Instead of eliminating, cutting, reducting, we’re now talking about investments,” he added.

The district’s proposed budget for fiscal year 2020 will include nearly $3.4 billion in expenses.

Officials say the plan is to enhance and expand the approach they’ve taken in the first few years of the district’s financial recovery. The district has focused a lot of its new money on teaching reading in grades K through 3. Officials now want to expand those efforts by putting literacy coaches in every fourth- and fifth-grade classroom.

They also plan to add 30 English language-learner teachers, 10 “college- and career-readiness coordinators,” and more nurses.

They’re also planning to pivot from the reading-first focus and update the district math curriculum. Hite said an overhaul is overdue, and that this year will be spent researching best practices. Additional supports for math teachers will arrive in the 2020-21 school year.

“We have to turn our attention to math,” said Hite. “We look at our outcomes with respect to math and there’s a lot of work to be done there.”

One thing that isn’t in the district’s budget is a plan to close schools.

Population loss and the growth of charter schools has left the district with some buildings that are well under capacity. Earlier in the decade, the district closed 30 schools, but the pace of closures and consolidations has slowed in recent years.

Hite acknowledged that the district will still look to contract, but that there are no closings planned right now. He said officials want to be more creative in how they address these problems, citing recent research that showed closures can hurt student performance.

The superintendent talked about cases where the district relocated successful programs in underused school buildings, suggesting it was a less disruptive way to help address infrastructure woes.

“There’s still some consolidation we could do, particularly around comprehensive high schools,” said Hite. “But we have been trying to do this in unique ways.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.