State pension crisis: How did we get here?

Listen

Pennsylvania Senate Majority Leader Jake Corman, R-Centre, insists on systemic changes to state employee pensions before agreeing to any of Governor Tom Wolf's budget proposals. (AP Photo/Chris Knight)

The strategy of kicking the can down the road works — sort of — until the can gets too big and the road narrows.

Pick your favorite issue or cause in Pennsylvania: public education, services for the poor, tax breaks for businesses.

Chances are, there’s going to be less money for any of these moving forward because the state’s public employee pension bill is growing exponentially, with a current unfunded liability of $53 billion.

To keep up with rising costs, school districts across the state have been making tough choices — either cutting programs or hiking property taxes.

School budget wonks are reeling from the massive pension payment spikes that have been hitting lately.

In Philadelphia, for instance, the district has been cut to the bone, and because leaders lack taxing authority, there’s only thing to do each year: beg and plead for more from the city and the state.

“When you have these fixed mandated costs, it handcuffs you in your ability to meet the needs of students because so much of your money is going towards a certain fixed cost item,” said Matt Stanski, chief financial officer of the Philadelphia School District.

Just a few years ago, schools paid about 5.5 percent of employee salary to the pension fund. This year, they must pay 21 percent. Next year, they’ll pay 26 percent. The rate will peak at 32 percent in 2019.

“If they continue to grow without the requisite revenue to help support it,” said Stanski, “the district will continue to be in a situation where we’re asking for money, year-in and year-out to provide basic services for students.”

The state splits the employer pension contribution with school districts, picking up a little less than two-thirds of the cost.

By 2019, the state will need to spend $3.3 billion to meet its total pension obligation — double what it paid last year.

Tracing history

So how did Pennsylvania get into this mess?

You have to go back to the late 1990s. The economy was booming. The state was running a surplus, and the public employee pension funds were flush with cash.

The state runs two pension plans that share a parallel narrative: one plan (called PSERS) is for teachers and school employees. The other — SERS — is for other state workers, which, in addition to rank-and-file state employees, includes state troopers, lawmakers, judges, top executive branch officials and state university staff members.

By the summer of 2001, basking in the sunny glow of a bullish stock market, state lawmakers voted to boost pension benefits — bumping up the pay-out rate and cutting in half the amount of time it took to become eligible for a pension.

But, then, the bottom fell out.

The attacks of 9/11 came, the economy took a downturn, and surpluses were quickly drained.

In 2003, Ed Rendell came into the Governor’s mansion with big plans to boost classroom education spending. And through his two terms in office, neither he nor the legislature made funding state pensions a priority.

They made their required payments, but only by passing laws that artificially lowered the rate.

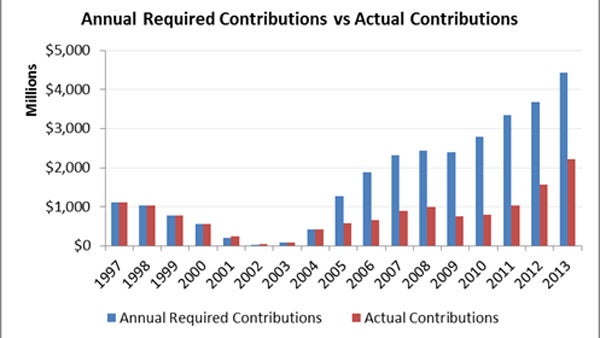

In reality, based on actuarial need, the state continually hasn’t kicked in enough money to cover its growing debt.

And if you’re looking for the single biggest reason for the dire straits the state currently faces, this is it: “You can’t operate a pension plan like the payments are optional,” said Steve Herzenberg, executive director of the Keystone Research Center, a progressive-minded Harrisburg think-tank.

“They’re not. And we acted like they were optional for 12 years, giving corporations tax cuts, funding education more generously,” he said. “So if you don’t pay your credit card, at some point your bill comes due.”

Source: Pew Charitable Trusts, Pennsylvania state pension plan annual required contributions vs. actual contributions.

Compounding the issue, many school districts used the state’s influx in classroom spending to boost employee salaries, which, because pension payouts are based on a percentage of an employee’s final pay, drove up the state’s debt.

Bad gamble

Rendell and state lawmakers believed that the market would rebound, and a surge in the stock market would forgive their underfunding.

Rendell did not respond to an interview request for this story.

Through it all, to this day, state workers made their required contributions, which for teachers is about 7 percent of salary.

By 2007, with Wall Street booming, Rendell’s bet seemed like it just might pay off. But the Great Recession of 2008 swiftly eroded the value of the state pension fund, leaving state lawmakers with a daunting bill they could no longer ignore.

In 2010, Rendell and the legislature took a step to rectify the problem.

They passed Act 120, a bill which undid the generosity of 2001 pension boost for new hires, and pushed up the retirement age.

But many lawmakers, especially conservatives, say Act 120 didn’t go far enough, and Gov. Tom Corbett pushed to end the state pension system altogether. Several pieces of legislation were developed that would move new teachers and state workers into 401k-style plans, ones that don’t guarantee a set retirement benefit.

Even with Republican majorities in both the state house and senate, Corbett and proponents of that tack, though, couldn’t muster the votes to make those bills law.

Through his tenure, like Rendell, Gov. Corbett found priorities other than fully funding the state’s pension debt, such as cutting taxes for businesses.

Pension wars

This leads the state to its present moment, where an ideological battle is brewing in the capitol.

Senate Majority Leader Jake Corman, a Centre County Republican, is insisting on systemic changes before agreeing to any of Governor Wolf’s budget proposals — ones that center around boosting state education spending in classrooms.

Corman wants newly hired teachers and state workers to get 401ks, and wants to reduce unearned benefits for current employees, the latter of which would likely spark a court battle based on contract law.

“This is the elephant in the middle of the room, and until we deal with it, it’s going to drive all conversations,” said Corman.

There are currently about 330,000 retirees receiving a state pension. The average payout to a rank-and-file state employee or teacher is about $25,000 per year.

Last week, the Senate approved a plan along party lines that would require concessions from many of the 370,000 current state government and public school employees. New hires would also no longer receive a pension, instead getting a far less generous retirement package tied to the performance of the stock market.

Gov. Wolf opposes this measure.

He plans to defray some of the coming pension increases in a few relatively small ways: refinancing the debt, cutting Wall Street management fees, and dedicating funding to pensions from modernizing state liquor stores.

But, when it gets down to it, Wolf says, as painful as it may be, the state just has to pay its bill.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.