St. Joe’s reopens the old Barnes Foundation building as a new museum

St Joseph’s University acquired Albert Barnes’ original galleries in Lower Merion, to open its first campus art museum in 172 years.

Listen 1:29

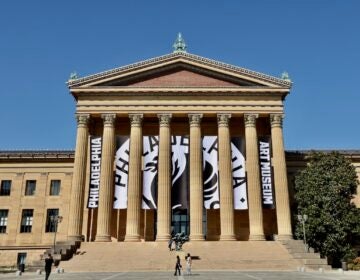

The exterior of the new Frances M. Maguire Art Museum has been preserved and restored with the original design by architect Paul Cret. (Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

The original Barnes Foundation building in Lower Merion, which the foundation left in 2012 to move to the Parkway in Philadelphia, is now exhibiting art again. St. Joseph’s University has completed extensive renovations to the building which will open this weekend as the Frances M. Maguire Art Museum.

St. Joe’s has a collection of about 3,000-pieces of art. For the first time in its 172-year history, it now has a museum in which to put them.

“It’s an iconic building, but to have a 21st century university museum it needs to be modern as well,” said university president Cheryl McConnell. “Filled with technology and new ways to experience art.”

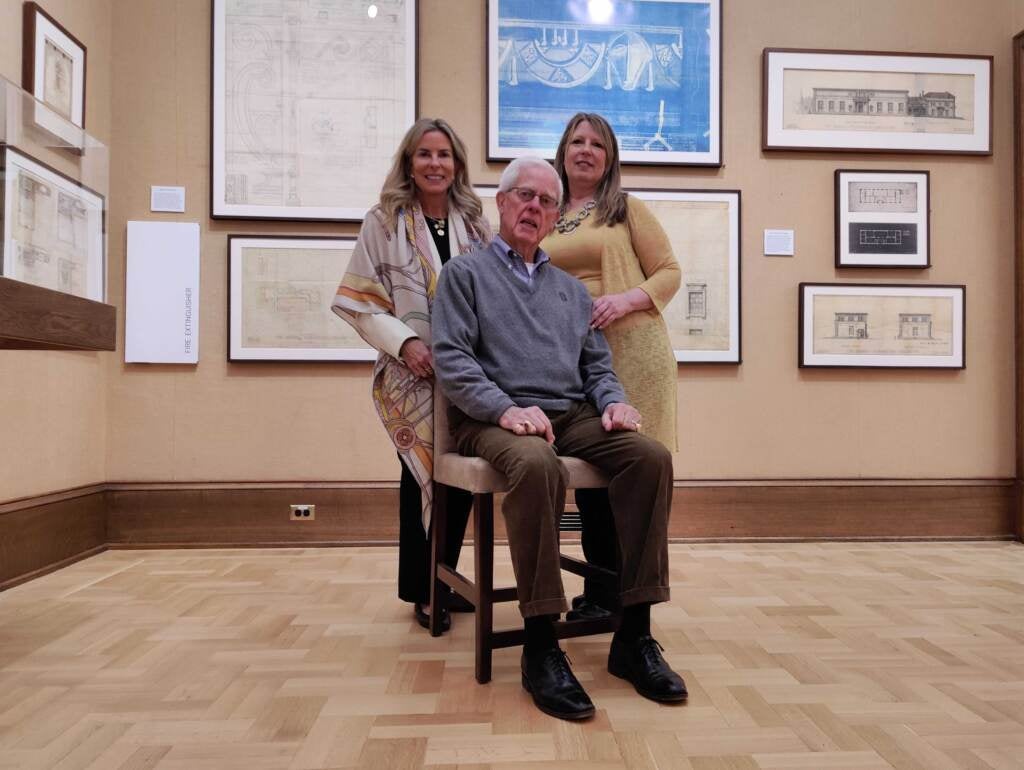

The university’s former president, Father Kevin Gillespie, created a long-term lease of the Barnes building at the urging of Jim Maguire, founder of the Maguire Foundation.

“I said to him: In my opinion there is no decision. We have to have this building as part of the university,” said Maguire. “Art is part of education. To get an education from the perspective of art is very important. We should have it because we’re a first-class university.”

The museum is named after Maguire’s wife, Frances, an artist and philanthropist who to St. Joe’s through the family foundation. Funding for the building renovations came out of that donation. Unfortunately, she did not survive to see the museum completed. Maguire died in 2020 at age 84.

“Today, if she was here, she would be so proud of this because she really appreciated community, neighborhood art museums,” said Meghan Maguire Nicoletti, Frances’ daughter and president and CEO of the Maguire Foundation. “She was very instrumental in bringing art to children, to older people, to people that otherwise might not have access to art.”

The university’s collection spans from 16th-century religious art to new work by contemporary artists, with a particular strength in colonial Latin American art. It is normally hung on walls scattered throughout the St. Joe’s campus. With a new museum, director Emily Hage can show about 500 pieces in one space.

“That’s the thing: It’s a space. It’s a place where people can come together,” said Hage. “It allows us to show this art that scholars know about but a lot of people didn’t. It allows us to have a space for contemporary artists, and there are never too many of those spaces.”

Hage’s goal is to do literally everything.

“That’s my mantra: Art is relevant to everything,” she said, ticking off programs related to a range of tangential interests including a gallery of prosthetic designs for occupational therapy, wall text with students’ poetic responses to art, planned educational programs with Gompers Elementary school across the street, and a robot docent named Pepper powered by artificial intelligence

Pepper is about three feet high with big Manga eyes, a touch screen on its chest, and a child-like voice.

“I am learning to be a docent,” Pepper explained. “My friends here are programming me to talk about art, then interact with museum visitors as part of their research on how artificial intelligence can be more helpful in human-centric spaces.”

The building was originally designed in 1922 by architect Paul Cret specifically to display Albert Barnes’ extensive collection of impressionist and post-impressionist art. The building was arranged as a string of small galleries with parquet hardwood flooring and walls covered in beige burlap, in which Barnes arranged his collection alongside meticulously chosen furniture and metal hardware.

Visitors might recall the spaces could be dim, with some paintings receding into shadow.

The exterior of the building has been repaired and restored, using marble sourced from the same French quarry that supplied the original stone. The African-motif tiling around the entrance remains intact.

The big changes are inside where the gallery walls are now gleaming white and the lighting is modernized, able to automatically adjust according to daylight from the windows. Some of the walls have been removed to enlarge gallery spaces. New hallways between rooms have been added.

The warmth of the original oak trim and soft burlap is gone, except for one gallery where the original interior design preferred by Albert Barnes has been maintained. It now features Cret’s design drawings of the building, and will be used ongoing as space showing artifacts of architectural history.

The renovation created clean, modern lines that highlight the high curves and arches of the ceilings, which principle architect Jamie Unkefer of the design firm DIGSAU said went unnoticed before.

“We wanted to emphasize the volumes of this, that are really an integral part of the design,” said Unkefer. “They’ve been here all along, but I don’t think they were something that was emphasized in the way we now think they are.”

Still intact are the three original arches built into the high wall of the Great Hall, where Henri Matisse famously installed a triptych of abstract dance. Right now they are bare. Hage plans to fill the space with a rotation of commissions from contemporary artists.

Underneath the lunettes, the Great Hall greets visitors with large pieces by Black artist Purvis Young, painted wooden fencing pickets by the female BIPOC artist Lavette Ballard, a 19th century painted tapestry from India by an unknown artist, a painting on corrugated aluminum by the Philadelphia Chicana artist Marta Sanchez, and an 18th century Colonial Mexican painting of the Christian saint Catherina of Alexandria.

Accessibility is the main objective for Hage.

“Starting right out of the block with people associating us with being welcoming,” she said. “That they are represented on the walls, that they have a voice.”

The museum is accessible on the most basic levels, too. The exterior has been installed with a ramp, admission is always free, and all of the wall text labels are printed in both English and Spanish. Hage also points out that wall text is written mostly to avoid art-historical language, with many based on direct quotes from the artist.

Some of the wall text describes art in the words of young people experiencing the museum.

In one of the galleries, the wall text features poetry written by St. Joe’s students. The exhibition features a close-up photograph by Naomieh Jovin of the hands of a Black girl dressed for her First Communion, which student Niyada Birch used as a prompt to remember her own religious experience as a child.

The world can be cruel to me

But my job is to love everybody

I will take this to remember there was a surrender involved

Surrender? When I do, I let go of me.

I let go of who I used to be. I get to feel free.

Mama told me.

“We are a brand new museum. We don’t have to worry about a past,” Hage said. “Thinking about what is being asked of museums right now, thinking about how we can be relevant, we can jump into all of the things that museums have been doing, but can do more of.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.