Southport Marine Terminal back in play

April 6, 2010

By Thomas J. Walsh

For PlanPhilly

The Southport Marine Terminal just might be back on track.

In the next two months, the Philadelphia Regional Port Authority (PRPA) will again seek bidders to develop what could be a $450 million new facility for South Philadelphia. PRPA officials and competitors in the bidding said the project will provide more than 300 well-paying jobs and a major new engine for economic development in the region.

Many state and local real officials seem to link the commencement of the long-awaited and highly controversial dredging process – the deepening of the Delaware River from 40 to 45 feet – to the renewed movement on Southport. Others said Southport would be just one benefit of a deeper river.

Packer Avenue terminal

“A deepening of the navigational channel will benefit the entire tri-state maritime complex,” said Bill McLaughlin, director of governmental and public affairs for the PRPA. “Among the beneficiaries will be the port, because it will mean an expanded capacity for containers. But it would be wrong to say that the deepening of the Delaware was proposed, authorized or encouraged simply because the port of Philadelphia could develop Southport – that’s simply not the case.”

But the dredging is still in a bit of legal limbo. Judge Sue Robinson of the U.S. District Court in Delaware ruled the project could proceed in late January. And while it is now underway in the First State, lawsuits from the state of New Jersey and environmental groups still linger in Federal court, and could bring a halt to the process at some point. Proponents of the deepening interviewed this week expect those lawsuits to be resolved by mid-summer.

There’s also a recent report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office that says market conditions have changed to the point where the necessity of the deepening is again in question (see recent Philadelphia Inquirer story here). McLaughlin counters that the report is just the latest in a string of politically motivated GAO reports, this one commissioned by N.J. Sen. Frank Lautenberg.

Southport and the dredging of the Delaware “are really stand-alone projects,” said James McDermott, the PRPA’s executive director. “But if we did nothing else to develop marine lands in Philadelphia, we need to do this. We have ships now waiting for the tide to come in, so they can make their way up the river.”

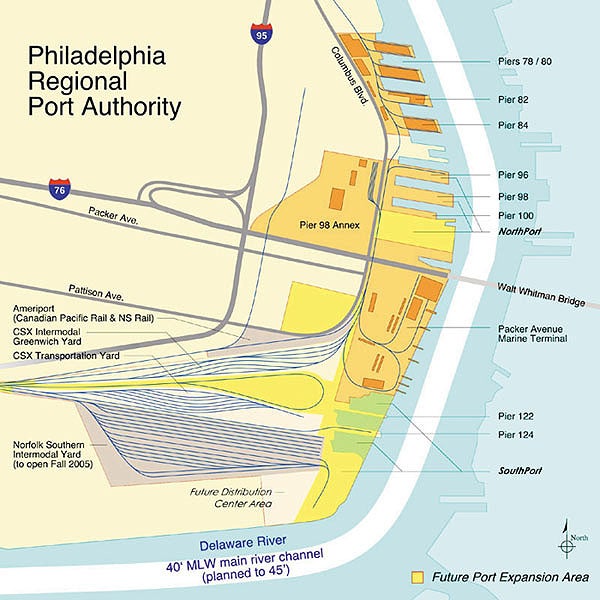

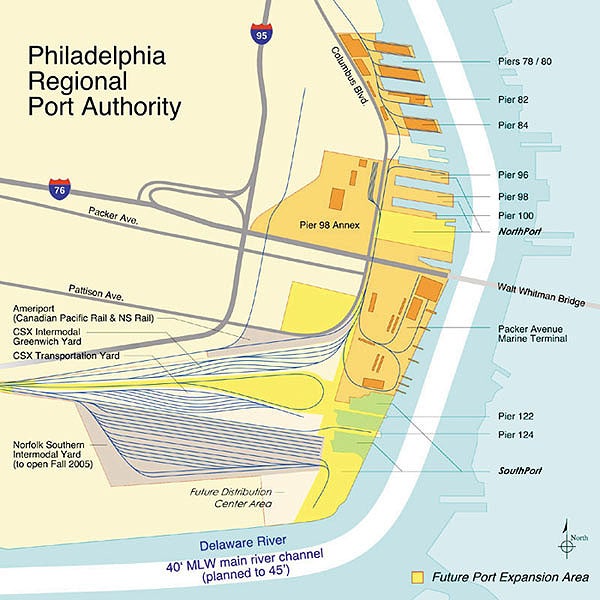

Southport was introduced publicly for the first time during an “information only” presentation to the Philadelphia City Planning Commission in March 2009. The 180-acre site would consolidate several piers just south of the Packer Avenue marine terminal, adjacent to three major rail carriers (Norfolk Southern, CSX and Canadian Pacific) and Interstate 95. It would also marry a sizable chunk of the eastern Navy Yard – 100 or more acres.

At the Planning Commission meeting 13 months ago, Kate McNamara, a special assistant to Gov. Ed Rendell for maritime activities in Southeastern Pennsylvania, said, “Most of the proposers say they’d like to see a 45-foot channel in order to make the project viable.”

Re-trenching

“I think in effect it was” the dredging that got the project in motion again, said John Grady, senior vice president of real estate services at the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corp. (PIDC). “The shipping community needs to see that before you could reasonably propose a significant expansion of the port facilities.”

Southport is something that “over the years has kind of evolved,” Grady said. “We’ve committed about 100 acres of land at the far east end of the Navy Yard to the state to support them in their RFP (request for proposals) process.”

That process got started about a year ago, not long after McNamara’s presentation. But because of the horrid state of the capital markets and the overall economy, combined with the fact that dredging was still up in the air, the timing was less than ideal. “The state has re-trenched,” Grady said. “We’ve agreed on behalf of the city that we would give the land at no cost to the Commonwealth, and the Commonwealth will fund the infrastructure and site improvements necessary to support the project.”

Rendell’s office has stated it will kick in $25 million for major infrastructure and site clearance work.

Sources at the state level said the environmental permitting process is underway for, among other things, the demolition of the long-derelict family housing (the old Mustin Field homes) at the Navy Yard – the land Grady was referring to. Riparian issues are also being sorted out, along with environmental factors ranging from underground toxins to the nest of bald eagles discovered a few years ago. The stated goal is to release the new RFP this month, but a more realistic time-frame is sometime before the end of the second quarter (June 30), the PRPA executives said.

In past years, there has been additional legal wrangling over who owns the 100 acres that PIDC is committing – the city or the state. According to the city, the land is owned by the same entity that owns much of the rest of the 1,200-acre Navy Yard – the Philadelphia Authority for Industrial Development (PAID), which is the finance and bond-issuance arm of PIDC. At issue is a total of 200 or more acres of the eastern Navy Yard, which was said to be deeded to the city after the Navy closed the base a decade ago. Some say the land is state-owned, and there’s now a bill in the state legislature to declare that part of the Navy Yard as state property.

Part of the plan

“We’re very supportive of the Southport idea, although there have been no specific actions that the commission has had to take at this point,” said Gary Jastrzab, deputy executive director of the Philadelphia City Planning Commission. “And generally speaking, the economic development brain trust of the city believes that the dredging is good for the city, and on the face of it, having a bigger channel means bigger ships.”

The development of Southport is literally part and parcel of the Planning Commission’s long-term vision for that area of South Philadelphia.

“As part of our 2035 Plan, we are doing a district plan for that area – the sports complex, the airport, and the Navy Yard,” said Jastrzab. “It is one of the districts that we have defined for the comprehensive planning process. It’s very specialized. I don’t think the channel dredging is really going to affect the land side very much. It’s a working river, and we want it to remain that way.”

Where the river meets the rail

The key word is “intermodal,” specifically in this case, ships, trucks and trains. CSX has its own intermodal facility that terminates at the river and the Packer Avenue terminal. PIDC dedicated about 135 acres to Norfolk Southern, which expanded and built the first phase of their intermodal yard (adjacent to CSX). Where the two rail facilities come together is the point at which Southport would be built.

“Historically, Philadelphia’s been a little bit of a niche container terminal,” Grady said. “We attract about 200,000 containers a year.” Fruit and other perishables from Chile and other South American countries, cocoa beans, U.S. military supplies headed to Iraq and Afghanistan, oil and fuel supplies, cement products and plywood are some of the bigger sources of revenue for the area’s ports. But bigger markets like New York get about six million containers per year, he said, and Long Beach, Calif., the largest port in the nation, takes in some 10 million containers annually. “So the opportunity to help grow that business and attract more investment in the shipping lines is something that we hope the market reacts well to.”

“I think the promise of Southport has a lot of things going for it,” said Robert Palaima, president of Delaware River Stevedores, Inc. (DRS), which operates the Tioga Marine Terminal further north on the Delaware. “You’re south of all the bridges, you’re adjacent to three class one rail lines, which is unique. And then of course with the river deepening project, that at least gets you in the game. Looking at the expansion of the Panama Canal in 2014 or so, and if the cycle turns and the worldwide economy starts booming and trade increases, then yeah, I definitely think it’s viable.”

Palaima

Asked if Southport would happen without the dredging, Palaima didn’t hesitate. “Probably not,” he said. “I think that was a sine qua non.”

DRS was one of four initial bidders on the Southport project. Palaima said he’s not sure yet if they’ll be back in the competition. DRS is owned jointly by Seattle-based SSA Marine (itself a unit of holding company Carrix and their partner Goldman Sachs) and Ports America Group, based in Iselin, N.J.

“We haven’t seen the documents yet,” he said. “I think there are some strange circumstances as to what may be available, and the parameters of what’s being asked for submission. Generally speaking, we of course would be interested, but how we respond will depend on our parent company.”

The state has engaged the audit firm KPMG as a consultant to review the coming RFQ (request for qualifications) and RFP.

Fair share of market share

All of those interviewed for this story agree that the port of Philadelphia (and Camden as well) has its limitations. First and foremost, they said, is its location 100 miles upriver from the Atlantic Ocean. Second, even a river deepened to 45 feet wouldn’t accommodate most new ships, which require more than 50 feet of clearance. As for the bottom line, they concede that the port will never compete with New York, Norfolk or Long Beach, but it can add to its niche by taking advantage of crowded conditions and higher prices elsewhere.

“The advantage that the port of Philadelphia finds itself in at this moment, especially compared to other ports in the northeast [region of the U.S.], is the availability of land, particularly land adjacent to and south of the Packer Avenue marine terminal and the Walt Whitman Bridge,” said McLaughlin.

Philadelphia’s Port has the advantage of available space.

“We are working now to resolve what the footprint ultimately will be,” he continued. “We have this opportunity to expand, particularly our container capacity. As the dredging moves forward, [it becomes] more attractive to a steamship line – hopefully, especially an Asian line.”

McLaughlin said Philadelphia desires an entrée into the Asian market because of that market’s rapid growth. Philadelphia has a good shot at attracting an Asian line, he said, because major ports in New Jersey, New York and Virginia are fairly bursting at the seams.

“Steamship lines look forward in large swaths of time,” he said. “They are confident that there will be an upsurge in the global economy, with an upswing in international trade. The Asian market is huge, and has been centered almost exclusively on the West Coast.”

The multi-billion dollar expansion of the Panama Canal might change that, he added.

“Asian carriers will be looking for alternative East Coast ports of call,” McLaughlin said. “Philadelphia makes a lot of sense because we’ll be able to offer almost an exclusive marine terminal for one particular steamship line if it comes to that.

“We’re within the proximity of the greater New York metropolitan area – only 90 miles away. There’s the access to the three tier-one railroads, and to the major highway. And our labor is more reasonable. So we’ve become more attractive.” This threat of competition from Philadelphia is the real reason that New Jersey politicians have consistently opposed the river deepeining for 20 years or more, McLaughlin contends.

But the deepening would also help shipping in parts of New Jersey, especially since there is a new project from the South Jersey Port Corp., at Paulsboro (across the river from the Philadelphia International Airport). It’s a 175-acre cargo terminal scheduled to open in 2012.

Of course, the story takes on varying hues, depending on the teller of the tale. Not that it’s complex, or anything. The only interested bodies involved are three state governments; a new governor in New Jersey and one in his final year in office in Pennsylvania; practically every city agency in Philadelphia; quasi-public entities such as PIDC; environmental activists and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; unions, notably the International Longshoremen’s Association; the U.S. Government Accountability Office; the Army Corps of Engineers; the alphabet soup of port authorities on both sides of the river and a myriad of other shipping concerns.

Palaima, for his part, seemed cautiously optimistic. “I don’t think that people are operating with that sense of impending doom that they were a year ago, but it’s still pretty rough out there in the capital markets,” he said. “Last year, you had an unprecedented, generational sea change in what was happening in world shipping.”

Jastrzab said he’s been informed that Rendell’s office and PIDC will soon be back in front of the Planning Commission at a monthly public meeting, with more detailed and revised Southport plans – possibly as soon as May.

“I think things are going very well,” said McDermott, who predicts 340 fulltime jobs, in addition to multi-year, phased construction work. “Fortunately for us, in the Rendell administration, we are seen as a significant economic engine.”

Contact the reporter at ThomasWalsh1@gmail.com.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.