Sought after diaries from the 19th century offer a glimpse of a life long gone in Northwest Philly

When historian Mark Frazier Lloyd knocked on John Harris, Jr.’s Chestnut Hill door to inquire about Harris’ grandfather’s 19th-century Germantown diaries, Harris claimed he didn’t know anything about the diaries. And even if he had, it wouldn’t be polite to say so.

“It was not considered proper to open somebody’s diary until all the grandchildren were dead,” Lloyd said of his years-long search for the volumes, during NewsWorks‘ recent visit to the University of Pennsylvania’s Archives and Record Center.

Lloyd, a former president of the Ebenezer Maxwell Mansion museum and a former director of the Germantown Historical Society, moved to Tulpehocken Street in Germantown from Illinois in 1965, when he was 13 years old.

The search that brought him to Harris’ door began when he discovered the work of Penn English professor Cornelius Weygandt (1871-1957) at Penn Archives, where Lloyd has been director since 1984.

In his 1946 autobiography, Weygandt mentioned diaries that his father, also named Cornelius Weygandt, had kept while raising his family in Germantown in the late 1800s.

“I knew right away that I had to have those diaries,” Lloyd said.

The search begins

He began researching the family and found the Weygandt who published his autobiography had a married sister who lived on Walnut Lane. Her son, a chemistry PhD and noted Wissahickon historian, was Chestnut Hill’s John Harris Jr., but the trail went cold there.

Then, in the late 1980s, Lloyd read about a retiring Penn professor of electrical engineering: “and by gum, his name was Cornelius Weygandt.” He had found another of the original diarist’s grandsons.

“I think Professor Weygandt was taken aback by how much I knew about his family,” Lloyd said of their first meeting in a Penn faculty club. “But he took a liking to me.”

Professor Weygandt had a sister named Ann, a University of Delaware English professor who had the diaries.

It took a few weeks, but she called Lloyd back and in 1992, she donated her grandfather’s diaries, spanning almost 60 years from 1848 to 1907, to the University of Pennsylvania.

The diaries would continue to stay shut for years. “She insisted the diaries not be opened until she and her brother were gone,” Lloyd said. Ann’s brother, the electrical engineer, died in 2004 (five days short of his 100th birthday), and she died two years later at the age of 96.

A vivid portrait of a Germantown family

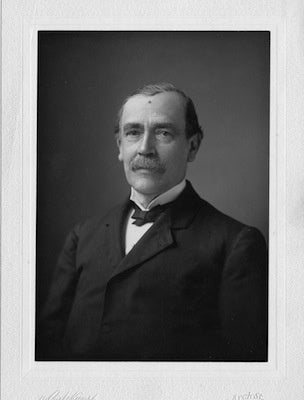

Their grandfather, diarist Cornelius Weygandt (1832-1907), worked all his life at a bank that stood at 4th and Chestnut streets. His meticulous daily diaries chronicle not just Germantown’s Victorian society, but a colorful parade of artists and architects like Cecilia Beaux, Thomas Eakins and Frank Furness.

“The window on Victorian-era Philadelphia [Weygandt] created is both rare and historically significant,” Lloyd said.

After buying up seven outstanding volumes that escaped Ann Weygandt’s collection, Lloyd admitted there are still a few missing.

So did the family hide or destroy them?

“I think that’s unlikely, considering what remains,” Lloyd explained, because the surviving content is so “sensational.”

Today, as Lloyd put it, Weygandt’s packed pages of minute cursive writing are “stunningly difficult to read,” but with a little patience, the old-fashioned lines make a vivid portrait of a Germantown family.

On New Year’s Day 1895, Weygandt wakes up to “a beautifully clear bright morning” and eats breakfast with his wife, Lucy, and his 24-year-old son, Cornelius, nicknamed “Corney,” who lived at home while working as a journalist at the Evening Telegraph (later, he was the Penn author who first caught Lloyd’s eye).

The family lunches on ham and chafed oysters (Cornelius himself cooking them at table), Corney goes sleighing on the Limekiln Turnpike, and Weygandt takes a walk, enjoying “the keen dry air, and the rather ticklish walking over the icy surface of the snow.”

Dinner is soup, roast turkeys (which Corney refuses to carve), oysters on the half-shell, plum pudding and ice cream. Later, Weygandt notes, “I was obliged to steal away to the water closet three times…caused by I know not what.” Next month, Corney comes down with a fever, and Lucy sleeps in a lounge at the foot of his bed until the young man recovers.

The founding of Germantown Historical Society

Mt. Airy native Jim Duffin, the Center’s senior archivist, was the first professional historian to dive into the diaries, as part of his research for an article about the founding of the Germantown Historical Society in 1900.

Weygandt was a founding member, and Duffin knew the diaries would provide lively insight.

According to the archivist, “Weygandt was apparently the one to suggest the society should have men and women members, but I don’t think the minutes mention that.”

While Weygandt was conservative, Duffin insisted that for his time, he wasn’t “reactionary.” He may not have believed in women’s suffrage, but his daughter did join the first class of Bryn Mawr College when it was founded in 1885.

“He might interact with African Americans or Irish servants, but you can tell he never thought of them as his equals,” Lloyd added. When servants who were not part of the family lived alongside you, “there were rules and protocols that everyone followed to keep a sense of propriety about it all.”

The breakdown of those protocols populate some of the more scandalous pages of the diaries, and thanks to Maxwell Mansion, the details have gone public with a blog featuring excerpts.

“You can really understand the locations if you’re from the Northwest,” Duffin said. Readers will also enjoy seeing that many things don’t change: the diaries follow the fates of the husbands, wives, children and workers caught up in the neighborhood gossip, and, as Lloyd put it, “the tug-of-war between self-interest and altruism.”

“It is simultaneously antique and modern,” Lloyd said of nineteenth-century Germantown. “The emotions that Weygandt describes as motivating people are timeless.”

Maxwell’s latest Weygandt excerpt can be found at the Ebenezer Maxwell Mansion blog.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.