The slow climb to historic district status

Jan. 6, 2010

By Alan Jaffe

For PlanPhilly

The designation of a Philadelphia neighborhood as a historic district is a cherished and increasingly valued honor. It places the community under the protection of the city’s Historical Commission to prevent alterations that would harm the historic or architectural character of its buildings. Here and in other cities, the designation has helped increase property values. It also fuels civic pride, instills a sense of the past, and helps ensure the future of each neighborhood.

Between 1983 and 2003, the city designated 10 historic districts. The first was Main Street Manayunk, with 471 properties (the totals include condominium units). The largest was Rittenhouse-Fitler, with 5,828 properties.

Stained glass mix in Rittenhouse-Fitler Square

But since the designation of the Old City district, with 3,225 properties, in 2003, only three nominations have been approved. Four neighborhoods have filed nominations, including one that has been waiting for approval since 2002. Another community has been working on its nomination since the late 1990s.

Size matters

The long waiting periods are all about size: the size of the proposed districts and the size of the staff that has to administer them.

“Anyone can propose the designation of an individual site or historic district,” explained Jonathan Farnham, executive director of the Philadelphia Historical Commission. Any city resident, or non-resident, can nominate an individual site or district, and the property owner’s consent is not needed.

Historical Commission staff can also nominate for designation. “Due to staffing and budget constraints, the commission itself has done very little in the way of nominating historic resources in the last six years,” Farnham said. “There was a time when the commission had the luxury of producing nominations on a regular basis. That has not happened in several years, except for a few occasions.”

The commission is one of the few city departments that have not suffered budget cuts over the past year. But that’s because of “a recognition on the part of the administration that the Historical Commission has been historically funded at levels lower than those of other comparable agencies in comparable cities,” Farnham said.

The commission has six full-time staffers: the director, a secretary, and four historic preservation planners. A seventh planner is funded by the Office of Housing and Community Development to conduct federal historic preservation reviews for HUD projects.

The staff size and the increasing workload sparked by historic designation reached a critical juncture in 2003, following the designation of the Old City district. Historical Commission members appointed by then-Mayor John Street decided the staff was unable to administer any additional large districts. “In the mid-1990s, the commission was reviewing about 600 building permit applications for historic sites,” Farnham explained. “By 2003, it had more than doubled, to about 1,300, and the staff size had stayed completely flat. The Historic Preservation Ordinance requires the commission to process building permit applications within a specific amount of time. That same ordinance does not provide any timeliness for designations. As the permit application review workload got larger, the commission shifted more of its staff from other efforts, including designation, to building permit applications. By 2004 to 2007, the peak of the real estate market, the commission was reviewing approximately 1,500 applications a year, with the same staff it had been reviewing 600 in 1996.”

Technological and market shifts

The commission announced it would not review any new district nominations until it found a way to operate more efficiently or its budget was increased. “We made an argument fairly cogently that we needed to be better funded. I think that Mayor Nutter was convinced of that, but 16 months ago he was hit with the worst economic crisis in decades,” Farnham said. “So we pulled back from that.”

Changes in some regulations that give staff members more authority to approve building permit applications has helped increase efficiency. Changes in technology also have helped the process. Alternate materials for replacement, such as aluminum-clad windows for wood trim, are now considered in compliance with standards set by the U.S. Secretary of Interior.

“With both the slowdown in the real estate market and a series of efforts to streamline the office beginning a little over a year ago, the commission started talking again about restarting its historic designation program,” Farnham said.

Last October, the commission approved the designation of the Tudor East Falls district, with its 210 properties. In December, the stately Parkside district, with 110 properties, was approved.

Awbury Arboretum, with just 29 properties, has been working on designation since 2006. Farnham predicts the commission will act on that nomination at its March meeting.

Many of the individual properties in Awbury are already on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places, explained resident Mark Sellers, but research has shown that Awbury was “a single aesthetic whole, a single-family compound” that evolved from the 1850s to 1920s. The community has remained largely intact, but its zoning leaves open the possibility that “some developer could show up and say, ‘I’d like to put a five-story apartment building here,’” Sellers said.

“As property values decline, people let their historic properties go. They can’t afford to fix the roof, or do this and that. Something collapses and they just leave it on the ground. But when property values are climbing, you have a different sort of problem, which is that somebody says, ‘I think it would be great to put an in-ground swimming pool here,’ or some other insensitive, inappropriate piece of construction there,” Sellers said.

“The historic district will send a message that the community wants to send, which is that development is over at Awbury.”

Historic district designation also says “we value the way our neighborhood looks and we don’t want it to change,” Sellers said. Awbury has “always had a very clear identity and a strong community pride in our history.”

The distinctive houses of Awbury Arboretum are expected to be designated a historic district in March.

The four-year wait for district designation hasn’t been easy, but Sellers said there has been an upside. There has been recent scholarship about Awbury that will be incorporated into nomination, he said. “We recognize that the nomination document is going to be used and looked at, and we want it to be as good and accurate as it can possibly be.”

In addition to Awbury, action is also expected to pick up on the nominations of the one-block, 26-property East Logan neighborhood, which filed its nomination last May, and the sprawling, 800-property Overbrook Farms community, which has been working for approval since 2004.

“Overbrook Farms is a medium-sized district, and we need to start to think about the impact of districts like that on our yearly permit application numbers,” Farnham said.

“With the streamlining we’ve done, we think we can probably handle Overbrook Farms.” The commission hopes to secure funding from the Fels Foundation, through the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia, to hire a couple of graduate students in the summer to help complete the Overbrook Farms nomination, and process it next fall.

The Historical Commission hopes to approve the nomination of the 800-property Overbrook Farms district in the fall.

Historic designation is an important goal of the 118-year-old Overbrook Farms Club, explained organization president Terry Henry. “We struggle with preserving the character of the community as we deal with the challenges of modernity and the needs of modern families,” he said. The creation of the planned suburban community on the Pennsylvania Railroad line was “unique at the time. Maintaining that character of the homes and the community itself is very important.”

Henry said he understands the challenges faced by the Historical Commission, but every month brings changes to the fabric of Overbrook Farms. “Shortly after our application was submitted, two properties came down because of poor upkeep. We can’t tie that to not having the designation, but it highlights an issue we’re dealing with. Once we have the designation, it may help bolster property values and make the neighborhood more attractive to other folks.”

Review and enforcement

For the Historical Commission staff, district designation is “just the beginning of the work,” Farnham explained. Any proposal that would alter the exterior appearance of any property listed on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places, and any change that requires a building permit, must be reviewed by the commission before work can begin.

“There is also, sadly, a fair amount of enforcement, because there are some property owners who work without building permits and without Historical Commission review. We’ve tried to step up our enforcement, but we don’t have adequate staff to constantly be inspecting properties in the field.” The commission relies on the army of inspectors in the Department of Licenses and Inspections for enforcement, but that department’s numbers have been cut by the city budget problems.

“Probably the most important component of our enforcement is the people in the neighborhood who are interested in the preservation of our historic communities,” Farnham said. “We react to complaint calls on a very regular basis from neighbors.”

Garrett-Dunn House before fire totally destroyed it.

If work is performed illegally, or if a property is allowed to deteriorate to a point of “demolition by neglect,” L&I issues violation notices. If the owner doesn’t comply, the commission turns to the courts.

“We’ve tried to go after the worst of the worst offenders much more aggressively over the last two years or so,” Farnham said. “We’ve tried to keep a watch list of the worst offenders and asked a judge in the Court of Common Pleas to order them to bring the property in compliance. That’s been successful in a handful of cases, but it’s incredibly time-consuming for the staff here and for the city attorneys.”

Opposing forces

The typical nomination for a historic district in recent years has sprung from concerned neighborhood organizations or grassroots groups working with the Preservation Alliance, which has sought grant money to help fund nominations. The Historical Commission staff members serve as consultants in the process. In Old City, the civic association promoted the nomination. In Parkside, the Preservation Alliance worked in collaboration with the Parkside Historic Preservation Corporation.

In Tudor East Falls, a group of about a dozen residents “rallied together to do the work themselves, to do the research, to write the statement of significance, to do all the work surveying the neighborhood to understand what properties were there, and the types of properties to photograph,” Farnham said.

That community also had its adamant opponents. “Many of those who were opposed simply did not understand the process and the implications of designation,” Farnham said. “Once we had the opportunity to educate them about that, I wouldn’t say their opposition disappeared, but for the most part they begrudgingly accepted the designation.”

Opposition usually stems from concerns about infringement on the owners’ private property. “We remind them that the city of Philadelphia has had zoning codes and regulations for over 80 years, and their properties are very closely regulated already,” Farnham said. The individual property owner, in most cases, will have to deal with a commission review once in 10 to 20 years, for a permit to change windows, repair a roof, or add a deck. “So I don’t think they have too much to fear from us.”

In the case of Parkside, rather than opposition, the commission had to respond to a group of neighbors outside the proposed boundaries who wanted to be included in the historic district. “I think that, too, came from some misunderstandings of what designation would bring. There was some assumption that it would bring a series of grants and tax breaks and other government subsidies, which can be the case. But not very often is it the case with single-family residences, which most of those were.”

Future historic districts

Despite the increasing workload, and little hope for increased funding in the near term, the Historical Commission continues to encourage appropriate neighborhoods to seek historic district designation.

“I think we try to be realistic with the community groups and don’t want them to be disappointed if their districts are not created within months or even a year or two,” Farnham said. “We make it very clear to them that this will be a long-term process – that it cold be five or as many as 10 years before they achieve their goal of designation.”

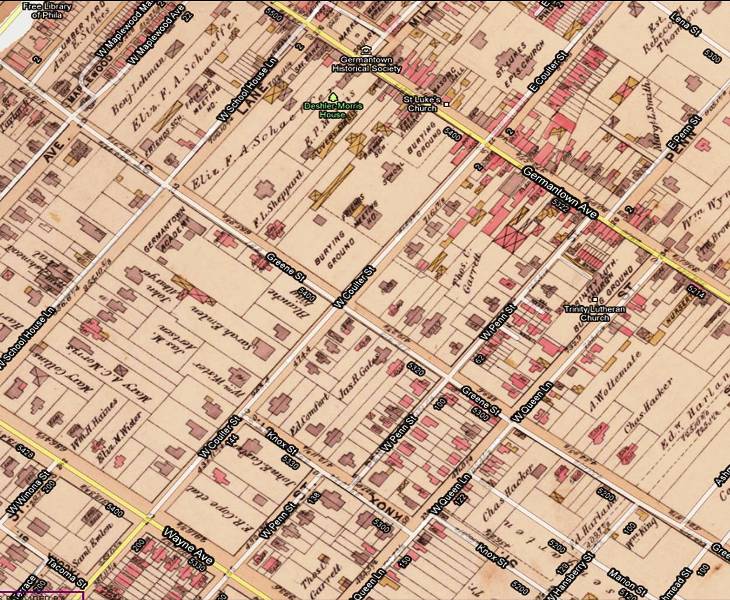

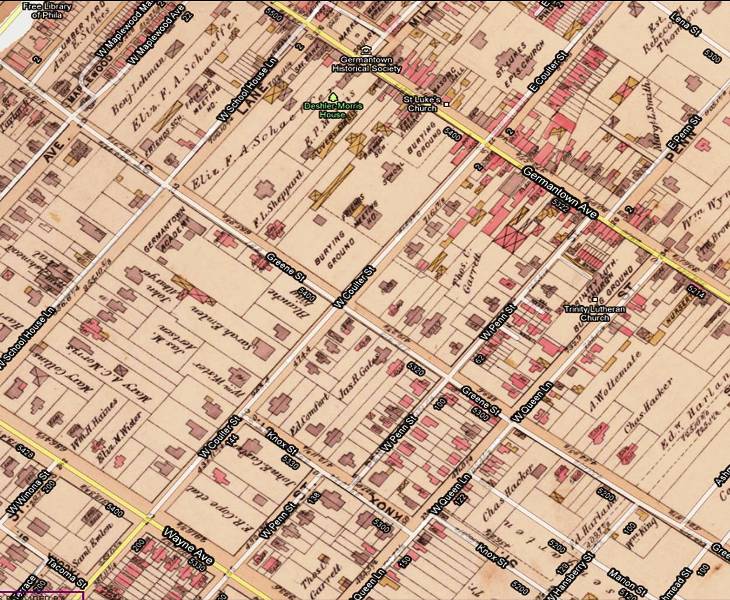

The Penn Knox neighborhood in Germantown first submitted its nomination in the late 1990s, and it was reviewed by the commission staff with neighborhood representatives about five years ago. “At that time the neighborhood people indicated they were were interested in updating and resubmitting it, but we haven’t received anything at this point. And the commission does not really have the staff to take that task on.”

Nominations are also in the works for Tacony-Disston, the company town of 1,030 properties that was built around the famed saw manufacturer, and Washington Square West, a wide swath of 1,673 properties. “We’ve spent a lot of time with the people in Washington Square West to help them manage their expectations,” Farnham said.

And before the Historical Commission can justify approving a district the size of Washington Square West, “we would have to reconcile with the people in Spruce Hill.”

The proposed Spruce Hill district is made up of about 2,000 properties and extends from Market Street to Woodland Avenue, from 40th to 49th Street, “a big wedge of pie taking a large part of West Philadelphia,” as Farnham described it.

Aside from Penn Knox, the advocates for Spruce Hill’s designation have been waiting the longest.

“The district nomination there was created at a different time,” Farnham said. It was planned in the heyday of the commission’s historic district program, “before the commission had reconciled itself to the fact that every designation was going to produce a certain amount of building permit applications, and every one of them was going to have to be reviewed by a staff member. There was a time in the late 1990s when the commission really had failed to come to terms with that and was pushing for larger and larger historic districts.

“Spruce Hill, as it is imagined, is very large, and not homogenous, not cohesive. So I think one of the proposals we might have for the commission is that the district be broken down into a series of smaller districts that would have tighter, more justifiable boundaries and would encapsulate shorter spans of history.”

The southeast corner of Spruce Hill has a concentration of Italianate buildings dating to the mid-1800s. A concentration of High Victorian buildings could be sliced off into another, smaller district.

The Spruce Hill residents are the constituents of Councilwoman Jannie Blackwell, who raised questions about the historic designation process in 2004. She proposed an amendment to the Historic Preservation Ordinance that would shift power back to City Council. It was never signed into law, but Blackwell’s concerns about the cost of designation to low- and moderate-income residents resulted in changes to the commission’s regulations and the creation of the Historic Home Repair Program, which helps fund repairs to historically significant residences.

“Much of her concerns for her constituents have been addressed,” Farnham said. “But before we do anything with her district, we need to work carefully with her.”

The series of public meetings that followed Blackwell’s campaign was “an interesting eight months or so for the Historical Commission,” Farnham said. “We learned quite a bit from that.”

Contact the writer at alanjaffe@mac.com.

Designated Historic Districts

Main Street Manayunk, designated 1983, 471 properties

Diamond Street, 1986, 240 properties

Park Mall, 1990, 19 properties

Rittenhouse-Fitler, 1995, 5,828 properties

Historic Street Paving (the only thematic district), 1998, 325 blocks

Society Hill, 1999, 3,403 properties

Girard Estate, 1999, 487 properties

FDR Park, 2000, 1 property

Spring Garden, 2001, 2,205 properties

Old City, 2003, 3,225 properties

Greenbelt Knoll, 2006, 20 properties

Tudor East Falls, 2009, 210 properties

Parkside, 2009, 110 properties

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.