SEPTA considering suicide prevention barriers for City Hall Station subway platforms

Thirteen. It’s a number to avoid. Thirteen is bad luck.

For SEPTA, thirteen is worse than that. In five of the last six years, 13 people died after being hit by a SEPTA train. That one anomaly: 2015, when 12 died.

Some of the deaths are accidents. Most are suicides, around 63 percent since 2011. So far this year, there have been seven deaths, five of which were deemed suicides.

For the last few years, SEPTA has run an annual campaign to urge its customers and the public at large to stay safe around trains, in the hopes of reducing those morbid numbers.

SEPTA trains, especially regional rail, move with deceptive speed and surprising near silence. People who might be crossing the tracks as part of an illegal shortcut might not see or hear the train until it’s nearly too late. If they are listening to headphones—especially the noise-canceling kind—they might never realize the rapid approach of certain death. Even a train that slams the breaks can cover a few hundred yards in a matter of seconds before it comes to a full stop.

In an effort to prevent people from walking on or along the tracks, SEPTA has put up fences and posted warnings. When train engineers see someone trespassing, they report it in, said SEPTA General Manager Jeff Knueppel, and a crew gets dispatched to repair fences or put up more signs in an effort to stop future trespassing.

The number of trespassing accidents has declined, said Knueppel. “What we are seeing though is we are getting the right-of-way issues, we’re kind of doing well with them, but the suicide situation seems to be getting worse.”

Regional Rail has seen the most tragedy: 49 fatalities since 2011. Another 14 died on the Broad Street Line and 10 on the Market Frankford Line.

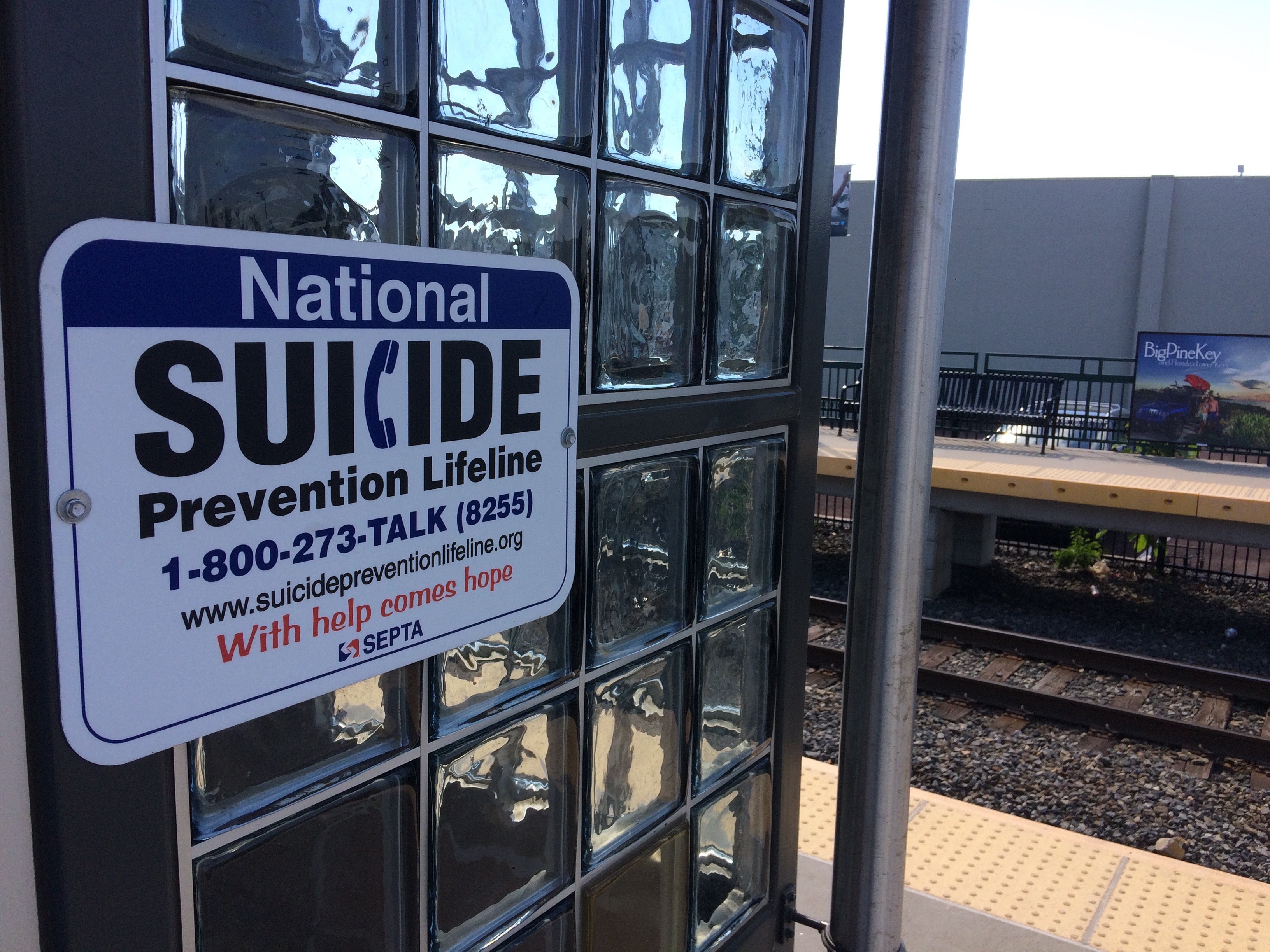

To try to dissuade suicides, SEPTA placed signs for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at all its Regional Rail, subway and El stations.

It isn’t clear if just seeing a sign can actually prevent a suicide attempt. But that doesn’t mean they’re pointless. The signs have led to an uptick in calls to the hotline in Montgomery County, where they were first put up, said Knueppel.

The signs can also help the public realize that train platforms are places where some go to kill themselves, said Jonathan Singer, a professor at Loyola University Chicago and Secretary of the American Association of Suicidology.

Singer said that SEPTA passengers shouldn’t be afraid to speak up if they see someone who looks upset and may be standing too close to the platform edge. “If you’re at a train station and you see someone that seems distraught, maybe looking and peering into the tracks, giving some indication they might jump, the first thing to do is to start talking to them,” said Singer. “‘Hey, how you doing, how about that game last night?’ Anything that can engage them.”

According to Singer, you don’t have to be a therapist, just a friendly stranger. If that person offers they were having suicidal thoughts, that’s what the prevention hotline number is for.

There is one sure bet to prevent suicides, said Singer: Barriers. “Having a barrier literally prevents somebody from killing themselves at that spot.”

Would-be jumpers usually don’t engage in method substitution, said Singer, meaning they aren’t likely to make an attempt by some other means if they are stopped.

That’s because suicide is often an impulsive act. Singer pointed to data showing that those who die by suicide on railroad rights-of-way were significantly more likely to live close to the railway and significantly less likely to have access to a gun, the most common means of suicide in the US. Ease of access to a physically easy means of death — where the act itself is simple, like pulling a trigger or leaning over — means the person is more likely to give in to the impulse.

Singer pointed to the significant reduction of deaths when barriers have been built on brides or ledges, like the Muenster Terrace in Bern, Switzerland, and the reduction of suicides by suffocation in the United Kingdom when coal gas stoves fell out of use.

Knueppel said he asked SEPTA’s engineers to consider platform barriers as part of City Hall Station’s ongoing renovation. The walls would separate the platform from the tracks and would feature automatic glass doors, which would open when the train arrived. Some subway stations in London and Tokyo now have those barriers, as to some tramways used at U.S. airports.

SEPTA doesn’t know yet whether or not it can make the barriers work in the cramped station. But, if it can, it will likely be the first transit agency in the United States to deploy the barriers. And, Singer hopes, the first of many to come to SEPTA’s stations.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.