Sculptor Ned Smyth re-interprets classical architecture using stones

Ned Smyth’s journey toward becoming a sculptor reached a critical juncture in 1971. As a long-haired 23-year-old hitch-hiking from Colorado to New York, he was picked up on Route 9W in New Jersey by Postminimalist neon artist Keith Sonnier and saxophonist Dickie Landry, who played for Phillip Glass. The drivers dropped him off on West Broadway but it wasn’t the last they’d see of him.

In need of a job, Smyth saw an ad for waiters and bus boys in a Prince Street window. He walked in to apply, and the owner, Carol Gooden, asked, “Can you chop and boil vegetables?” With a nod he was made chef.

The restaurant, Food, was run and staffed by artists. Gooden was the partner of artist Gordon Matta-Clark, and Food become a gathering place for the likes of Robert Rauschenberg, the Mabou Mines theater company, Phillip Glass musicians, and Sonnier and Landry, as well as artists of the 112 Green Street Gallery—an artist-run nonprofit founded by Clark where experimental sculptors, painters, dancers and musicians collaborated. This, says Smyth, was his art education.

The friendship with Clark blossomed over a shared fascination with “an-architecture”—or architecture cut out. With Clark as a mentor, Smyth would break into abandoned buildings in the South Bronx, hauling power tools and a generator, and cut large, geometrically shaped pieces out of walls and floors, photographing their excavations into the urban landscape.

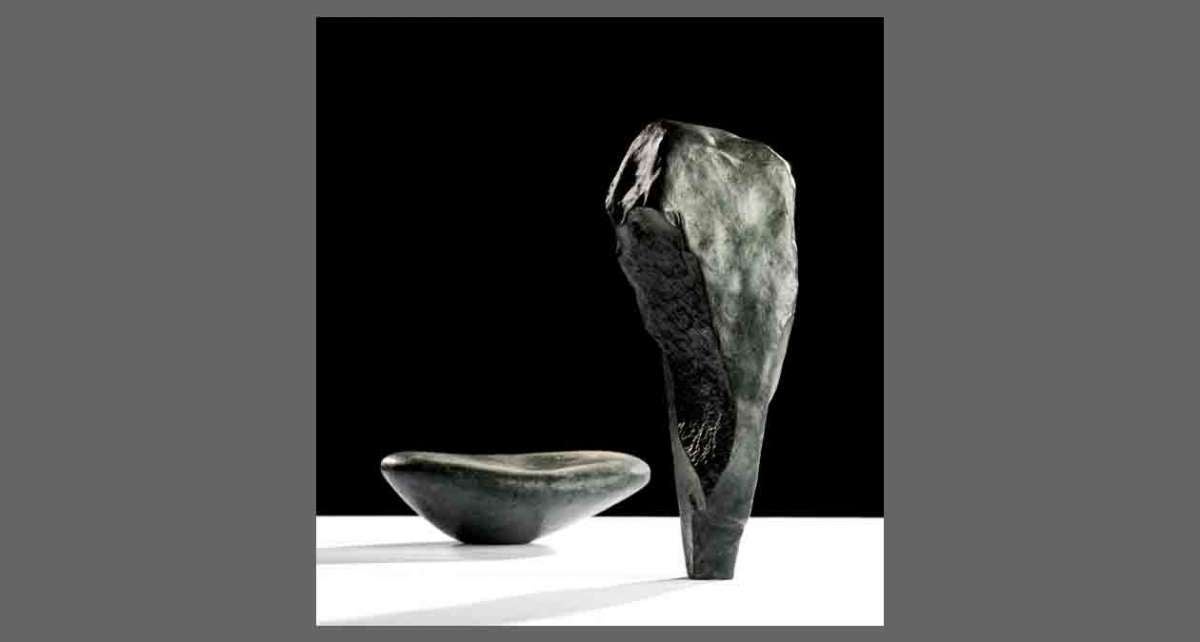

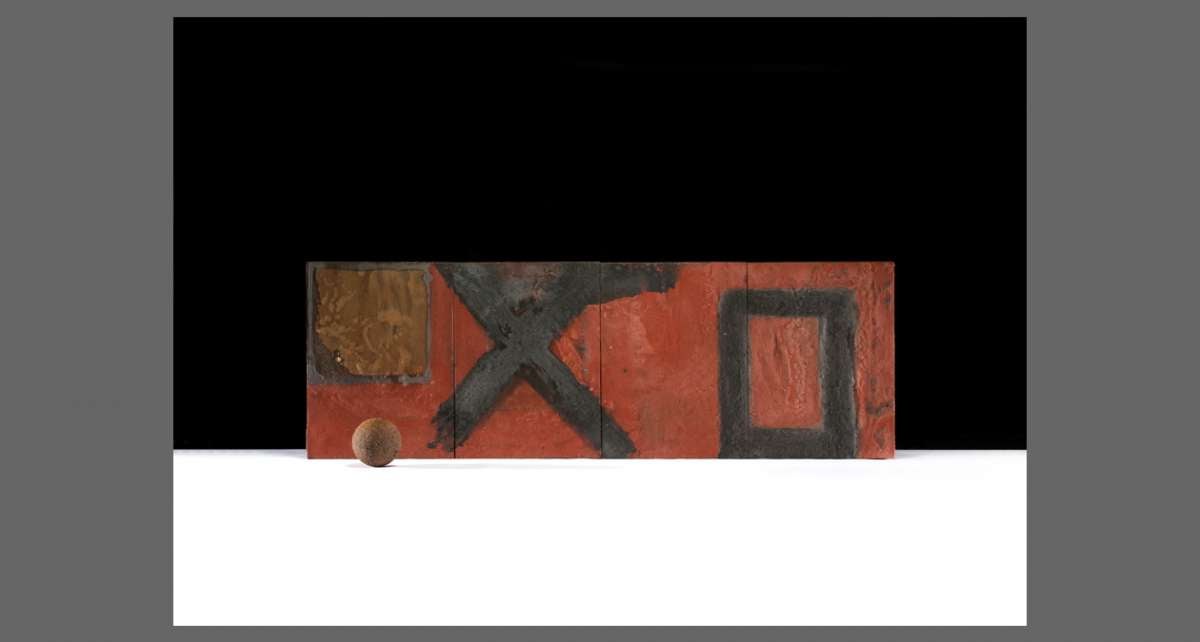

Ned Smyth: Moments of Matter is on view at Grounds For Sculpture through April 2 and includes stone sculpture, stone collections and assemblages, manufactured stone forms, as well as drawings of stones and large-format photographs of stone—in short, everything an artist can do with stone. In addition, on the upper lever of the Museum Building is a series of cement paintings.

Smyth learned to cast concrete during his summers doing construction work in the Virgin Islands and Aspen. He compares the process to cooking, a kind of magic as it comes together. “It was, for me, a very contemporary, lasting material.”

Smyth was immersed in the world of classical art from his earliest days, “dragged to every church in Europe” with his father, renowned Renaissance scholar, art conservator and New York University Institute of Fine Arts Director Craig Hugh Smyth.

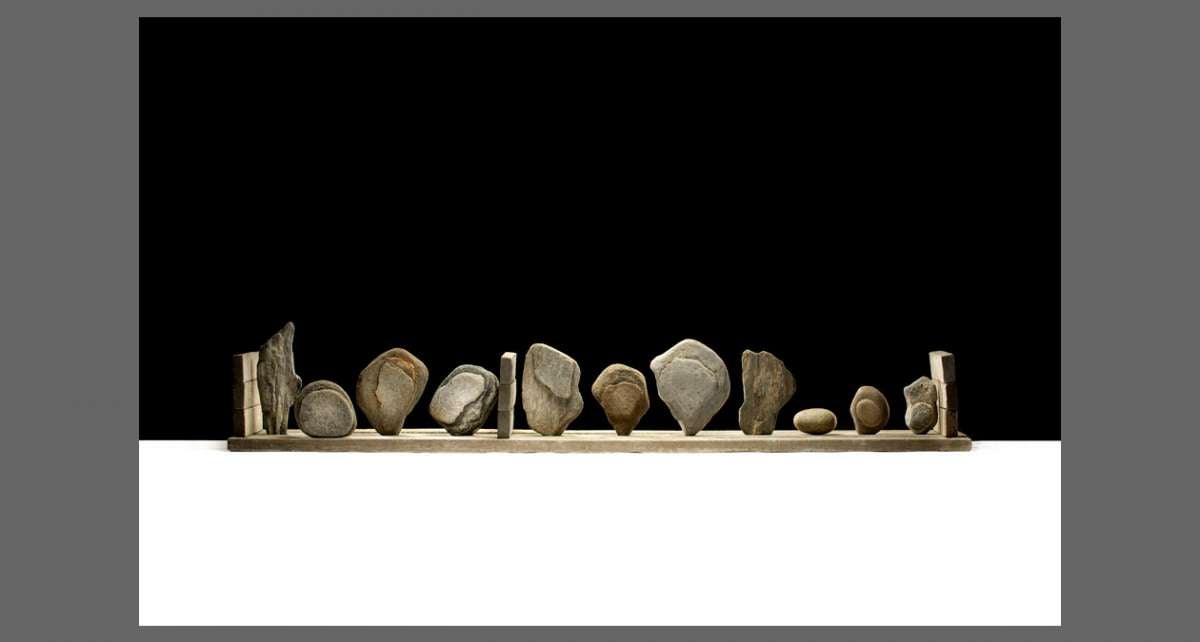

A consummate stone collector, when Smyth moved his studio to Shelter Island, N.Y., in 2002 he found a forgotten cache. This stockpile of stones had grown exponentially. “Like anyone, you go to the beach and pick up a rock… I never thought I had a collection,” he says. “When people visit my house they tell me they collect stones. It’s something that’s innate in all of us.”

Smyth set the stones, from 35 years of collecting, on the studio floor. He stared at them for months and found recurring shapes, themes and affinities. If you were a person one inch tall, walking among them would be like walking through Stonehenge or a Paleolithic site. The stones are so magnificent in their beauty, nothing more need be done to them. And yet.

Some are arrayed on a large white pedestal and convey peace, strength, wisdom. They suggest classical forms of shape and texture. Some are smooth and round, others are pitted and rough, some are monolithic, some balance in unimaginable ways, and others are sensually cradled within each other. The stones have infinite stories to tell.

For Smyth, they have inspired drawings, photographs (six-feet high!), paintings and sculpture. In stone Smyth finds the figure: torsos, wings, portraits, pregnancies. The stones are a form of pre-architecture.

“All these things are natural-stone objects that have been broken off of a mountain, been carried by a glacier millions of years ago, deposited, washed with waves and sand, and shaped,” says Smyth. “And some really relate to history. So it’s Nature, but when you blow it up, it still has that kind of cultural reverence.”

He recounts a dyslexic childhood in the shadow of his super intellectual father—the senior Smyth was one of the “Monuments Men” who recovered art stolen by the Nazis. Smyth says he learned to see from his father. After retiring from NYU the senior Smyth served as director of Harvard’s Center for Italian Renaissance Studies in Florence, and the family lived on and off in Italy. Touring Europe as a child, and accompanying his father on archeological digs, Ned developed a fascination with classical architecture. “I really liked climbing on the ruins at that age, and all the drama and fantasy that went on.”

At Kenyon College, Smyth studied behavioral psychology and probability. “I was a jock, playing semi-pro soccer—my sense of self was as an athlete. Art was my dad’s world.” He’d learned soccer on the streets in Rome and was captain of the team at Kenyon. Then he took a class in color theory from a disciple of Josef Albers, met a new group of friends with whom he stayed up until 1 a.m. and discovered, in his senior year, that he could actually major in art. He graduated with high honors in 1970.

After his experiences with Clark and 112 Green Street, Smyth was awarded a public art installation in 1977, a fountain for the Governmental Services

Administration in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Showing internationally for 10 years, including at MOMA, the Whitney, the Hirshorn, PS1 and the Venice Biennale, Smyth changed his focus to public art. These architectural environments resemble cloisters and arcades with columns, arches and portals and suggest spaces for the expression of reverence. Upper Room (1986), the first art project commissioned for Battery Park City, New York, is made from cast concrete, bluestone and mosaic, and has the look and feel of an ancient roofless temple with columns, a table lined with chessboards, an altar-like structure at its center and a view of the Hudson River.

Visiting the Louvre as a toddler with his parents, Ned ran ahead to the entrance and, they recounted to him later, fell to his knees. Perhaps it was a gesture he learned visiting so many churches. Though never religious, he knew these were places of reverence. He has spent his career re-creating the awe these works inspire.

___________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.