Schoonover Gallery adds another illustrated connection to Delaware at Biggs Museum

In every sense of the phrase, Frank Earle Schoonover was a picture-making man. He was at his best recreating the swagger of seafaring buccaneers in his “Pirates Coming through Charleston.”

It’s one of a batch of illustrations drawn by Schoonover for Ralph D. Paine’s 1922 serialized story of the pirates. Schoonover’s keen eye for color and kinship with the outdoors inspired more than 2,500 illustrations, landscapes, portraits, and stained glass windows in a career that spanned more than six decades and bridged generations.

Born in 1877, Schoonover’s work appeared in most of the popular magazines of the day– Harper’s, Scribner’s, the Saturday Evening Post, and Colliers In addition, his evocative illustrations were commissioned for over 100 books including the classics: Treasure Island, Kidnapped, Blackbeard Buccaneer, and A Princess of Mars. He was inducted into the Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame in 1998.

Back in the mid-1960s Sewell C. Biggs often attended the artist’s Wednesday night salons at his studios on North Rodney Street in Wilmington. Schoonover would enthrall the audience with his discussions on art and they often stayed late to buy works that hung on the walls or stacked high in back rooms.

“The illustrations went for $50 to $100, maybe up to $250. It was a real steal, they might be worth ten times that today,” says the artist’s grandson, John Schoonover, who runs the studio and is a board member of the Schoonover Fund.

The collaboration has come full circle. In January the Biggs Museum of American Art, in partnership with the Schoonover Fund, announced the completion of a fundraising drive to name the new Frank E. Schoonover Gallery of American Illustration at the museum.

Founded in 1993 with the art collection of philanthropist Biggs, the museum has worked extensively with the Schoonover Fund for years on exhibits, educational efforts and the Fund’s comprehensive catalog of Schoonover works. The museum approached the Fund about raising money to rename the gallery. The Biggs Museum probably has more Schoonover works than any other collection in North America, according to Ryan Grover, curator at the museum.

The Fund board agreed to pledge $12,500 for a matching grant challenge that generated roughly $37,500, thus establishing the permanent Frank E. Schoonover Gallery of American Illustration. It is located on the third floor of the recently renovated museum. The gallery walls are painted cadium red, a tribute to “Schoonover Red” that became the signature element in most of his illustrations. Wherever possible, the artist inserted a splash of cadmium red, varnished more heavily than elsewhere to heighten its intensity.

The Schoonover gallery exhibits will change on a regular basis, so revisits are encouraged. Currently, the Biggs houses more than 40 of Schoonover’s works, including “Morgan’s Point was at His Throat,” “Masked Indian Dancer,” 1935 and “Vidette in Pirogue,” 1911.

“Visitors to the Biggs will enjoy significant Schoonover works and memorabilia for years to come,” Schoonover noted. “It helps acknowledge the role illustration played in America dating back to the 1850s and the images from the Civil War. With the grant, the museum is able to formulize their existing Schoonover exhibit and expand on its mission on the recognition of American illustration.”

Fond memories of a former Schoonover student

In the early twentieth century, 1616 North Rodney Street was the epicenter of American illustration. Many of the country’s aspiring young artists had migrated there to study under famed artist and illustrator Howard Pyle. His students were to revolutionize the illustration world by portraying an action scene from an unusual perspective and depicting basic human emotions. Today, Schoonover, N. C. Wyeth, Gayle Hoskins, and Maxfield Parrish and their peers are known as “The Brandywine School.”

Schoonover’s Queen Ann style studio, built by local benefactor Samuel Bancroft, was an expansive structure that housed four large studios, each with separate entrances, large northern light windows, fireplaces, individual bathrooms and storage space. Original drawings, illustrations, and paintings were hung on the walls, canvasses were stacked in foot-high piles with their stretchers removed, and a large birch-bark canoe that Schoonover had shipped down from the Canadian wilds hung high above an easel.

Set on a hill the studio is where Schoonover painted and taught until his death in 1972. Acclaimed Hockessin artist Jim McGlynn recalls growing up a block down the street. He tagged along with his two older sisters to take his first art lesson at age ten in 1954.

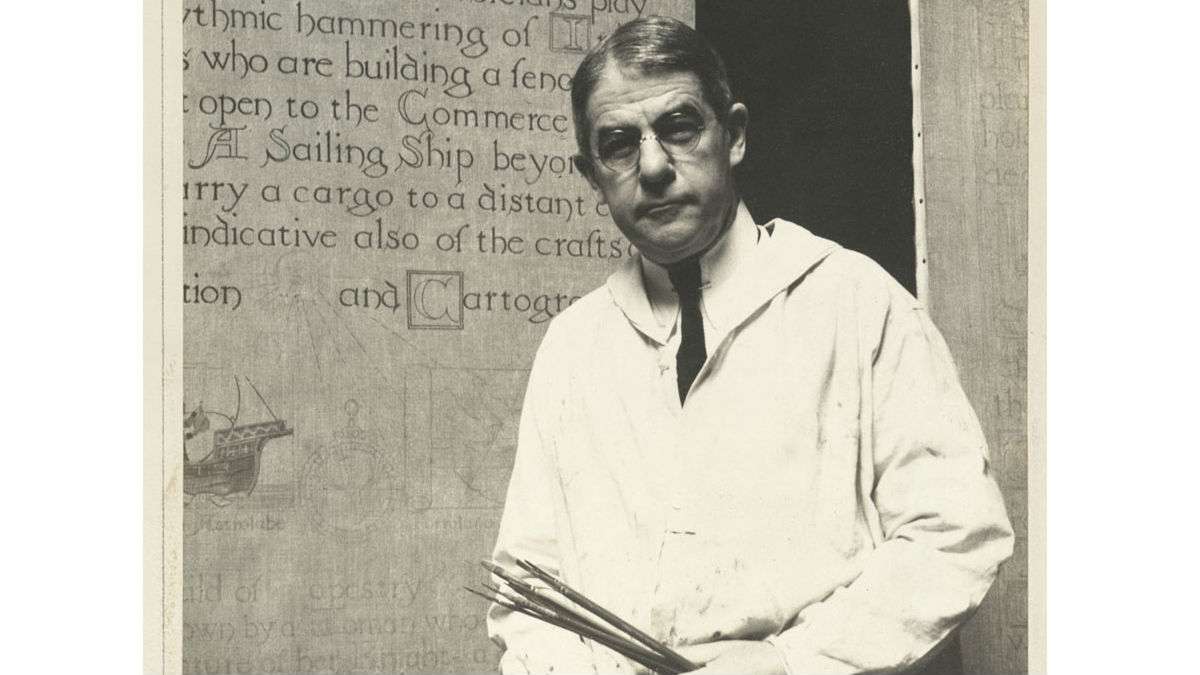

The neighborhood kids saw Mr. Schoonover as the pleasant old man who painted pictures. On Saturdays he gave art lessons for the local children. The artist had an old fashioned appearance, that of a kindly grandfather. He wore wire-rim glasses and dressed in a white shirt and bowtie. He wore a long white smock splotched with a variety of paint colors.

McGlynn remembers that his studio was chock full of incredible objects, almost like a museum to the kids. There were ship models, snowshoes, trade blankets and Indian artifacts, pottery, antique flintlocks, swords, cutlasses, pirate pistols and historical costumes stashed in corners, displayed on chests and bookcases. (They are still there today.) Stretched canvasses, tubes of oil paints and brushes were all neatly arranged. Stacks of finished paintings were in the back room.

“The studio had an incredible smell, a mixture of gum turpentine, oil paints, linseed oil and varnish,” McGlynn remembers. “The large skylight above filtered in a soft, even light across the space. It seemed he always had some large canvas on his sturdy easel that had wheels. Usually, a sheet was draped across during class to hide his painting. We always wondered what was Mr. Schoonover painting.”

The kids painted with pastels on large sheets of paper. They would draw from their imagination, or a still life or a picture from National Geographic magazine.

“He believed children have a natural creativity and Mr. Schoonover could bring it out,” McGlynn observed. “He would walk around to each child and give little critiques to better your work. He would even, ever so slightly, touch up the drawing to teach you how to improve the color or perspective. He would give us pointers on the skies and trees. ‘Always put something alive in your scene, like a bird or people,’ he said.

The kids were honored that he took the time to explain the fresh, still wet painting on his easel.

“’Most artists have a hard time with doing hands, but I don’t,’ he would say. It really was like magic to us to see the colorful palette of paints turn into an almost real hand!”

Schoonover loved the Brandywine Valley’s history and he taught the children that as well. McGlynn remembers asking about the canoe that hung from the ceiling.

“He replied, ‘I was in upper Canada on the Hudson Bay’… Mr. Schoonover was a great man, and artist, but an even greater story teller and friend. He was really something. That’s why all these memories are just like yesterday to me.”

—

Terry Conway writes about arts and culture throughout Delaware and the Brandywine. You can read his work at http://terryconway.net/cms/. You can write him at tconway@terryconway.net.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.