Dollars and scents: Follow your nose through this exhibition at ICA

Norwegian artist Sissel Tolaas has been exploring smells for 25 years. The ICA at Penn is hosting the largest U.S. retrospective of her installation work.

Sissel Tolaas stops to smell a wall imbedded with the recorded and replicated sweat of anxious men at her exhibit ''RE______'' at the Institute of Contemporary Art at Penn. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

With rare exceptions, the art world has been ignoring your nose.

One of the few champions of the olfactory senses as an artistic medium is Sissel Tolaas, a Norwegian-born, Berlin-based artist that has been exploring smells for more than 25 years.

She uses smells in gallery installations that evoke a wide variety of issues, from climate change to cultural memory to the nature of money.

“Smell is everything. Wherever there’s air, there is a smell,” said Tolaas. “It’s why I call myself a professional in-betweener, because life is everywhere. Where there’s smell, there’s life.”

The Institute for Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania is now hosting Tolaas’ first major U.S. exhibition, with the abstract title “RE______.” An earlier version of the show was originally created by the Astrup Fearnley Museum in Oslo, Norway.

“I don’t make fine art,” said the artist. “I make fine air.”

The exhibition begins with the smell of money. Tolaas uses scentography equipment that is able to record the molecular make up of a particular smell, which can then be replicated. She measured the smells of various types of currency, like the Swiss franc, the Deutsche mark, the Euro, and the dollar. A display of 10,000 vials of perfume represents the smell of $390,000, according to the artist’s estimation.

The display of the scent of money is tied to the nearby installation of different kinds of vanilla scents in concrete basins on the floor, with industrial piping suspended overhead. Pure natural vanilla is one of the most expensive ingredients in the world, ounce per ounce on par with silver. Tolaas asks visitors to compare the smell of pure vanilla against a synthetic extract and a flavoring put into processed food.

“You are meant to kneel down and pay attention to this amazing, revealing, and healing capacity of vanilla,” she said, getting down on her knees on the concrete floor and bending her head into her basins. “And then to reflect: What is this all about? What is money? What are we eating? What is currency? What are we exploiting?”

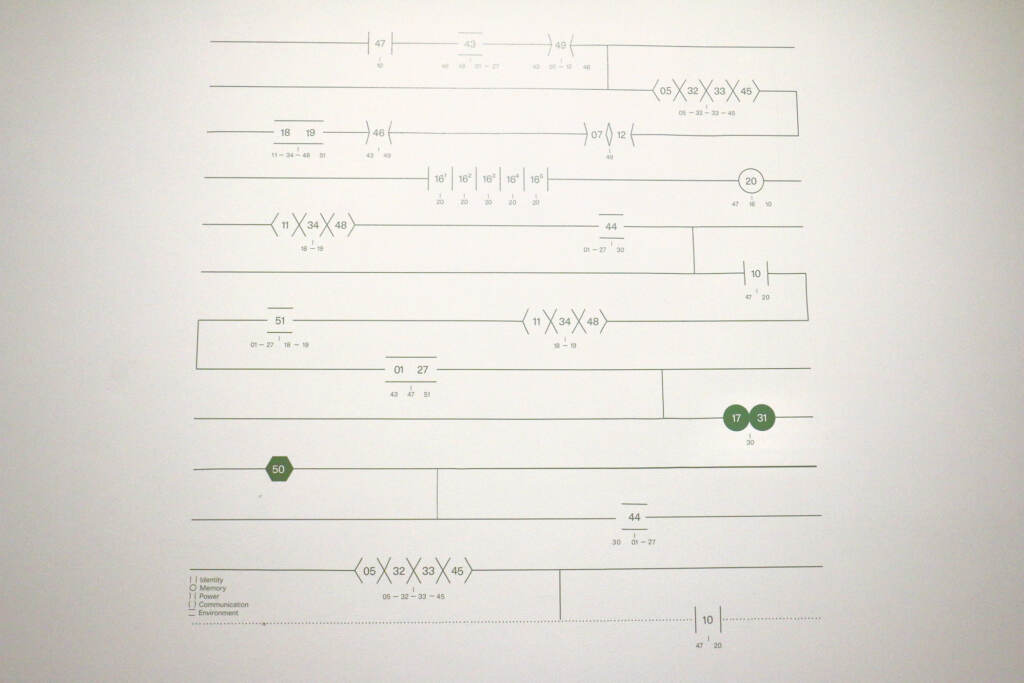

There is very little information in the galleries to guide visitors through the 20 installations Tolaas has designed over the last two decades. There is no wall text. Nowhere in the gallery are the names, materials, dates, and intentions of the various pieces described. The pieces are identified by a cryptic code of Tolaas’s own invention, a graphic of numbers, dashes, and brackets.

Those codes each match that on a paper handout in the final gallery, the “REveal gallery,” which gives some information about the piece it references but even those descriptions are evasive. For example, the text associated with the vanilla installation reads like feverishly jotted lecture notes:

The global is the local is the global

Vanilla is the new currency

Consumption & comfort

Healing & dealing

The familiar, basic, currency, colonialism, race, craft

Tolaas prefers visitors to move through the space led only by their curiosity and intuition, to literally follow their noses. She avoids describing smells, as a wine connoisseur might articulate the flavors of a vintage. Tolaas will never tell you what a particular scent smells like.

“There are no rules on how to explore the exhibition,” she said. “I trust that you will find your way around. I want you to be a child again and use your senses to make sense of my exhibition.”

Visitors are expected to bodily interact with the installations. One of the walls of the gallery is coated in mylar, with several small scent emitters about a foot to two feet above the floor. The emitters are triggered by motion sensors, but the scents emitted are too faint for human noses. Visitors can get on their hands and knees and put their nose directly at the quarter-sized emitter to get a whiff, and realize they are now acting like a dog meeting another dog.

The installation “EI_AI (Emotional and Artificial Intelligence)” is a long concrete bench of various heights laid with five clusters of palm-sized sculptures resembling geometric soap cakes. Visitors are invited to hold them and smell them, to trigger memories and emotions, and share them with others.

Each cluster represents specific places and people, like the Jeju massacre in South Korea, gentrification in Detroit, the city of Wuzhen in eastern China, and the city of Melbourne in Australia, according to notes available at the end of the exhibition. In the gallery space no description, explanation, or instruction is offered.

“The five projects that are here represent the life of people that lived in those various conflicts of the world, as emotional artifacts that you can engage with your own memory and emotions,” she said. “I don’t think we can do anything in this world if we don’t have an emotional reaction. What smell is so intelligently doing is activating one’s emotions.”

The exhibition is tight-lipped about the pieces, avoiding articulating information about smells with the intention that visitors will open their noses to olfactory information. A dark room on the second floor is strewn with what looks like a nerve net of wired smell emitters on the floor. The room is filled with the musky smell of soil, which Tolaas says has healing power.

“Why don’t we just give smell a chance? If there’s a smell, there’s something going on,” she said. “Consider it as very important information for understanding each other and the world we all share and breathe.”

Even the bathroom is part of the exhibition. The soap in the restroom off of the ICA lobby is infused with the smell of Tolaas’s own body. If the smell of her personal odor does not suit you, you can pick up a free vial of money at the exit to dab on your wrists.

“RE_____” will run at the ICA until December 30. Admission is always free.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.