Essay: Rumor hinders healing for Camden fire survivors

-

Brandon Simms breaks down at the memorial to his daughter Laiyannie Williams, killed in a rowhome fire on Morton Street on July 28. Next to him is Laiyannie's aunt, Jamillah Williams. (April Saul/for WHYY)

-

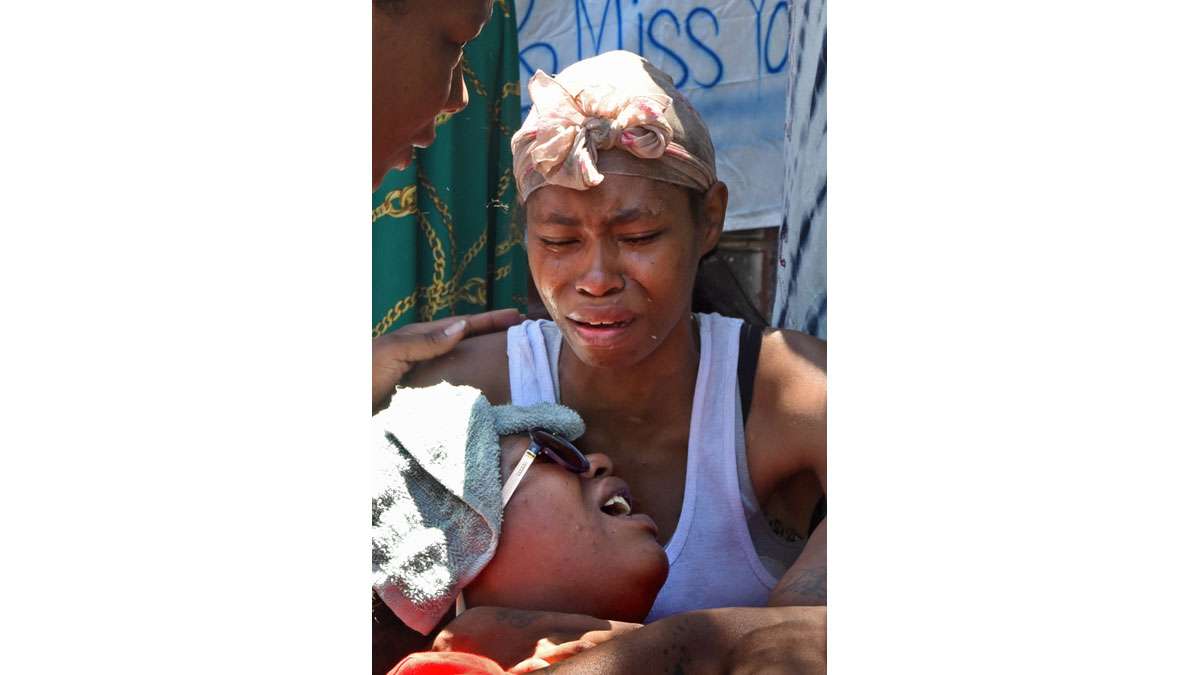

On July 31, 2017, two days after the fire that ravaged their Morton Street home, Jamillah Williams, holds sister Elisha Williams, whose daughter, Laiyannie Williams, was killed in the blaze. (April Saul/for WHYY)

-

On July 31, Elisha Williams, who lost daughter Laiyannie Williams, 4, in the family's house fire on Morton Street, cries; at right is her sister, Jamillah Williams. (April Saul/for WHYY)

-

Outside the ravaged rowhouse on July 31, Elisha Williams, left--whose daughter, Laiyannie Williams, was killed in the blaze--talks to her mother, Victoria Williams, right. (April Saul/for WHYY)

-

On July 31, Zariah Williams, 2; and Aaliyah Roberts, 3; cuddle up with the stuffed animals left in memoriam for Zariah's cousin, Laiyannie (April Saul/for WHYY)

-

On July 31, Zephaniah Williams, 6, plays with bubbles at the sidewalk memorial for her cousin, Laiyannie Williams. Next to her at right is Laiyannie's best friend, Aaliyah Roberts, 3. . (April Saul/for WHYY)

-

Children pass by the sidewalk memorial for Laiyannie (April Saul/for WHYY)

-

A picture of Laiyannie (April Saul/for WHYY

In a place like Camden where the worst is expected, rumors are like preemptive strikes — cushioning potential blows in advance, and giving those who spread them a sense of having some control over life here.

After all, there’s no need to up the ante for sensationalism in a city that in recent years has seen a baby beheaded by his mother and a little boy get his throat slit for defending his sister from a rapist.

Still, the current rumor about the fire that tore through a Morton Street rowhome on Saturday, July 29 is particularly devastating.

It spread almost as fast as the two-alarm blaze that began shortly before midnight, taking the life of 4-year old Laiyannie (“Taco”) Williams, given that nickname for her chaotic, kinetic energy.

Laiyannie’s grandmother, Victoria Williams, heard it before she’d even left the hospital, where she and other family members were treated for smoke inhalation and injuries sustained from leaping two stories to the pavement to escape the fire.

“My stepdaughter came up to me and said someone told her the house was firebombed,” said Williams, 44, who shared the home with her husband, three daughters, six grandchildren and a basement renter. “But I was in the house! I saw the start of the fire.”

The rumor persists even though fire department officials have said there is no evidence to suspect foul play in the tragedy.

A practical nurse, Williams had returned from work and was getting ready for bed when she smelled smoke downstairs and discovered a small fire on a sofa cushion. Williams thought she could put it out herself; but the water pressure was too low in the kitchen and a garden hose she tried to use wasn’t hooked up.

The house filled with smoke. Daughter Tanisha Williams, recovering from a caesarian birth, began tossing five children — her own and those of her sisters — from the second floor to her father, who’d jumped from the roof; a neighbor; and the basement tenant. She then fell into their arms, and passed out; when she woke, she told them Laiyannie had been sleeping on the first floor.

Passersby were videotaping the burning house, yards from where Laiyannie Williams lay dead or dying just inside the front door. “And I’m, yelling “Taco’s on the couch! Taco’s on the couch!” said Williams. “I think they’re starting the rumors so they don’t feel guilty for standing out here and doing nothing.” When Laiyannie’s father, Brandon Simms, saw the fire being livestreamed on Facebook, he ran to the scene.

The morning of the fire, Laiyannie’s mother, Elisha Williams, was taken to jail because she had allegedly missed a court date; family members said she was released the next day by a judge who said she had never been given the date and should not have been imprisoned.

Had his daughter been home, said her father, Desmond Williams, “Laiyannie would have been sleeping in the back room with her. The only time shewas in the front was to wait for her mom.”

A caregiver who fed the homeless in Camden out of her own pocket for a year, Laiyannie’s grandmother Victoria Williams has six children by birth and has fostered two others.

But she could neither put out the fire, nor rush back into the burning home to rescue Laiyannie; when she tried, her husband held her back. In the aftermath, Williams is the sober, capable anchor while other family members numb their grief with drugs or alcohol. “The next person that puts a bottle, a pill or drug to my daughter,” said Williams, “you’re gonna have to see me!

“I know Taco was happier here in four years than some people are in 44 years,” she said. “Now I just need to make sure my family’s all right.”

The vigil

On the night of July 31, a playlist of sorrow blares from a car radio in front of the house, where loved ones keep vigil.

“God, why are you punishing me? I want my baby back!” cries Elisha Williams. At about 9:30 p.m., Simms tries to enter the house where his daughter died. “She’s not in there! She’s not in there!” said Victoria Williams, peeling him gently off the side of the ravaged rowhome.

Williams is heartened by the steady stream of donations the family has received, often from strangers. The rowhouse was not insured.

“There’s no love like hood love,” she said.

The rumors remain a challenge. “One lady that was helping us,” said Williams, “pulled up and asked me, ‘Are you sure your house wasn’t firebombed? I told her, ‘I seen it! It wasn’t even half a sofa cushion.’ One man jumped out of his car, and told Williams, ‘I swear if I find out who did this, I’ll kill him!’ She set him straight, too.

If Williams has a theory about which household member may have accidentally started the blaze, she is keeping it to herself; there has been enough pain.

“Whatever it was,” she said, “it started on that couch and it burned through. Whether it was a kid or a curling iron.”

______________________________________________

April Saul is a Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist who lives in Camden, New Jersey. She writes about the challenges and joys of the residents in Camden on her Facebook page CAMDEN, NJ: A Spirit Invincible. Several times a month she writes essays on Camden for NewsWorks.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.