Rock impresario celebrated at Philly’s American Jewish history museum

One of the giants of rock and roll is the subject of a new exhibition at the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia.

But Bill Graham didn’t own the spotlight. He was a concert promoter who helped make rock a cultural force from backstage.

From his Fillmore club in San Francisco (and later New York), he ushered the careers of Janis Joplin, Santana, Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, the Allman Brothers, and many more.

“Bill Graham and the Rock and Roll Revolution” traces the life of Graham — who died in 1991 — from escaping the Jewish Holocaust as a child to becoming a major cultural force. He helped nurture rock music as a vessel for the ideals of the counterculture: freedom and personal expression.

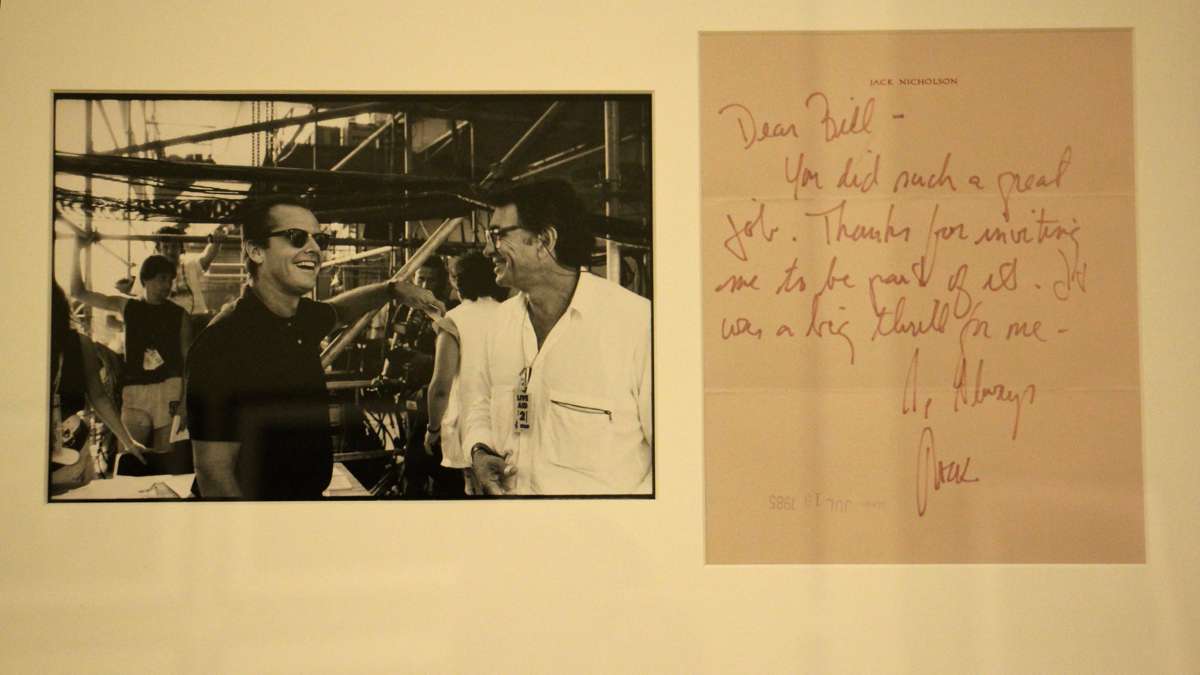

The show is photography-heavy with pictures from Graham’s personal archive (maintained by his sons) and rare pictures of the rock acts he championed, as well as signed guitars from Jerry Garcia, Santana, Eric Clapton, and a shard of the guitar Jimi Hendrix destroyed onstage at Royal Albert Hall in 1969.

“His art were the concerts he put on,” said curator Erin Clancy, who created the show for the Skirball Museum in Los Angeles. “It’s a corny metaphor, but I did think of it that way. The shows, the posters — they were all part of a theater he organized. He was a very theatrical person. He was behind the scenes, but not a wallflower.”

Bill Graham was born Wolfgang Grajonca in 1931, the son of Russian Jews living in Berlin. He father died young and his mother would perish in a Nazi concentration camp. Before she was taken, she entrusted her son to the Red Cross to be sent to an orphanage in France.

Living in a remote chateau with dozens of other malnourished, war-ravaged boys, Graham would get into mischief.

“Sneaking out at night into the orchards surrounded the chateau and stealing apples,” said Clancy. “They were always careful to steal the same number of apples from each farmer so nobody was unduly burdened. They brought these apples back to the boys at the chateau.”

The exhibition opens with a bucket of apples, which Graham used to keep at the Fillmore entrance in San Francisco in the late 1960s. He may or may not have been remembering those early experiences pilfering apples, but he welcomed his guests — ticketholders — with nourishment as they entered his club.

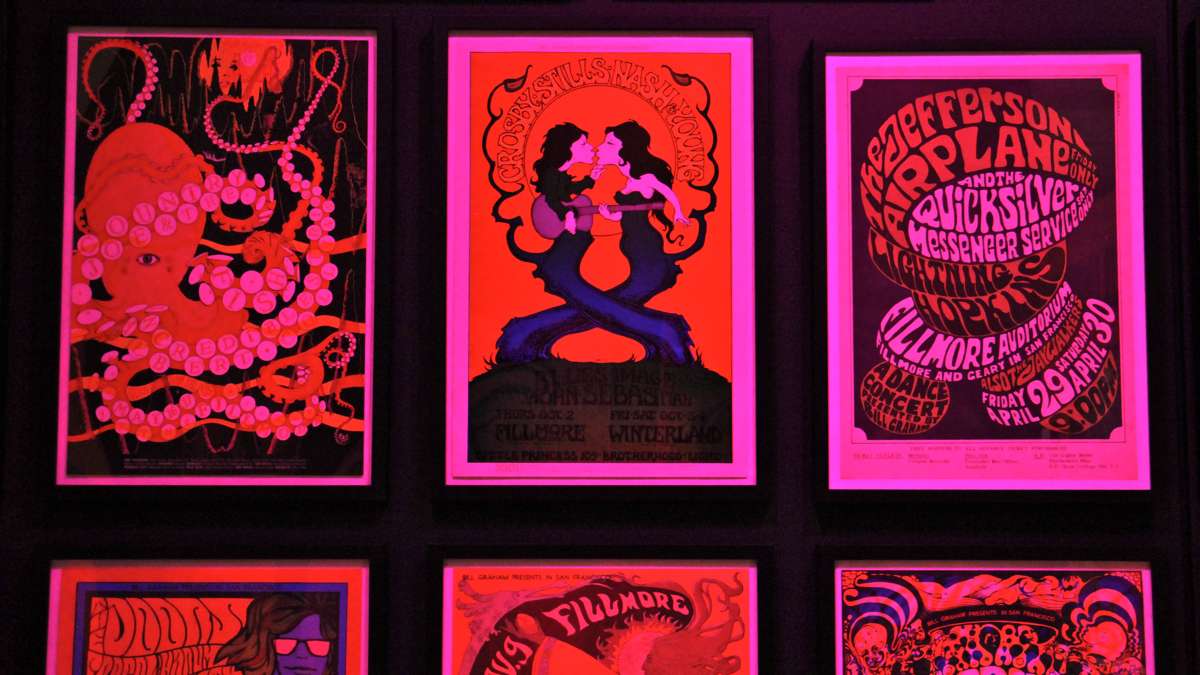

Perhaps his greatest achievement as an impresario was to mix different kinds of musicians on the same bill: psychedelic rock, Latin jazz, and blues musicians might perform the same night. He wanted to educate his audiences.

Graham once said Jefferson Airplane was like ice cream and an older bluesman like Lightnin’ Hopkins was vegetables. “You’ll love him,” he said, “You don’t think so now, but you will.”

He also wanted to maximize his audiences. By drawing from different kinds of music fans, Graham could sell more tickets. The exhibition features two posters for the same concert: one is a swirly, psychedelic layout headlining Jefferson Airplane, and the other is a standard boxing-match layout led by Martha and the Vandellas. Each target audience would surely be surprised to see the other.

Graham was not an observant Jew. He did not go to temple or observe holidays, and as a teenager Americanized himself by randomly choosing a name from the phone book that matched the first three letters of his birth name. Nevertheless, the exhibition shows residual Jewish values expressed in the way he operated his business.

He was one of the first concert promoters to have medical personnel onsite, and he supported free medical clinics in San Francisco and New York. He was a pioneer of the charity concert, staging all-star events for the benefit of the San Francisco School District, Amnesty International, and, with the 1985 Live Aid concert in Philadelphia, famine relief efforts in Ethiopia.

For the exhibition at the National Museum of American Jewish History, curator Joshua Perelman added artifacts related to Live Aid, including the original concert T-shirt and the microphone used by Ozzy Osbourne.

“He also did some other things,” said Perelman. “We remember when Ronald Reagan visited Germany in the 1980s, including a cemetery in Bitburg where Nazis were buried. Bill protested that heavily.”

Graham organized a rally protesting that presidential visit to a Nazi cemetery. A few days later, neo-Nazis firebombed his office, destroying almost everything in it, including an extensive archive of rock and roll memorabilia.

The exhibition features things damaged in that fire, including a melted telephone and a charred menorah. The menorah was a scale model of a two-story menorah he helped finance for installation every Hanukkah in San Francisco’s Union Square.

The exhibition continues until January.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.