Roadside Americana on Lancaster Avenue

PennDesign student and community contributor Angelina Jones uncovered an interesting roadside relic in Mill Creek, which helps illuminate the history of both the Lincoln Highway and Americans falling hard for their cars. Here’s her appreciation:

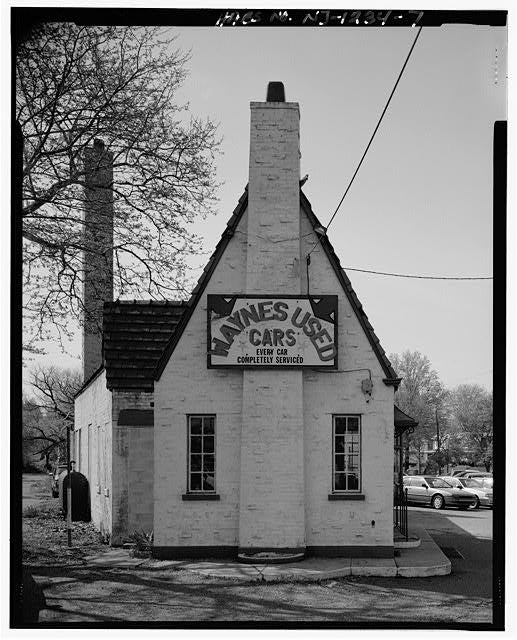

On a triangular lot bordered by Lancaster, Westminster, and Belmont avenues in Mill Creek, sits an empty 90-year-old service station. At first blush, its blue pitched roof hints at its once-storybook-worthy appearance. It’s hard to tell that this humble building is actually an important mile marker in the history of American automobile travel and in the life of Lancaster Avenue.

Pure Oil built this “house type” service station in 1925, taking design inspiration from an English cottage, adding the more contemporary touch of a gabled roof clad in vibrant terracotta tiles. This is the look that would define the company’s architectural identity during the 1920s and 1930s. Companies like Pure were shaping roadside America as ever more Americans were falling into their long love affair with car travel.

By the early 20th century Lancaster Avenue and Lancaster Turnpike had already long been used for distance travel – first by horse and carriage, later trolley and car. That history made Lancaster Avenue an obvious choice to be incorporated into the Lincoln Highway, the first interstate roadway specifically intended for automobiles, when it was built between 1914 and 1925.

This Pure Oil Station was built along the Lincoln Highway route, part of a growing roadside infrastructure to promote automobile travel between New York and San Francisco. The station on Lancaster Avenue served travelers between Philadelphia and Lancaster. Among Pure Oil’s locations along the Lincoln Highway, at least three others remain today in Pennsylvania and Illinois. Pure Oil was headquartered first in Ohio, moving in 1926 to Chicago. In 1965 Union Oil of California purchased the company.

Pure Oil was one of the first gasoline stations to locate in what was then a suburban landscape. Before the 1920s, gasoline stations were considered unsightly fire hazards and were typically not located in residential areas. The Pure Oil station built on Lancaster Avenue in 1925 is an early example of how this now ubiquitous architectural type was made attractive to suburbanites. It was intended to resemble a scaled-down single family home complete with lawn and flower boxes.

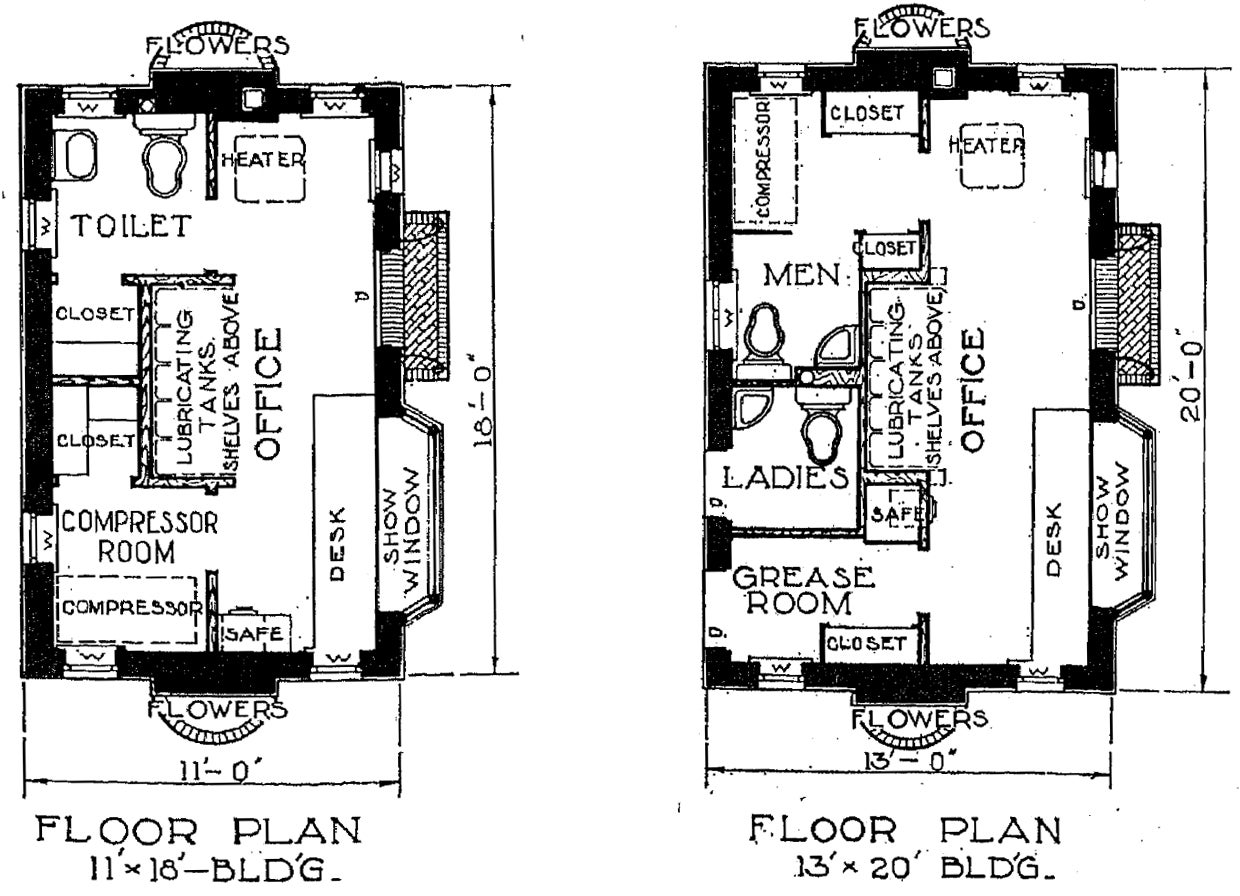

The person behind this design, Carl August Petersen, was the Chief Engineer of Marketing Construction for Pure Oil in the 1920s. The suburban identity projected by Pure Oil stations was patented in 1928 and carefully dictated to franchise owners. In fact, Petersen stipulated what features had to be removed when a station was withdrawn from the Pure Oil chain. This means that the station on Lancaster would have ceased to be called Pure Oil in 1965 when the company was sold, but there is evidence that it operated as a petroleum gasoline station until 1984, when four gasoline storage tanks were removed from the site.

The Pure Oil Service Station at 4431-4435 Lancaster Avenue, currently owned by Kevin Bunch according to city records, is vacant but is perfectly situated to serve a new commercial use. One former Pure Oil station in Harrisburg has been converted into a coffee shop and one in Geneva, Illinois has found a second life as a plant nursery. This particular station was a grocery store and kerosene fuel station until the late 1990s.

Vernacular gas stations such as these are vanishing rapidly with the emergence of large national chains such as Wal-Mart and Costco selling gasoline. An adaptive re-use of this building in Mill Creek, where the historic landscape is so often ignored, would preserve an early example of this disappearing architectural type and an original Lincoln Highway landmark.

Typical Cottage-style Pure Oil Stations:

This article appears as part of an ongoing collaboration with PennDesign’s Graduate Program in Historic Preservation, highlighting student research and documentation of Philadelphia history.

The author wishes to thank Professors Aaron Wunsch and Francesca Russello Ammon at PennDesign and William Whitaker at University of Pennsylvania’s Architectural Archives for assistance with this article.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.