Rizzo, Rocky and lots of Ben Franklin: Is 2020 the year to rethink Philly’s monuments?

As Philadelphia grows and changes, so must the city’s approach to commemorating history, writes Monument Lab’s Paul Farber.

Mel Chin, Two Me, City Hall, Monument Lab, 2017. (Steve Weinik/Mural Arts Philadelphia)

This is an excerpt from “How to Build a Monument” by Paul Farber from Monument Lab: Creative Speculations for Philadelphia edited by Paul M. Farber and Ken Lum.

Imagine that every monument installed across the city of Philadelphia, just briefly, comes to life. Each statue, whether a mythological or historical figure, rendered in marble or bronze, positioned in a heroic stance or seated in repose, scattered across neighborhoods and municipal perches, loosens from its foundations. In turn, the busts of prominent Philadelphians blink and cast oblique glances as if to exhale. At City Hall, three distinct Benjamin Franklin sculptures on the north side of Broad Street look quizzically at one another, as a singular statue of the African American freedom fighter Octavius Catto, on the other side of the building, completes a long step toward the site of his old South Philadelphia home. Beyond the statuary, voices ring out for recognition, as the spirits of those namesakes at parks, schools, boulevards, and recreation centers clamor. A similar chorus emanates from historic markers placed outside famous Philadelphians’ homes or sites of protest. The city is filled with noise and dust, generations of entangled mother tongues and musical notes. The living are compelled to pause, a grand reversal.

In this scenario, the dream revelation beckons further speculation. Would the underrecognized civic leaders and ancestral ghosts who have never achieved monumental recognition raise their voices as well? Would their improvised shrines, mossy headstones, and memorial murals cast skewed shadows? From such a vantage, would we, as witnesses, fully register the outcome of the processes that continue to shape the city’s monumental landscape: that we elevate a disproportionately wealthier, whiter, more militaristic, and overwhelmingly male version of the past above others, in our monuments and our social systems? Are we reminded once again that history is not restricted to our past but is a force in the present?

We live in a city defined by the premise that history was, and is, produced here. Our grand narratives of this place—as Lenape tribal lands, green country town, birthplace of democracy, workshop of the world—are braided together and offered as enduring points of pride. By now, the stories are as much topos as ethos, because it would be hard to imagine this city without the encounter of William Penn and the Lenape chief Tamanend, the outline of the Liberty Bell, the outstretched arms of the Rocky statue, and other iconic symbols as shorthand for civic identity. The city presents itself as a cradle of liberty, and these stories are often leveraged to nourish greater forms of belonging and justice, locally and else-where. While these identifications may sustain, in part, such declarations are nonetheless also haunted by what remains largely unregistered in official modes of public history. Displacement, economic inequity, racial and ethnic violence, and gender and queer exclusion are among several deeply underrepresented pillars of city order. As sites of spectacle and triumph, civic monuments participate in this simultaneous presentation and occlusion of what we have remembered, and, at a municipal level, what we have willfully forgotten. Perhaps this is why Essex Hemphill, who lived his final years in Philadelphia, wrote these words about the crisis of compassion and intervention during the AIDS epidemic:

It’s too soon

to make monuments

for all we are losing,

for the lack of truth

as to why we are dying, who wants us dead,

what purpose does it serve?

Here and elsewhere, ambivalence permeates the cultures of monumentality. Who should be honored? Who decides what to remember, and what form should that remembrance take? Who should build the monument? When, if ever, is the right time to commemorate? No matter how grand the scale, history cannot fit into a statue, a plaque, or a marker. Our practice of celebrating elite individuals or transcendent agents of social change often obscures stories of struggle, solidarity, and collective action. Gary Nash highlights “a certain silencing” enacted through much of our city’s history by the powerful stewards of artifacts, museums, and institutions who have shaped our understanding of the past while uplifting their own self-interests. For generations, artists, activists, and students have led new directions in the field, adding platforms for exchange, catharsis, interaction, and accountability through the monumental form. They remind us of sprawling narratives and missing monuments that present a different map of our civic landscape. We, too, as engaged residents and practitioners, are invited to attempt to disentangle myths and reassess our monumental inheritances.

Monuments operate as statements of power and presence in public space. No longer bound by static representations, we have lived through a sea change around monuments, in which creative communities respond to triumph and loss. Scholars such as David Blight, Svetlana Boym, Erika Doss, Toni Morrison, Lisa Saltzman, Kirk Savage, Marita Sturken, Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Dell Upton, and James Young have long argued that monuments no longer signify the universal, idealized, and permanent. Traditionalists may balk at the idea of a monument as anything other than the elevated icon, a single figure of history embodied as a spectacle. But when we consider the most epiphanic, gripping sites of memory—Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial and Bryan Stevenson’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice, among them—the physical form of the monument indexes the bygone individual life amid the broader, turbulent currents of history, as memory confronts us in the present. Despite these advances, we have not fully revised the thinking about what a monument is or whom it addresses and for whom it carries value.

And so, the challenge remains: for every new site of reinterpretation and reinvention, there are hundreds that reflect an obdurate status quo. We face a long task of remediation, a process of critical engagement, inspired by environmental practitioners, to diagnose and take steps to address sites with toxic narratives and practices of exclusion as a way to respond to recent and long-standing nationwide conversations about what to do with the incomplete monumental land-scape we have inherited.

We should know by now that history is not written simply by the victors; it is inscribed by those who have the time, money, and power to build monuments. But we also have learned, time and again, that those who lack time, money, or power can stand, gather, or resist next to a monument to amplify their presence, make their voices heard, and confront the systems that wrought the monuments.

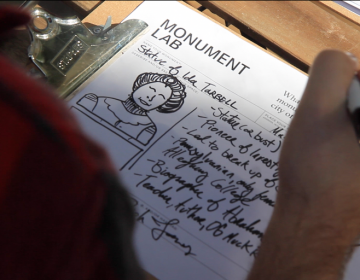

Monument Lab—the name of the ongoing public art and history studio as well as of the exhibition documented in this catalogue — was born out of Philadelphia’s complex legacies and layers. As a curatorial team, we conceived of the project at a moment in which cities across the United States are pondering their cultures of commemoration, and one in which our own city is experiencing a wave of urban renewal paced by historical dilemmas.

Philadelphia’s recent recognition as the first U.S. World Heritage City was contemporaneous with a building boom in which developers routinely bulldoze historic row homes, churches, and factories for new commercial projects. The business of higher education spurs millennial civic engagement, while the legacy of neighborhood school closures and budget cuts looms over a generation of underresourced youth. And, in this moment of national reckoning with monuments, especially those that reflect racist and unjust legacies, this city’s collection of more than fifteen hundred monuments includes only one figure of color on city land and two historical women on public land. Even if we count the handful of statues at the corporate-run stadiums and on private property or the unnamed figures in groups, it is evident we are ready for more conversations about the history and trajectory of the city.

Material drawn from “How to Build a Monument” by Paul Farber from Monument Lab: Creative Speculations for Philadelphia edited by Paul M. Farber and Ken Lum. Used by permission of Temple University Press. ⓒ 2020 by Paul M. Farber and Ken Lum. All Rights Reserved.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.