Rider University to show exhibit of the late John Sears

This is part of a series from Ilene Dube of The Artful Blogger.

In 1985, John Sears was riding his bicycle to George School in Newtown, Pa., where he worked as an art teacher for 17 years. Cited by the Rhode Island Institute for Design as one of the nation’s outstanding art educators, Sears had enjoyed cycling since his boyhood in South Bend, Ind. He and Anne, his wife of three years – it was a second marriage for both of them – lived in a townhouse on the George School campus.

He had to ride through the woods and past St. Mary’s Hospital, and that’s where he was hit by the car that nearly killed him. “I was lucky to be so close to a hospital,” he said several years ago. The accident left Sears with a traumatic brain injury.

Rider University Art Gallery will exhibit Contrast, a show of Sears’ drawings and paintings before and after the accident. The exhibit runs Sept 19 – Oct 13, with an opening reception Sept. 19, 5 to 7 p.m. Sears passed away in 2009 as a result of complications from the accident.

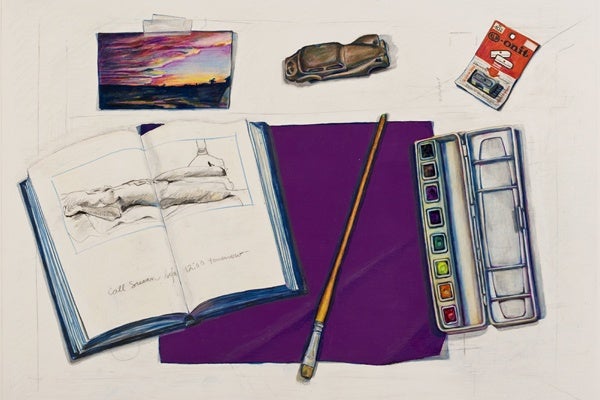

One highlight of the exhibit will be works from his Sketchbook Series, a collection of still-life drawings and paintings centered on the sketchbook that was always at his side and significant objects in his life.

“The works selected for this exhibit both illustrate and symbolize John’s core belief in art and in life: Contast is the key,” says his widow, Anne Sears. “He emphasized to his students the importance of contrast in art. He also recognized that life is inevitably filled with contrasting experiences, happy and sad, good and bad. He even named his boat Contrast.”

In conjunction with the exhibit the Rider University Art Gallery will host a panel discussion focusing on creativity in the face of challenge September 26, 7 p.m. Gallery Director Harry I. Naar, artist Cynthia Groya, Rider University Psychology Professor John Suler and Anne Sears will discuss what drives people to create despite physical, emotional or economic challenges and ways to support the creative spirit that lies in all people.

Shortly after the accident, doctors handed Sears a manila envelope and asked him to draw on the back of it. There were meandering pencil scrawls and in the center, letters spelled out “HELP.” After intensive care, he spent six months in inpatient rehabilitation. After he was released he spent two years in outpatient rehab.

Over the following 24 years he struggled to continue his work as an artist, learning to compensate for the challenges his disability presented.

“Making art has been a central part of my life since I was a child,” he is quoted in exhibition materials. “After my accident, when the doctors told me that I might not be able to make art again, I couldn’t imagine living without being able to create. Using as much will and determination as I could muster, I kept on trying, so that I could again work in my studio.”

His disabilities included partial paralysis – he walked with a limp – speech disorders, depression, memory problems, and double vision. He tired easily.

For a time after the accident, he was too depressed to get back to his artwork. He would sit in his studio for hours and cry. Sears was so depressed he walked to the SEPTA bridge over the canal and thought about jumping in.

After resisting medication, Sears finally began a course of antidepressants, which enabled him to have a show at George School. It was two years after the accident, and the artwork sold out.

That first work, all in black and white, was dark and gloomy.Before the accident, Sears appears to have been in love with the sky, having created a series of skyscapes. He had a friend from Princeton with a ketch, and the pair would go to Bermuda and sail back to New Jersey. After returning home, Sears created a series of pastel images that capture visions of life at sea: a corner of the ketch and the rigging, a sunrise hidden behind the clouds reflected on the Atlantic Ocean, a hole in the sail as it blows in the wind.

Sears was also inspired by the travels he took with Anne:a Tuscan farmhouse, Moorish ornate ironwork on the Casa de Pilatos in Seville.

After the accident, he spent a good amount of time in the car, being driven by his wife. He filled sketchbooks with intricate pen-and-ink drawings of her head looking out through the windshield, against the steering wheel, with detailed reflections in the side mirror and the rear-view mirror.

His early work was more exacting and precise, Anne points out, and some people actually prefer his later looser style. “It has more freedom,” she says.

The sketchbooks are like diaries: There are scenes from a concert at Bristol Chapel, Westminster Choir College; abstracted links from a bicycle chain.

Bicycles are a recurring theme in his work. In more recent years he rode a recumbent bike on the towpath into downtown Yardley, where he might get a haircut or fill his basket with purchases. Attached to the helmet was a rearview mirror, which inspired more sketches.

While it may seem like a miraculous recovery, there were still dark days. “John had tremendous spirit and motivation even on days he was pulled down by depression,” says Anne. “He fought his way out of the darkest corners. He was like a toy clown with a weight that always sprung back up no matter how many times it’s knocked down.”

_____________________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.