Review of Philly schools could mean closures, boundary changes

The announcement could unnerve homeowners in gentrifying neighborhoods or neighborhoods with low-enrollment schools.

Andrew Jackson Elementary School has become one of the most popular schools in South Philadelphia. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Update: 3:15 p.m.

In a move that could have a major impact on city parents and homeowners, the School District of Philadelphia announced Tuesday that it will reexamine its network of neighborhood schools to plan for predicted enrollment changes.

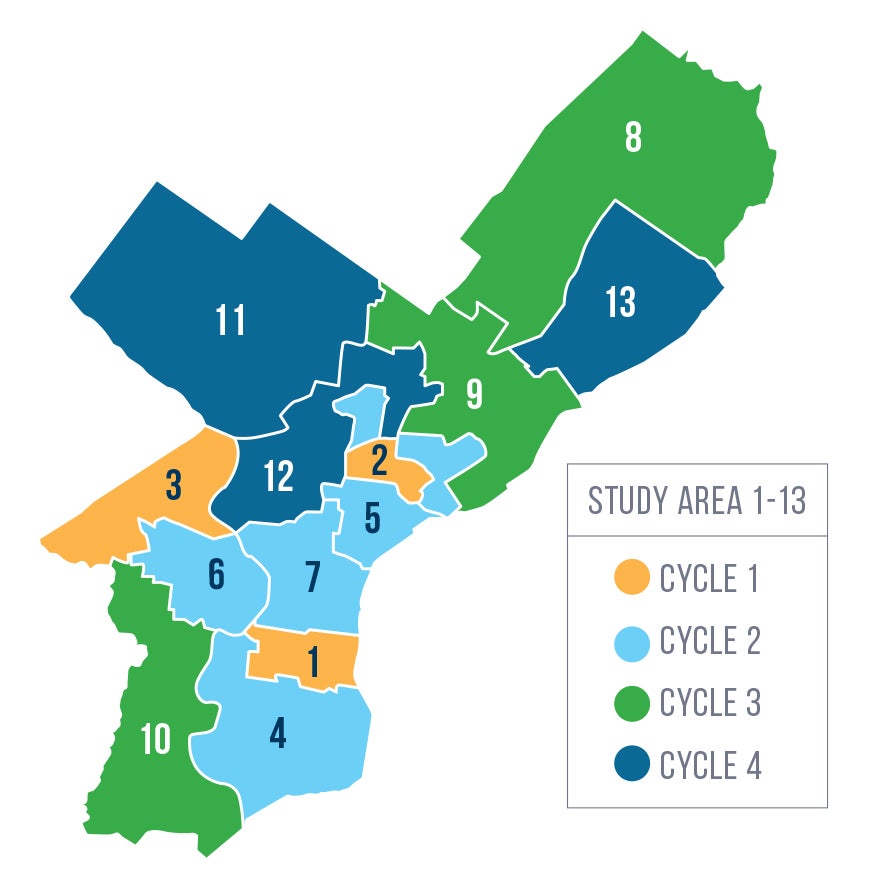

This four-year process, dubbed the “Comprehensive School Planning Review,” will touch every corner of the city and could lead to school boundary changes, school closings, school openings, capital improvements, and shifts in grade-configuration.

“One of the things we’re trying to do here is emphasize a forward-thinking approach,” said Superintendent William Hite.

The first three areas to receive focused attention are parts of South Philadelphia, Kensington, and West Philadelphia.

The process, a first in recent memory, will include extensive public input in each of the 13 “study areas.” Each section will have a planning committee that includes parents, principals, district officials and the local City Councilperson.

Hite, Chief Operating Officer Danielle Floyd and Chief of Schools Shawn Bird emphasized that the process goes beyond facilities and school boundaries. They plan to work with the city planning department to leverage other public resources while focusing the district’s capital improvement dollars on changes they hope will ultimately improve learning.

“It’s not just about facilities improvements, but how do we design schools to meet the educational needs of children in those communities,” Hite said.

District officials believe this process will help them better manage overcrowding and underuse in city schools. But this announcement could also unnerve homeowners in gentrifying neighborhoods or neighborhoods with low-enrollment schools.

Over its history, the district has more often reacted to enrollment shifts rather than anticipating them.

Hite’s tenure began with a school-closure process that resulted in the shutdown of 23 schools based on recommendations from the Boston Consulting Group. To much public outcry, BCG originally suggested that 40 to 50 schools be closed immediately and another 15 to 20 in subsequent years as a response to a precipitous decline in district enrollment largely due to the rise of the charter sector.

In the past, the district’s planning for demographic changes — such as those that roiled the city during the height of white flight starting in the 1950s and 1960s — was opaque. It remains a mystery how district officials decided historically where to build schools, how to set catchment boundaries, and when to shut a school down — all moves that both responded to and influenced the rapid racial transformations of many Philadelphia neighborhoods during the last half of the 20th century.

Even a 40-year lawsuit by the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission accusing the district of discrimination and seeking active desegregation measures failed to fully explicate how such decisions were made.

The current district leadership thinks its new process will be more predictable, transparent, and thoughtful than past iterations. They hope it will allow them to make proactive decisions, ensuring that every neighborhood in the city receives some focused attention once every four years.

But this announcement also introduces some unpredictability into the city’s development landscape.

Catchment boundaries drive home values in many areas of the city, and prices have soared recently in some gentrifying areas that have well-regarded public schools. Moving boundaries even a block could create perceived winners and losers.

Some parents in these multiplying pockets of the city have begged the district to take a more proactive approach to overcrowding issues. And district officials tried to downplay the prospect of redrawing attendance areas, saying it was just one of many options on the table.

South Philadelphia — where housing prices and school enrollment boomed over the last decade — is one of the areas under review in this first cycle.

“We’ve been asking them to do something systematic for several years,” said Dare Henry-Moss, an education advocate who lives in South Philly. “Because any choices that are made about individual schools affect the schools around them.”

Henry-Moss, who plans to send her child to Andrew Jackson Elementary in the fall, thinks some neighbors will be “apprehensive” about the planning review, but she’s cautiously optimistic the district will take a “more thoughtful approach” than it did in the 2013 closure process.

“Study Area 1” includes development-heavy neighborhoods such as Point Breeze, Graduate Hospital, Bella Vista, Queen Village, and East Passyunk.

“Study Area 2” covers Fairhill and the northern fringes of Kensington, where schools have varying grade spans, meaning that many students must switch schools one or more times before they get to ninth grade.

“Study Area 3” focuses on neighborhoods in far west Philadelphia, including Overbrook and Wynnefield, where a replacement school for Cassidy Elementary is planned.

(For a complete list of schools in Cycle 1 see below.)

None of the 23 school zones in this first cycle of review will see any changes until September 2021 at the earliest.

To kick off the process, the district says it will hire an outside firm to help administrators predict the demographic changes Philadelphia will undergo in the next decade. Officials expect this review to cost $1.4 million over the next four years.

The district will also form study area planning committees (SAPCs) for each of the three regions under examination in this first cycle of review.

These SAPCs will feature two parents from each school in a given region, principals from each school under examination, assistant superintendents, district staff, elected officials, and city employees. District leaders mentioned that the city’s planning department would be looped into each of these SAPC groups.

The SAPCs will do a year of “analysis and community outreach,” according to the district. By May 2020, each SAPC will presented recommendations to the Superintendent and Board of Education. After a public comment period, the Board of Education will take a final vote on each plan.

For the past year the District has been planning a new school in the overcrowded Mayfair section of Northeast Philadelphia to replace Austin Meehan Middle School, using a similar community process. Among the decisions that came out of that outreach is to make the new school a K-8 school rather than a middle school, Floyd said.

The first group of catchments under review are:

Study Area 1

Arthur

Childs

Jackson

Kirkbride

McDaniel

Meredith

Nebinger

Southwark

Stanton, EM

Vare-Washington

Study Area 2

Cramp

deBurgos

Elkin

Munoz Marin

Potter-Thomas

Sheppard

Willard

Study Area 3

Cassidy

Gompers

Lamberton

Mastery (Mann)

Overbrook

Universal (Bluford)

The story of Philadelphia’s public school system follows about the same trajectory as school systems in other post-industrial American cities.

Philadelphia’s enrollment plummeted in the back half of the 20th century as the city bled population and its suburbs boomed. A school system built for a population of 2 million had to adapt as the city lost about 500,000 people.

Since 2000, the city’s population has stabilized and so has the number of students attending public schools. But the emergence of the charter school sector has reshaped the distribution of those students.

In 2001, there were 201,000 students in district-run schools. By 2016, that number had dropped to 134,000, with most of the remainder attending charter schools.

This combination of demographic changes and charter growth left the district with scads of half-empty buildings. And despite the closures in the early part of the decade, there are still many buildings with enrollment at less than 50 percent of capacity.

Before utilization rates worsen, district officials want to implement this planning review process as a way to decide how they can best use their remaining infrastructure.

They also want to ensure overcrowding concerns don’t blunt the momentum of public schools in fast-growing parts of the city.

Even though the district as a whole hasn’t made sustained enrollment gains, numbers are up in some neighborhoods with large immigrant populations and there’s clear enthusiasm for public education in some gentrifying areas.

“This is something we’re seeing not just in Philadelphia, but in cities around the country,” said Maia Cucchiara, a Temple professor who has written about the interplay between gentrification and public schools.

Cucchiara said the story of schools in South Philadelphia has played out in parts of Brooklyn and Chicago. And it’s raised a larger question: how do districts respond to the demands of this relatively affluent parent group without worsening inequity?

Cucchiara would like the district to prioritize integrating schools along racial and socioeconomic lines during its process. District leaders wouldn’t commit to this idea, saying they’ll listen to feedback from community members.

The district wants this type of exchange to become routine, and the hope is that these four-year cycles of review will continue into perpetuity.

“This should be something people come to expect as just a part of how we plan,” said Hite.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.