Reuse of the City Branch for transit or trails unlikely, but proposed development isn’t to blame

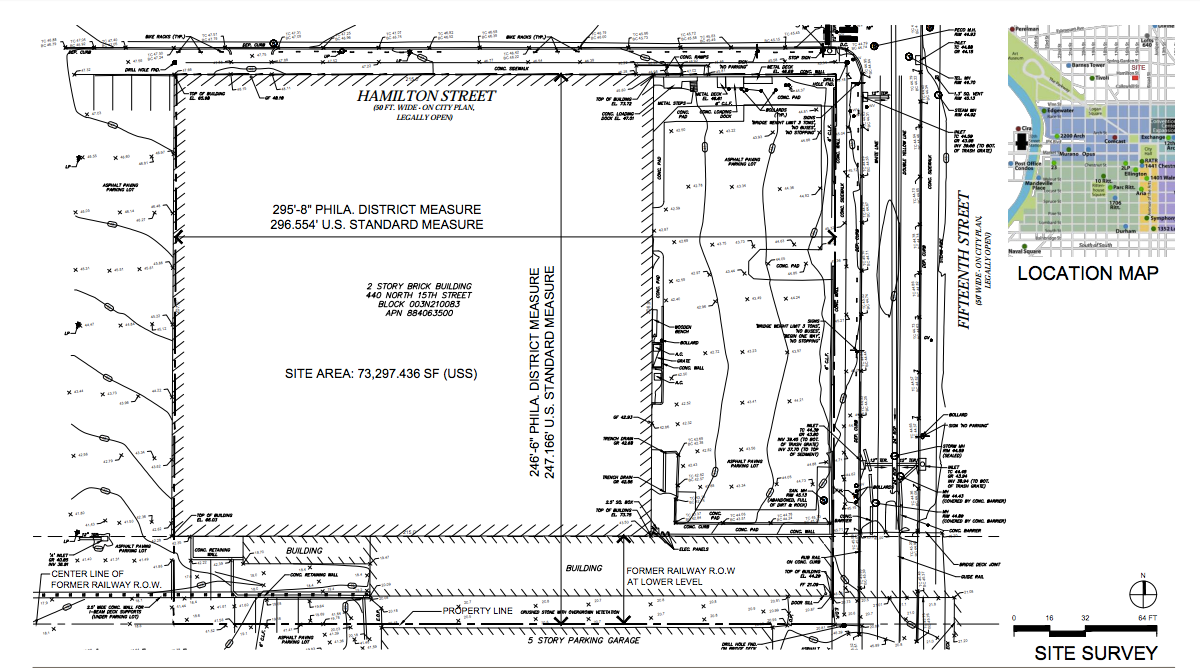

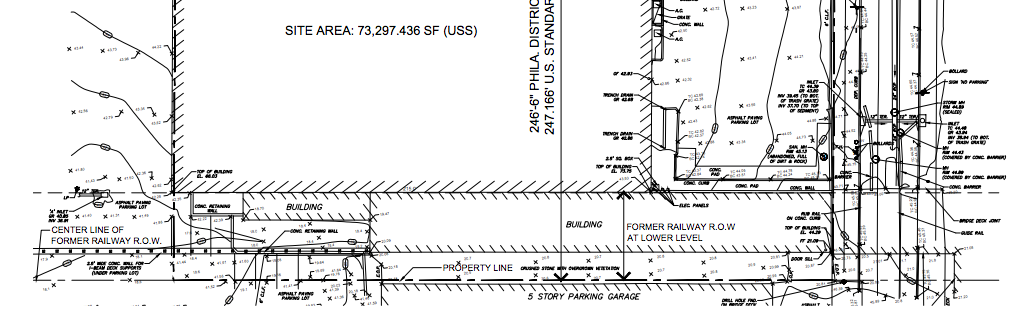

When plans for a new mixed-use development at 15th and Hamilton streets in Spring Garden were posted online in advance of this month’s Civic Design Review, the project caused a stir among some of Philadelphia’s hyper-vigilant urbanists. The new building appeared to block the below-grade rail right of way that originally connected to the nearby Reading Viaduct.

The City Branch, as this right of way is known, runs from 30th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue down to 13th and Noble streets, in tunnels and open-air cuts. Building into its right of way would undermine some of the long-term ideas for repurposing the City Branch for transit, trails, or a combo of both—from some of the proposal’s diagrams, the development seemed to block up the tunnel altogether.

Not so, says Dave Yeager, principal at Radnor Property Group LLC, which is developing 440 N. 15th Street along with the property owner, the Community College of Philadelphia (CCP).

“Some people look at the plan and go, ‘Oh my God, they’re building into the right of way,” says Yeager. “But no, it’s there already.”

“It” is the basement of the warehouse that sits on the property today, which Radnor wants to repurpose into an underground parking garage. The basement already juts into the City Branch, narrowing it significantly. But it doesn’t block it completely—it just appears to do so from the plans, which don’t show the full width of the right of way.

Yeager said he’s a big supporter of the nearby Rail Park currently under construction, which is turning a different, above-ground section of the same former Reading Railroad viaduct into a park. In 2013, the Friends of the Rail Park—the nonprofit largely responsible for the upcoming park’s existence—released plans that envisioned a City Branch extension that would turn the Rail Park it into a 2 mile long linear park with above-and-below ground elements.

The Radnor Property development wouldn’t prevent that plan, but it does make it less likely by ensuring that the City Branch will remain about 80 percent narrower for that block long stretch.

“If that were the worst problem the park [extension] faced, I’d say ‘woo hoo!’” said Aaron Goldblatt, a director on the Friends of the Rail Park board. Goldblatt would love it if Radnor and CCP removed the existing structure in and decking over the right of way to widen and improve the City Branch’s potential as a park, but he’s also realistic. Goldblatt, who lives nearby and serves on the Logan Square Neighborhood Association, supports the project, calling it good for CCP and the community. Besides, the Rail Park has another, “more realistic priority” for expansion, said Goldblatt: the elevated viaduct’s main branch, which Reading International still owns.

Goldblatt is heartened by what he calls Radnor’s “passive” commitment to the Rail Park extension. If the city wanted to open the tunnel as part of a larger linear park or trail, Radnor said they’d accommodate that by providing access to it by opening up a stairwell at 15th Street to the parking lot. “To the extent there is a real effort on the city’s part, we’d certainly cooperate,” said Yeager.

For now, though, there isn’t a real effort by the city, or anyone else with a real say in this. SEPTA, which owns all of the City Branch except for the section between 16th and Broad Street where this project is, has no plans for it, said SEPTA Director of Strategic Planning Byron Comati.

“I can’t say with much conviction that there is a meaningful use of the asset,” said Comati. “It’s just not hitting us.”

“It’s an infrastructure nightmare,” adds Comati. “At some point, we’ll need to spend some dollars to maintain it.” SEPTA would rather put that money towards maintaining and expanding its active transit lines.

SEPTA originally bought most of the City Branch from Conrail in the early 90’s, when it was looking to create a Regional Rail line linking Center City Philadelphia with Reading. (Conrail sold off the stretch between 16th and Broad before SEPTA could buy it.) When that plan fell apart, the transit authority wound up with a 1.75-mile-long stretch of decaying infrastructure without any real idea of how to use it.

“It’s a dangling participle, it’s just stranded,” said Comati. “And that’s the shame of it. But I can’t change the history of it.”

As development starts to boom just north of the Rodin and Barnes museums, it’s increasingly likely that SEPTA will sell off the land in bits and pieces to developers. Some properties already lease parts of the City Branch for parking.

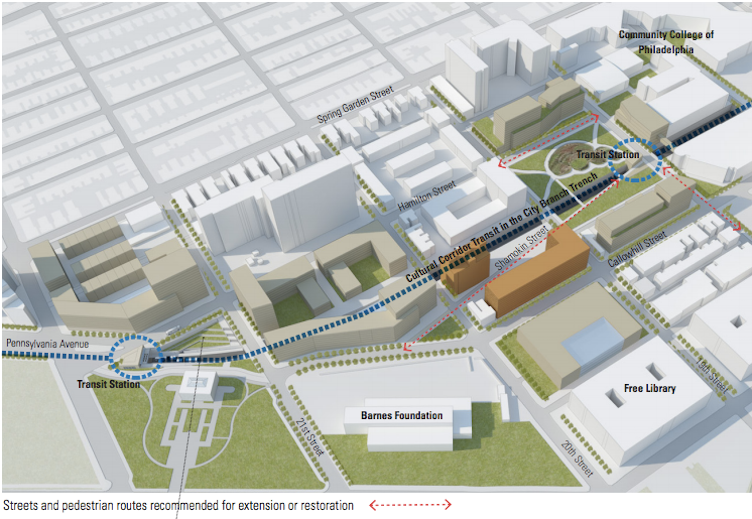

In its Central District plan adopted in 2013, the Philadelphia City Planning Commission called for turning the City Branch into a cultural connector, using buses to link the museums along the Benjamin Franklin Parkway.

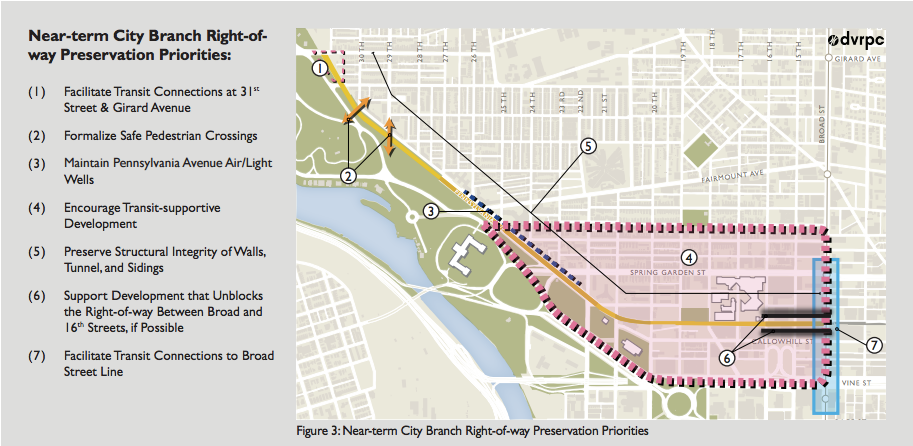

In 2015, the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC) studied that option, along with two others: Turning the City Branch into a below-grade, bus-only rapid transit corridor, or making it into a bus transit and trail line. All would have required SEPTA gaining ownership of the remaining sections of the City Branch and to remove the structural blockages that currently narrow the tunnel from 16th Street to Broad Street.

Those proposals, ranging from $119 million to $147 million, were deemed too expensive to pursue in the short-run. For all of them, the bulk of the money—around $100 million—would go to basic structural rehabilitation. That means the cost of any conversion into a linear park along the lines proposed by Friends of the Rail Park would start at $100 million. Fundraising for the first phase of the park took nearly a decade. That price tag: $8.8 million.

The DVRPC study concluded by recommending that the stakeholders involved—the City, SEPTA, and neighboring properties—take steps to maintain the City Branch’s viability for future transit use, which included the recommendation to “Pursue an Unblocked Right-of-way Between Broad and 16th Streets, if Possible.”

“In the long run, you can’t ignore how long it is, that it’s in an urban context, that it parallels Center City—it’s extremely valuable,” said Betsy Mastaglio, the DVRPC study’s author.

In the report, Mastaglio wrote that “because of the rarity of this urban infrastructure, and because of demographic and civic trends towards greater public transit investments, this report advocates a high-intensity public transit use in the long-term future.”

But if Radnor and CCP build this, that won’t happen, making it that much more less likely that the City Branch ever gets used for transit.

Mastaglio described the City Branch as “it’s a very unique asset in an old built up city.” Building new tunnels is massively expensive; New York City’s newly opened 1.6-mile-long Second Avenue Subway cost $4.45 billion. Philadelphia has a 1.75-mile tunnel just sitting around, waiting for a use. Putting a subway or underground trolley line there would cost much, much more than the buses, requiring deeper tunnels in most spots, plus digging out space for stations and a rail yard (or a connection to the Broad Street Line or the Route 15 Trolley).

Even if SEPTA had such an ambitious project in the works, the Broad Street Line extension to the Navy Yard, Norristown High Speed Line extension to King of Prussia, and trolley modernization overhaul all would stand ahead of it in line.

One of the reasons why not even the relatively cheap bus options made it beyond a cursory glance: current commuting patterns. The neighborhoods along the City Branch—Spring Garden, Fairmount, Brewerytown, and Strawberry Mansion—don’t have huge numbers of residents schlepping to Center City, with less than a third doing so.

Perhaps that looks at the issue backwards—maybe new transit lines would encourage the kind of developments that would lead to more commuters. That’s the trend historically—Philadelphia’s professionals first followed the streetcar to West Philly and up North Broad, then the railroad out to the Main Line. New transit stops drive up nearby real estate values; prices are already rising along NYC’s new subway line.

City Branch transit would mean gentrification along the line, and all the problems that come with it. But the worst effects could be mitigated, especially in light of the Philadelphia Housing Authority’s massive, $675 million, 1,200 unit project in Sharswood. Transit-oriented affordable housing developments like Paseo Verde in North Philly provide a template.

But besides a few planners and internet daydreamers, no one is pushing for such a coordinated development effort across disparate local government entities. SEPTA wants to put its limited resources into where people need to go now—like the Navy Yard and King of Prussia—not build in the hopes that later they will come. The DVRPC study acknowledges this: recommending denser development “that increases population and employment density” that creates demand for transit.

And therein lies the rub: Radnor Property proposing exactly the sort of dense, mixed-use development that city planners want/both the Planning Commission and the DVRPC recommended on that site: 600 multi-family residential units on top of 8,000 sq. ft. of ground floor retail.

Comati says SEPTA would prefer to offload City Branch, saying they would gladly support a rail-to-trails project that let it relinquish ownership. In the meantime, the transit agency holds onto it, managing its slow deterioration, and doing nothing to keep the long-term plans for the City Branch from deteriorating into little more than long-lost dreams.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.