Restoring ‘respect and dignity’ to 777 souls who died at Delaware psychiatric hospital and were buried in numbered graves

A 2016 monument identifying hundreds of previously unnamed graves near the Delaware psychiatric hospital is getting a facelift to better honor those buried there.

Listen 4:57

A stone angel stands amid the numbered graves in the Spiral Cemetery, with a view of the monument that has the names of the 777 people buried there. (Cris Barrish/WHYY)

Faith Kuehn leads the way through a field of high grass and leaves on the back end of the sprawling grounds of the Delaware Psychiatric Center a few miles south of Wilmington.

We’re careful not to tread on white granite cubes that jut out of the earth every few feet.

We’re looking for the grave of Nellie Sarkisian.

“Here’s 300,’’ Kuehn calls, noting the number inscribed in the granite as she searches for the right cube. “381. 382. 386. Yes, Here she is.”

We stand silently for several seconds in the warm sun and gentle breeze.

Kuehn is amidst 776 such cubes that are arranged in concentric circles in what’s now known as the Spiral Cemetery. A small and weathered stone angel with her hands clasped in prayer serves as a lone sentinel over the lost souls, many of whose cubes are invisible or can barely be seen under grass and weeds.

But beneath them are the graves of former psychiatric patients of what was once known as the Delaware State Hospital. Locals know it as “Farnhurst.” Patients without families who would or could afford to bury them were instead laid to rest on site.

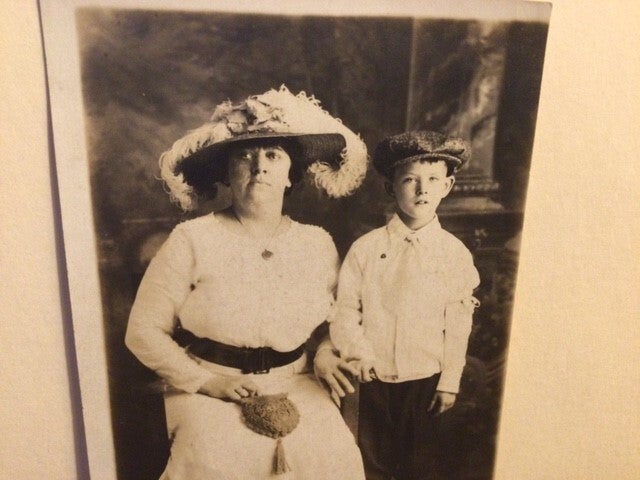

Sarkisian’s grandson, Philadelphia lawyer Dennis O’Connell, describes the site.

“When you see it for the first time, it stuns you, but that’s the way these people were regarded,’’ O’Connell told WHYY News. “There’s no names there. Just these little blocks with numbers.”

For Kuehn, restoring dignity to these long-forgotten souls has been a passion for the last decade.

She first learned of it while creating a garden on the grounds of the hospital, which is also home to several offices of the State Department of Health and Social Services.

She couldn’t see the nondescript graveyard at first, though. The field had overgrown and the cubes were not at all visible.

But she persuaded officials to create a memorial for the dead. That led to the creation of a monument for them in 2016. It’s a low-slung wall of tiles engraved with the name of each person and their marker number.

All were adults and were given a number upon their burial except for one stillborn child, a boy known only as Baby Crumblish. The baby’s mother was a patient who was later buried at a private cemetery.

“This is an opportunity to provide a measure of respect and dignity for people who probably struggled with that during their life,’’ Kuehn told WHYY News. “And there’s a very strong negative stigma about mental illness. So honoring the graves of these people is a way to try and diminish some of that stigma by saying ‘these graves here represent people who are part of the human family, just like you and me.’”

O’Connell, who is 74, only learned about his grandmother’s grave last year while stuck at home during the pandemic shutdown. He’s grateful for the monument that led him to her grave, which he first visited in May 2020.

It was a moving experience for O’Connell.

“I was thinking, this is the first time since 1929 anybody has gone there,’’ he recalled. “I have to admit it brought a tear to my eye, but I was so glad that I was able to do it. And I intend to visit at least annually at Christmas time.”

Restoring the memorial, as state begins burying again

When O’Connell returns this holiday season, he’ll see a revamped monument. It’s getting a facelift because it had deteriorated in spots, with many tiles coming loose.

“The tile was fired at the wrong temperature, and probably the wrong clay body on top of that,’’ says Michael Kalmbach. He runs the nonprofit Creative Vision Factory, whose artists made the tiles and constructed the monument five years ago.

“And so when that happens, you won’t know until you get through a season. Water gets absorbed into the clay, freezes, unfreezes, and then you’ll see like the front, the very top part will start to flake off.

Kalmbach’s clients are people who have experienced homelessness, with many suffering from mental illness and/or substance abuse. They work out of an art studio/drop-in center in downtown Wilmington.

The factory’s artists also made most of the new tiles for the revamped shrine, which has been reduced in size. Some of the tiles were also made by residents at the Hope Center, a refuge for people without permanent homes that was opened last year by New Castle County.

When a WHYY reporter visited the monument site, Kalmbach and Tim Austin scraped grout and used paste to attach tile.

Austin says the collaborations benefit the artists and society.

“I love working on these projects,” Austin said as he scraped away. “I think they do great things for the community and they bring people together and it brings the good out in people.

“They start discussions, you know. It gives people something to gather around and discuss and maybe educate and we could all use more of that.”

Kalmbach says this project has been mind-blowing. Just who was Caroline Roach, number 116? What about Arthur Robinson, number 774?

‘We had to chisel inches of concrete off every one of those tiles,’’ Kalmbach said. ”And the names. I mean, I could spend all day just like chewing on some of these names. And we always wonder, you know, what was their experience?”

Kalmbach says it’s been sobering as well, because the state now buries indigent men and women in the one-acre cemetery. A row of fresh graves is just steps from the wall. Soon those names will be added to it.

“We don’t have to worry or wonder about the conditions that these people live through,’’ he said. “We’ve been out here on the street level knowing what people have to suffer and endure, and the humiliation of just day to day life if you are outside. We’re starting to see this wave of a lot of the individuals that we serve – their health is eroding and they’re dying early.”

Kuehn calls the memorial a tribute to everyone who has at times struggled with their sanity.

She includes all of us in that category.

“We all have some of the same struggles in life,’’ she said. “It’s a big world with a lot of problems and it seems overwhelming at times. I think by honoring the dead you can honor the living at the same time.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.