Report: Thousands of pedestrian stops by Philly police illegal, racially biased

Listen 4:00

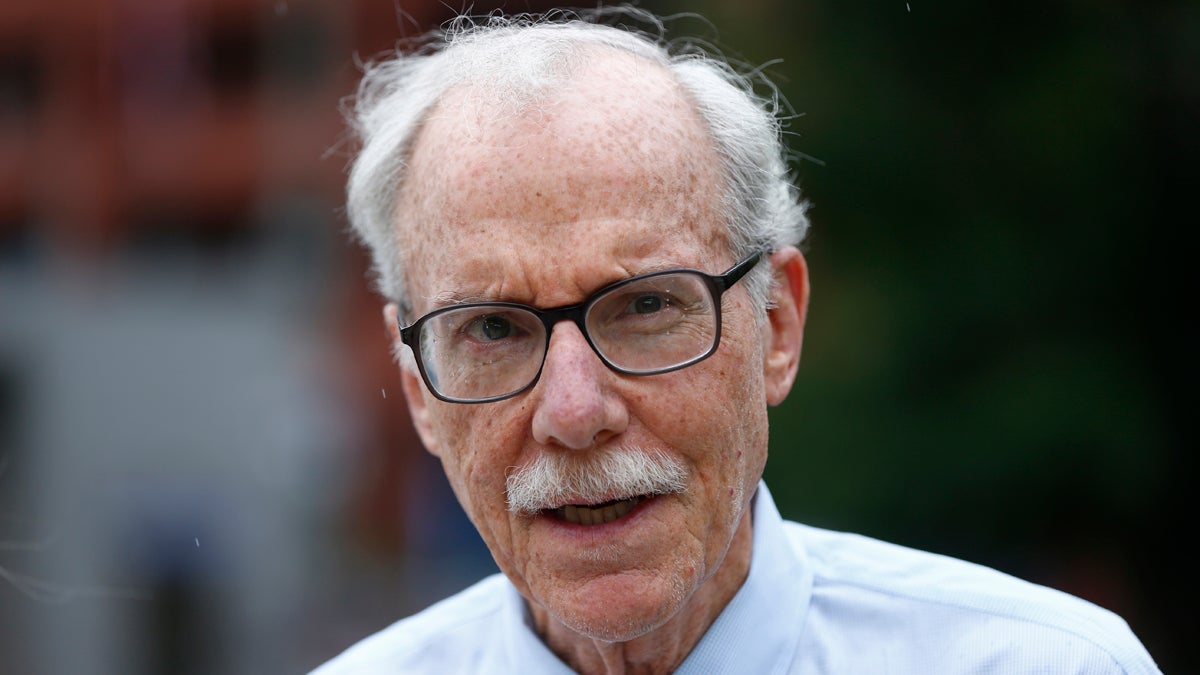

Attorney David Rudovsky says Philadelphia has made progress in reining in officers who ignore the city's stop-and-frisk guidelines, but more vigilance is needed. (AP file photo)

A third of the hundreds of thousands of pedestrian stops Philadelphia police officers conducted last year were done so illegally. More than half of the time, officers frisked civilians without having the legal right. Yet less than 1 percent of those pat-downs produced a weapon.

Black residents, by far, were affected by these practices more than any other group.

These are some of the findings of the latest progress report of the Philadelphia Police Department’s stop-and-frisk program, which has been overseen by a federal court monitor since 2012.

The latest report obtained by WHYY/NewsWorks, and set to be released Tuesday, shows almost no change from the year-ago data, something that’s intensifying concerns about how the city’s 6,600 officers interact with the community they’re sworn to serve.

“The city has failed to remedy serious flaws in the police department’s stop-and-frisk practices,” wrote civil rights professor of law at the University of Pennsylvania David Rudovsky in the report. “There is an immediate need for the mayor and police commissioner to ensure substantial improvements.”

Police Commissioner Richard Ross told reporters on Tuesday that the department is taking the latest report seriously.

“There’s some work for us to do,” Ross said. “Candidly speaking, the judge had some concerns,” he said. “But we have since then put measures in place to improve upon this.”

Rudovsky is representing the plaintiff in Bailey v. Philadelphia, the lawsuit that required the police department to file reports to a court monitor demonstrating the percentage of legal stops and frisks in the city. He argues the practice still violates the Fourth Amendment’s ban on unreasonable searches and seizures and the 14th Amendment’s guarantee that everyone be treated equally under the law.

“So we’re stopping thousands of innocent people. We have to counter that with at least an explanation as to why we’re doing that,” said Rudovsky.

Among the changes that the department will soon put into place: Captains will look at stop and frisks reports daily, instead of quarterly, and increase the auditing of the practice, Ross said.

The report, which is the sixth filed to U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, does show that the number of proper/constitutional stops rose by 4 percent, yet legal frisks slipped by that same percentage from a year ago. If there’s one take-away message, it’s that not much has changed since last year.

“It’s beyond a question of training and review. We’re now at the point of accountability,” said Rudovksy. “This won’t change unless officers and supervisors in the department who are not following the rules are held accountable.”

Some police commanders told the authors of the report that incident reports do not have a field for reasonable suspicion, a standard lower than probable cause that legally justifies a pedestrian stop. As a result, police say, many of the stops and frisks that raise red flags are the result of bad paperwork.

Rudovsky doesn’t buy this, writing that officers are defying the court order by not holding those responsible who conduct searches without suspicion.

“Unless officers and supervisors are held accountable, the current state of affairs will not change. The time for such action cannot be delayed,” he said.

Another sticking point is that officers, and their supervisors, who repeatedly engage in impermissible stops are not identified in any way, further blurring accountability, according to the report.

Mayor Kenney, who in his campaign for mayor promised unequivocally to end stop-and-frisk, released a statement taking a far more measured approach.

“The reforms that Commissioner Ross announced today are a tremendous step forward in Philadelphia’s community-police relations,” Kenney said. “They provide our officers with the resources and support they need to protect and serve, while also assuring all Philadelphians that there are very real accountability measures in place to ensure that oath is carried out.”

For a look at the impact the practice has on many communities, just talk to Arthur Shinholster, 58, of Germantown.

Around 7:30 p.m. on a recent Sunday, Shinholster was strolling out of a store holding grocery bags on his way to visit his grandkids in Southwest Philadelphia when he heard someone screaming at him.

“Get on the ground!” Shinholster recalls an oncoming officer yelling to him. “What do you mean, ‘get on the ground?’ I’m walking around with a three-piece suit. You wanna tell me to get on the ground. For what? Do I look like I’m gonna get on the ground to out? I don’t think so,” he said.

He said the officer told him that he matched the description of a robbery suspect in the area, though when Shinholster was shown the suspect’s photo, he said it looked nothing like him. The pictured suspect had curly hair and light-colored skin, he said. Plus, the person of interest was from Ohio, police told him.

“I ain’t never been to Ohio! I’m like, ‘yo, what do you want?’ He said, ‘What you got? What you got on you?’ I ain’t got nothing on me. He said, ‘Well, you know, we’re allowed to stop and frisk you.’ I was like, for real?”

Shinholster eyed up the radio reporter interviewing him and paused for a moment.

“You look suspicious. I’ll be walking around looking at you. I will stop and frisk you. Why? Because you got headphones, a microphone. Who are you?”

The 1968 U.S. Supreme Court decision Terry v. Ohio laid out the legal boundaries of a stop and frisk. What it boils down to is that an officer has the authority to investigate a pedestrian, and even pat down that person, as long as the officer has a good reason to believe that the individual might have committed a crime.

Opponents of the 8-1 decision say it gave police departments blanket authority to encroach on someone’s right to privacy, and — more cynically — imparted to cops the latitude to racially profile pedestrians.

But advocates of the ruling, including Philadelphia’s Police Department, argue that it’s an important type of proactive policing, insisting that it has thwarted crimes. They say that having probable cause for an arrest, or a search warrant, shouldn’t be the only times officers can interact with a suspect who could be armed and dangerous.

Former Mayor Michael Nutter was a longtime defender of stop-and-frisk. During his tenure, there was a falloff in violent crime and homicide dropped significantly from 391 in 2007, a year before Nutter came into office. During his term, total slayings hit historic lows of fewer than 250 slayings in 2013 and 2014.

It’s disputable, Rudovksy said, that there’s a direct link between ramping up the stop-and-frisk policy and the decline in violence. There is even less proof that these pedestrian investigations are taking weapons off the streets, he said.

In 2015, about one out of every 81 frisks produced a gun.

“Of course, only that one goes to court, and the judge thinks the cop had a sixth sense and can sniff out a gun,” he said.

The volume of stops hasn’t slowed since the court appointed an independent monitor over the program four years ago.

Some 200,000 Philadelphians were stopped and questioned by police last year, a number that has been pretty consistent over the years.

In New York City, which has more than five times as many people as Philadelphia, officers made just 24,000 street stops last year, down dramatically from the 685,000 made in 2011. Observers say that’s in large part due to a court monitor much like the one in place in Philly. Political will hasn’t hurt, either. Mayor Bill DeBlasio made his staunch opposition to stop-and-frisk a campaign issue in the city’s 2013 mayoral contest.

In Philadelphia, Mayor Jim Kenney has pledged to reform the practice, too, something that Commissioner Ross also supports. But Ross also admits that stop-and-frisk will never completely go away in the city since the country’s highest court affirmed the practice. Stop and frisk abuses, however, can indeed be corrected, he said.

“It is a law enforcement tool,” Ross said. “If you were to take that away from police officers, you would have chaos on the streets on this nation.”

The report was compiled by randomly auditing 2,380 stops from data provided by the department.

Although the city is about 43 percent African-American, 68 percent of stops and 77 percent of frisks involved black residents.

Latinos are 7 percent more likely to be frisked than their white counterparts.

“The outcome of those kinds of stops,” said Clem Harris, professor of African-American studies at Wesleyan University. “Increases the degree of aggravation and agitation particularly in the types of communities that are hard-hit by them.”

Most victims of crimes in Philadelphia are minorities, Ross counters.

“When people talk about neighborhoods being over-policing, well, where would you suggest we have them?” Ross said.

Plaintiffs sixth report to court and monitor on stop and frisk practices (PDF)

Plaintiffs sixth report to court and monitor on stop and frisk practices (Text)

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.