Privy contents become public during dig for Revolutionary-era museum

ListenIn the 18th century, Philadelphia did not have garbage collection. Everyone threw their trash down the outhouse shaft in back of the house.

Those privies are now goldmines of the archaeology world.

“You can learn a lot from people’s trash,” said archaeologist Rebecca Yamin. “All their secrets are in their trash.”

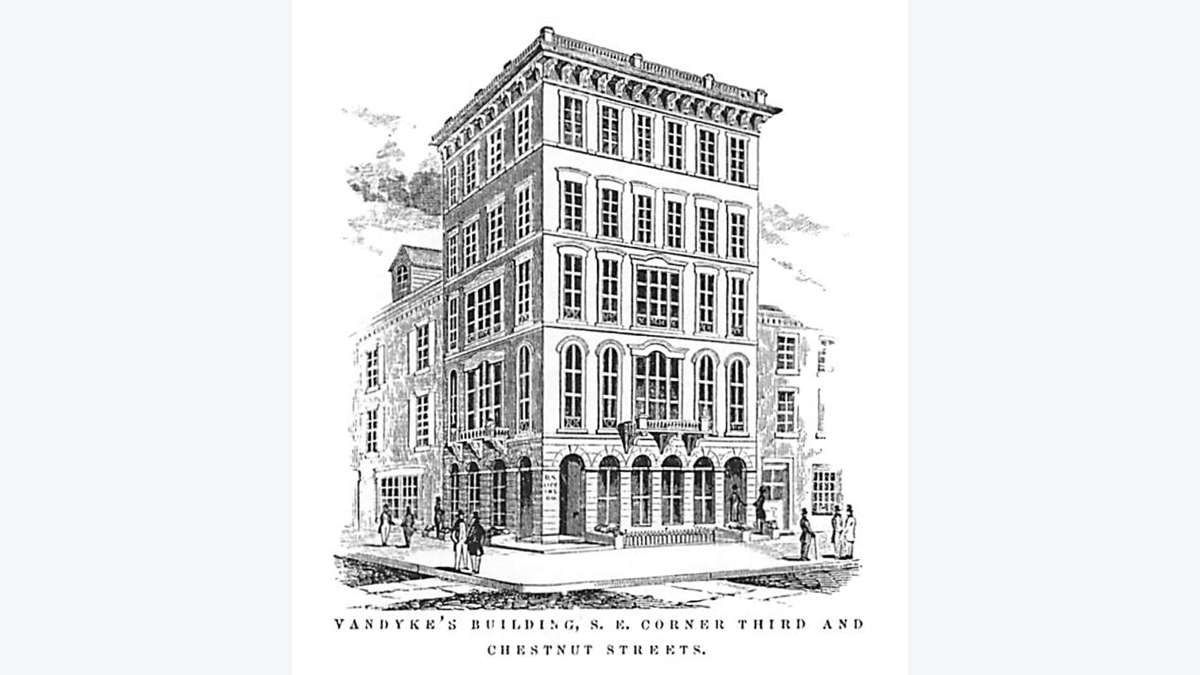

Yamin is the principal archaeologist monitoring the construction of the Museum of the American Revolution at Third and Chestnut streets in Philadelphia’s Old City neighborhood. It’s her job to stop construction of the facility expected to open next year when something of historical importance is unearthed.

Most of the time, her presence — required by law — is an annoyance to contractors working on a deadline. But what she found underneath the forthcoming museum turned out to be an unexpected treasure.

Among the thousands of objects found were pieces of pre-Revolutionary redware pottery, dating to the mid-18th century. With some digging, she and her team were able to identify the Colonial artisans who made them.

She also found beer tankards, drinking pots, and posset cups. “Posset was this horrible drink made out of curdled milk and alcohol,” explained Yamin.

Yamin and her team cross-referenced their finds against old maps of urban real estate. They knew who owned which lots, when they owned them, and what they were used for. Some were used for drinking.

“There was a lot of drinking going on in Philadelphia before the Revolutionary War,” said Yamin. “But the great part about that is that is where they were arguing the Revolution. They were arguing about politics, how do we get rich, what do we do, how do we live, how do we become Americans?”

Colonial-era speakeasy

The Colonists were not just going to bars to discuss the meaning of America.

Yamin discovered an illegal tavern operating out of the home of Benjamin and Mary Humphrey. The Humphreys’ privy had loads of objects suggesting a drinking establishment, and her team discovered records that the woman of the house, Mary Humphrey, was charged with running a disorderly house.

“A disorderly house was an unlicensed tavern that might have prostitutes hanging around,” said Yamin.

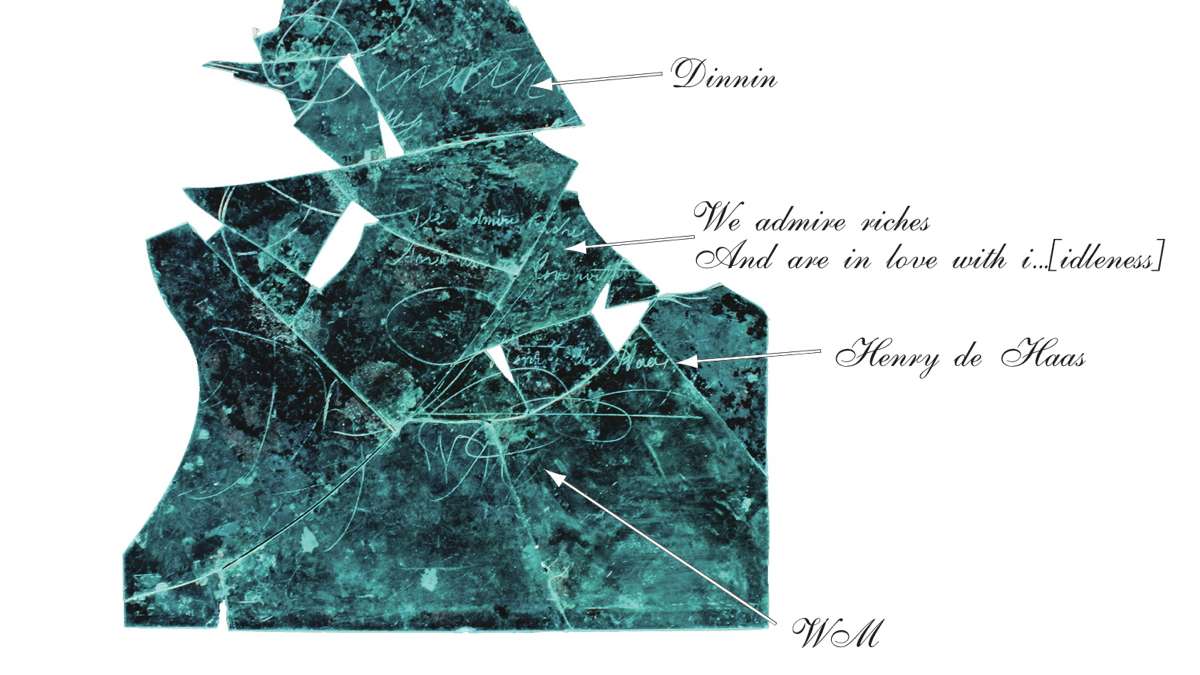

It was in the Humphreys’ toilet shaft that Yamin also found an object describing a more noble activity. Shards of a commemorative punch bowl, painted with a generic image of a ship with the phrase “Success to the Triphena,” were found.

The Triphena (or Tryphena, more accurately) was a merchant vessel that sailed many times between Philadelphia and Liverpool. In 1765, after England levied more taxes onto the Colonists with the Stamp Act, the Triphena carried a message from merchants in Philadelphia to merchants in England, asking them to urge members of the British Parliament to repeal the act.

Although repealed a year later, the Stamp Act spurred the Colonists toward revolution.

The poignancy that a piece of trash recovered from the site of the future Museum of the American Revolution could tell part of the story of that revolution was not lost on museum officials.

“Among the topics we will explore are methods of resistance the American Colonies developed to protest things like the Stamp Act,” said Scott Stephenson, vice president of collections and programs, who will include the reassembled punch bowl in the permanent collection.

The Humphreys, themselves, also will be remembered. The museum plans to create immersive environments, recreating a Colonial home, a tavern, and a soldier encampment. Objects owned by the Humphreys will be shown, as well as the story of their household slave, Quasheba, who was freed during the course of the war.

“There’s another revolution that’s very important to talk about through those objects,” said Stephenson.

Another iconic find

For Yamin, some of the most interesting things found had nothing to do with the Revolutionary War. While digging the basement for the museum, the construction crew found the original granite foundation of the Jayne Building, once the tallest building in Philadelphia.

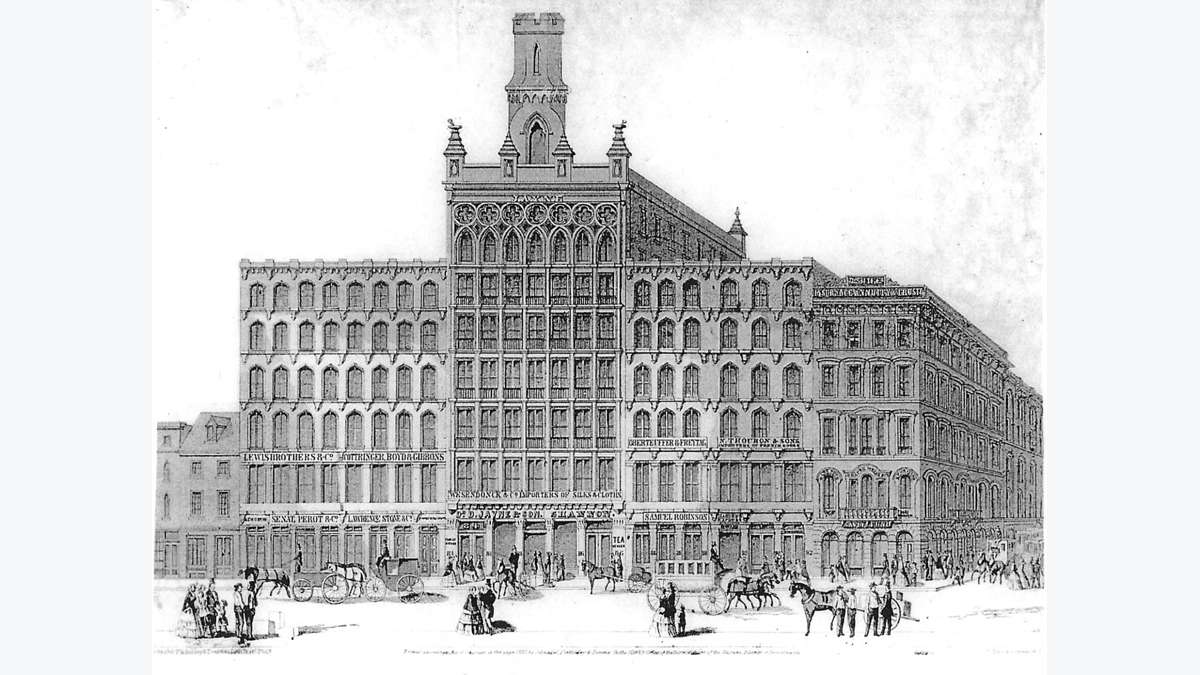

Built in 1850 by Dr. David Jayne, who made a fortune in patent medicines, it stood eight stories tall, topped by a turreted, Gothic tower. Built entirely of masonry, it predated City Hall by 44 years.

The Jayne Building played a vital role in the evolution of Philadelphia’s downtown real estate. Over 250 years, it changed from 18th century domestic and retail, to 19th century commercial and light industrial, to 20th century historic and institutional.

The building was torn down in 1954 to make room for the Independence National Historic Park visitor’s center over the protest of Charles Peterson, then the country’s pre-eminent architectural preservationist.

“Charles Peterson in the 1950s was the architect for National Park Service,” said Yamin. “He thought [the Jayne Building] was a prototype skyscraper, and that it should be preserved. But NPS only wanted to create a park that suggested the 18th century. They didn’t want anything from the 19th century.”

Now it will be preserved, in a sense. The granite foundation of the Jayne Building was pulled out of the ground to make room for the museum basement, and will be re-purposed as paving in various city parks.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.