Philly’s Spanish-speaking students lag in English language achievement

Listen 6:22

Dieba Sow, Jose Garcia and Minh Nguyen are immigrant students with the Philadelphia Education Fund's College Access Program (Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

This story is about an achievement gap.

No, not the achievement gap — a term used to describe how white and wealthy students perform better on standardized tests than minority and low-income students.

This is an achievement gap you might not know much about, even though researchers have puzzled over it for more than a decade.

This one has to do with language.

We’re writing about it now partly because it popped up in a recent Philadelphia study, with new data pointing to its distressing magnitude.

Earlier this year, the Philadelphia Education Research Consortium released a study looking at English learners — or ELs — who entered the district as kindergartners in 2008-09. It tracked their progress through the end of third grade because the city has a goal of ensuring all students can read on grade level by the beginning of fourth grade.

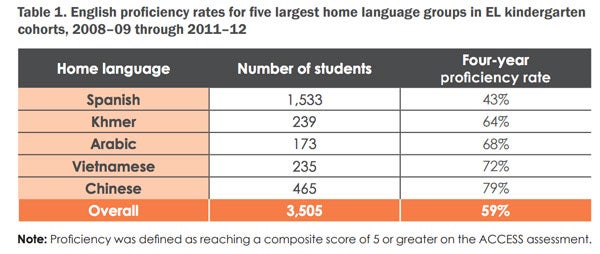

The study found a lot of interesting things, but one data point stood out. Here it is:

This chart shows about six in 10 students reached English proficiency after their first four years in the Philadelphia public schools. But, as you can see, that overall number masks huge discrepancies in who reaches English proficiency.

Students whose home language is Spanish were considerably less likely to reach proficiency than any other subgroup. And, on the extreme end, Spanish speakers were almost half as likely as Chinese speakers to cross that proficiency threshold.

It’s also important to note Spanish speakers are by far the largest group — by a factor of more than three. So we’re left here with a statement and a question.

Statement: Philadelphia’s largest subgroup of English learners aren’t mastering English as quickly as every other large language group.

Question: Why?

Before we get to the question, let’s note the phenomenon illustrated above isn’t unique to Philadelphia. Earlier this year, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine published a 415-page report on English learners. The report cited 12 studies — dating back to 2004 — that found this gap between Spanish-speaking ELs and other groups.

But even the academies seemed at a loss when trying to explain why.

“The reason for this difference is unclear,” according to the report. “But it could be due to multiple factors, such as prior schooling, culture, and family circumstances and characteristics.”

Ilana Umansky, a professor from the University of Oregon who is working on a paper that examines this trend, put it simply: “We don’t have a definitive answer to this question.”

We emailed or talked with about two dozen researchers, teachers, and students to hear how they would explain this trend. Predictably, there was no consensus. But we wound up with about four basic theories.

Theory 1: Family Income

This was one of the most common responses. Many folks said Spanish speakers were likely to be poorer than their counterparts from other ethnic backgrounds. Since it’s well established poor students face tremendous barriers to learning, we should expect Spanish speakers to progress at a slower rate.

It could be true Spanish-speaking ELs in Philadelphia are generally poorer than, say, Vietnamese-speaking ELs. But it’s unlikely family income totally accounts for the gap seen in PERC’s study.

“Certainly you need to control for [income] in your models,” said Umansky. “However, I don’t think it explains everything.”

No surprise, researchers studying this trend in the past have used income-based controls — such as whether a child qualifies for free or reduced lunch. Those researchers have still found Spanish speakers lagging.

Theory 2: Spanish saturation

There are nearly 150,000 Spanish speakers in Philadelphia, according to the American Community Survey. The numbers are even larger in New York City, which is where Jose Garcia arrived in 2012 after immigrating from the Dominican Republic.

Garcia moved to the heavily Hispanic Washington Heights neighborhood, and he says it were almost as if he’d never left. At home, he spoke Spanish. In school, classmates spoke Spanish. When he watched television, he often tuned into Spanish-language news.

“So it wasn’t like a big challenge for me,” Garcia said. “Because I speak Spanish, I used to hang with my people.”

Eventually, Garcia moved to Philadelphia and weaned himself off Spanish media by watching American movies like “The Fast and the Furious.” But he considers his early months in New York wasted time, compounded by the fact that many of his friends didn’t seem all that interested in learning English.

“They didn’t wanna learn it as fast because they didn’t need to use it,” he said. “They were speaking Spanish already. So they had a way to communicate with each other.”

Dieba Sow, a native French and Wolof speaker from Senegal, was thrown right into the linguistic fire when she arrived in Philadelphia two years ago. With no fellow French speakers around, she picked up English quickly — even if, at times, she needed Google just to decode the teacher’s instructions.

“You don’t want what’s easy,” she said. “You just want to learn and get it over with.”

All this points to a pattern Jeanne Devine sees in her EL students at Andrew Jackson School in South Philadelphia. Because Spanish speakers are such a large group, she says, they’re less likely to hear English or have to use it.

“My Chinese students will watch American television — which will actually, surprisingly to some of you — reinforce learning English,” she said. “Lots of things get learned through television. However, some of my Latino students will automatically go to the Spanish stations.”

When students return in the fall, Devine said, she can tell which students have been exposed to lots of English and which haven’t. Complicating matters is the fact that many of her Spanish-speaking students travel back and forth to their home countries.

“I have one little boy who worked so hard this year. He did a fabulous job. He came so far,” she said. “His mother is not an English speaker. And he’s going back to Mexico for the summer. My guess is he won’t hear a word of English all summer long.”

Devine saw this pattern play out a lot when she worked at Bayard Taylor School in Hunting Park. Most of her students at Taylor were Puerto Rican or Dominican, and she noticed many of them would shuffle between Philadelphia and their hometowns.

Taylor is in the heart of Hispanic North Philadelphia, long the city’s hub of Latino life. It sits in exactly the type of neighborhood where you might think a kid could speak Spanish exclusively.

But Nelson Flores grew up in nearby Olney, and he said that’s just not the case. In fact, he doesn’t think the Spanish-language achievement gap has much to do with language at all.

Theory 3: Segregation

Flores, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education, contests the notion that Spanish-speaking ELs aren’t learning English — at least in the way we typically understand language acquisition.

“We’re not talking about the ability to communicate in English,” Flores said. “We’re talking about the ability to do grade-level content in English.”

Flores believes a lot of the students counted as not being proficient in English can speak and comprehend the language with ease. Many of them, he believes, can speak English better than Spanish.

So why aren’t the testing as proficient?

The problem is with the test< Flores said. In Philadelphia, ELs take the ACCESS exam to determine whether they’re proficient in English. ACCESS tests speaking and listening skills, but 70 percent of a student’s score rests on how well they can write and read English. Flores believes many Latino students aren’t writing or reading as well as students from other language groups.

So why aren’t they writing and reading as well?

Flores believes it’s because Latino students are disproportionately living in isolated, high-poverty neighborhoods and learning in isolated, high-poverty schools.

High-poverty schools, Flores said, tend to receive fewer resources and less-experienced teachers. Plus, these schools have to deal with the compound effect of having so many students who experience trauma, transience, and the other disadvantages poverty confers.

Research out of California finds evidence for this theory.

We decided to take a cursory look at Philadelphia’s public school landscape to see if we could find traces of the same trend.

The graph below shows three groups of elementary schools. The schools in green have a higher-than-average percentage of Hispanic students and a higher-than-average percentage of ELs. The schools in red have a higher-than-average percentage of Asian students and a higher-than-average percentage of ELs. The schools in yellow have a higher-than-average percentage of Hispanic and Asian students, as well as a higher-than-average percentage of ELs.

Got that?

On the vertical axis, we chart the percentage of economically disadvantaged students at each school. Schools near the top have lots of children living in poverty.

On the horizontal axis, we plot each school’s SPR, a district-created measure that’s supposed to capture a school’s overall quality. Schools to the left score poorly. Schools to right score well.

Here’s the result.

As you can see, the Hispanic-leaning schools tend to perform worse and have higher concentrations of students in poverty. For Asian-leaning schools, it’s the opposite.

There are a number of potential explanations for this pattern. The U.S. has a long history of residential segregation. Patricia Gandara, a UCLA professor who studied this trend in California, also thinks there are more nuanced reasons for why Latino and Asian ELs end up in different types of public schools.

Gandara believes it has to do with why families immigrate in the first place. Referencing qualitative work done by one of her doctoral students, Gandara said Asian immigrants are more likely to come to America for the express purpose of advancing their children’s education.

“What my graduate student found in the study was that Chinese immigrants knew quite a bit about how to effectively get into the education system,” Gandara said. “This was a primary thing for them.”

Many Mexican immigrants, meanwhile, had little knowledge of how to best navigate the American education system or pick the best schools, Gandara said.

This may seem like a small consideration, but it points us toward theory number four.

Theory 4: Family background

If you look only at family income, you might assume many immigrant groups come from relatively similar socioeconomic backgrounds.

“Immigrants often look low-income because they’re in transition,” Gandara said. “They may have been physicians in their home country, but now they’re having to work as a cook.”

Many of the proxies we use to measure poverty or disadvantage trace back to how much money a family makes, but, in the case of immigrant groups, that data point may mask some crucial differences

A 2009 analysis led by Hunter College professor Donald Hernandez found, for instance, large discrepancies in the relative education levels of many immigrant groups. Adult immigrants from East Asia and the Middle East were among the most likely to have a high school or college degree. Adult immigrants from Mexico and Central America were among the least likely to have made it to high school.

Researchers Jennifer Lee and Min Zhou came to similar conclusions when they compared Mexican and Chinese immigrants. They found that, relative to their parents, the children of Mexican immigrants progressed further educationally from one generation to the next. But the children of Chinese immigrants progressed further overall, in large part because their parents started many steps ahead.

The logic here is pretty simple; parents who attended college are better able to help their children with homework or connect them to resources.

Minh Nguyen, a recent immigrant to Philadelphia from Vietnam, said his parents have been crucial to his educational progress. When Minh was in Vietnam, his parents paid for him to attend an excellent private school. Here, in the states, they continue to set high expectations.

“They read books. They had college degrees,” Minh. “So they wanted to pass that to me. And they set my mind when I was [a] really young age.”

Tip of the iceberg

These were just four theories we heard when we asked about the language acquisition gap. They weren’t the only four.

Many people pointed to societal biases against Hispanic students, arguing that teachers and administrators have lower expectations of them than Asian students because of deeply ingrained stereotypes.

Others wondered if the problem highlighted in the PERC report was even a problem at all. It’s not the speed with which children learn English that matters, they argued. Rather, the focus should be on the students’ ultimate grasp and mastery of the language by the time they finish school.

In many cities, ELs learn in bilingual or dual-language classrooms — instead of receiving all of their instruction in English, they receive some instruction in English and some in their home language.

Research shows this bilingual approach can benefit students in the long run, but could also slow them down in the short term since they’re trying to absorb so much language at once.

Philadelphia does have some dual-language programs for Spanish-speaking ELs, but not many. At present, only six schools provide Spanish-speaking ELs with bilingual or dual-language instruction. Since it’s such a small slice of the EL population in Philadelphia, it’s unlikely to have influenced PERC’s findings.

Where to go from here?

Right now, it’s hard isolate the cause of this gulf between Philadelphia’s Spanish-language ELs and everyone else. It’s possible — maybe likely — that all of these theories have some shade of truth to them.

In some kids, such as Alexs, you can find evidence for multiple hypotheses.

Now 11, Alexs was born and raised in South Philadelphia. (We’re withholding his last name at the family’s request.)

Even though he was born here, Alexs didn’t start to learn English until he entered kindergarten. It wasn’t always easy, but Alexs found friends to help him. Around age 8, he started watching local news so he could better grasp the language.

“My teachers were like you changed a lot after third grade,” Alexs said. “All A’s, B’s.”

When Alexs speaks, he sounds fluent, and there’s little trace of an accent. He does, however, continue to struggle with reading, he said. Right now, abbreviations seem to trip him up.

Alexs’ dad — a cook from Puebla, Mexico — can’t always help him with his work. But his dad was able to connect with a neighbor who tutors Alexs in reading. His family wants Alexs to master the language and prosper here in America.

“Because there’s not a lot of money in Mexico — not a lot of possibilities,” he said.

Here, Alexs believes, is where the opportunities are. And learning English is key to unlocking so many of them.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.