Philly school knew about toxic lead in drinking water but kept parents in the dark

Recent testing uncovered high lead levels in the water at Mastery Frederick Douglass Elementary. Parents say they should have been told sooner.

Listen 4:34

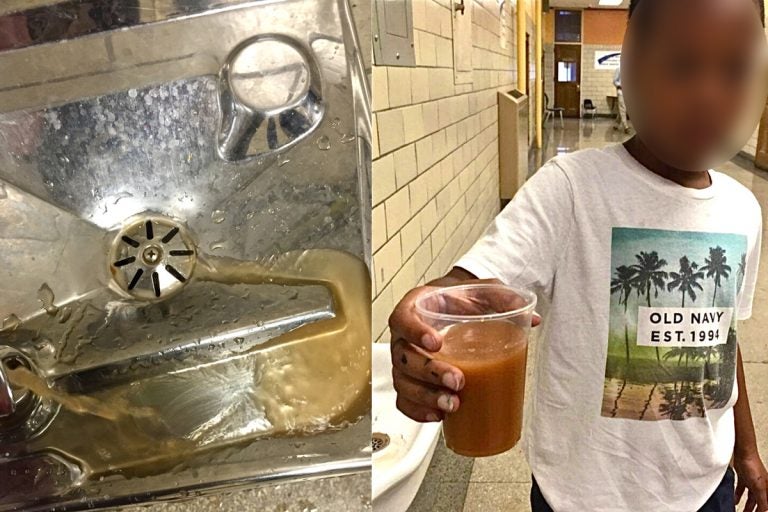

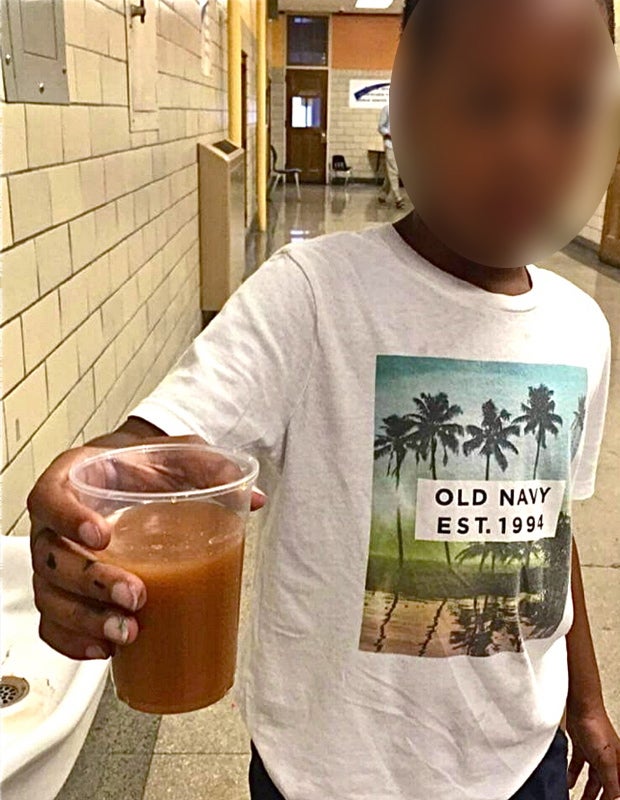

Photos taken by two former teachers at Frederick Douglass Mastery Charter School show water drawn from drinking fountains at the school in June of 2016. (Photos provided)

It was a display of kindness that should have been heartwarming. Instead, Frederick Douglass Elementary School teacher Alison Marcus just felt queasy.

In 2016 — while headlines blared about the water crisis in Flint, Michigan — Marcus’ North Philadelphia charter school raised money to buy bottled water for residents of the distressed Midwestern city. But as she watched students at the charter, run by Mastery, toss change into a large plastic bucket, she felt a pang of guilt.

“I just remember thinking, ‘We should definitely be testing the water here,’” she said in an interview this month.

That’s because Marcus says she and other teachers feared the drinking water at the school wasn’t much better than Flint’s. That same year, for roughly a week, some hallway fountains and sinks spurted a brown liquid that looked more like apple cider than water, according to nine former and current staffers.

Administrators say they were unaware of the issues. However, Marcus says she and others complained about the brown water in 2016 to school leaders. No one ever formally notified parents.

In the coming years, there would be a stream of other warning signs that something was gravely wrong with the school’s water system: Water fountains and sinks failed lead tests in 2017; a staffer reported cloudy drinking water in 2019; and more lead tests a few months later showed off-the-charts levels of the neurotoxin at some fountains. But Mastery repeatedly failed to notify parents expressly and expediently about these results.

The most recent lead test came in April, after City Council legislation required schools to conduct independent water quality tests. While the School District of Philadelphia’s threshold for allowable lead levels in water is 10 parts per billion (ppb), lead inspectors found a water fountain on the second floor of Douglass that had lead concentrations at more than 1,700 ppb. Another fountain on the third floor hit 3,500 ppb, roughly 350 times higher than the district limit.

Mastery says it quickly shut off the water supply to the affected fountains and posted on its website a copy of the 218-page water quality report, from New Jersey-based Smithco Engineering, for all of its 18 schools in Philadelphia.

To understand the potential gravity of the situation, parents would need to find the link to the report amidst the school’s nutrition plan, its snow day policies and a dozen other public notices.

Mastery did not directly communicate information to parents about the failed lead tests until last week after inquiries from this joint Keystone Crossroads/PlanPhilly investigation. The email lacked specifics about lead levels and came nearly eight months after water samples were first drawn.

“Wow. That’s totally not right,” said Michelle Brewton, parent to a Douglass fifth-grader, upon learning of the details from a reporter on Tuesday. “For there to be lead in the school where children go and drink water, and the parents are not notified…. I was not aware of this.”

Gale Glenn, a mother of three Douglass students, expressed anger that the school had not been more proactive in disclosing the water quality problems at the school.

“They have my email. They have my phone number. They call me for every little thing my children do,” she said. “You can’t call me about the important stuff?”

Mastery CEO Scott Gordon now says the school should have notified parents that their children may have been exposed to unusually high levels of lead contaminants.

“We should have sent a notice home at that time,” he said in a phone interview Wednesday. “In general, our policy should be if there’s something that a parent is concerned about, we should notify them. I’m not clear why that notification didn’t go out at that time.”

Mastery officials said this week that all drinking fountains at the school have been decommissioned. Students get filtered water from portable jugs.

Kevin Schnepel, a Ph.D. with Simon Fraser University who has studied the impact of lead on childhood development, said exposure is linked to learning delays, higher rates of ADHD and other behavioral problems. He said that the growing scientific consensus is that there are no safe levels of lead exposure, particularly for children under the age of six.

“There is a lot of important neurodevelopment happening up to the teenage years. It’s bad to be exposed at any age. But it’s particularly bad at a young age,” Schnepel said.

He said the failure to immediately notify parents about the possibility of prolonged exposure to high levels of lead was especially troubling because the damage to brain development could be exacerbated without blood testing or treatment.

“I don’t want to say that it’s criminal,” Schnepel said. “But it’s a travesty when you have information about individuals that are being put at risk in terms of their cognitive and behavioral development and they don’t know about it.”

13 years of warnings

While Douglass’ level of contamination may be an outlier, it is unclear if the response to these alarming reports is unusual. Across 13 years and three school operators, no one seemed to grasp that the school had a systemic water issue — and that parents should have been made unmistakably aware of it.

Katie Romoser had only been at Douglass for a couple of weeks in 2015 when she says a Mastery administrator saw her filling her water bottle at one of the school’s antiquated, porcelain water fountains. The administrator told the newly minted special education teacher that she shouldn’t drink the water from the hallway fountains. Instead, she should use filtered coolers set aside for staff.

“I kinda looked at him and was like, ‘Isn’t this the water that the kids drink,’” Romoser recalled.

The then-22-year-old remembers feeling stunned and confused — perhaps this was simply the way of the world in an old school building. She started sneaking kids water from coolers in the staff lounge.

“I didn’t want to be seen as a dramatic new teacher that was causing problems,” said Romoser.

The binary system of staff coolers and student water fountains preceded Romoser’s arrival at Douglass and Mastery’s involvement in the school, although no one could say for sure when separate water sources first popped up in staff areas.

It is clear that almost none of the current Douglass students were born when the first signs of toxic water surfaced at the North Philadelphia school, which sits in one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods, where levels of lead exposure in children are high, according to city data.

The district ran the Art Deco school building from its construction in 1938 until 2010. SDP administrators first began a 10-year campaign to test some 30,000 water outlets inside city schools in 2000. Records suggest tests at Douglass took place between 2000 and 2007.

The results included 10 individual water samples containing lead concentrations at 100 ppb or higher, and one sample with lead levels at 4,710 ppb.

The failed outlets included drinking fountains. A district spokesperson said that by 2007 the district had “remediated” and retested all remaining outlets to ensure they were safe for drinking.

Douglass passed out of district control nine years ago as part of the Renaissance initiative, where charter operators take over neighborhood schools in hopes of spurring better student outcomes. The district initially contracted with a charter network called Scholar Academies to run Douglass. It’s unclear if the organization knew about the troubling water tests a few years earlier.

Attempts to reach then-CEO Lars Beck were unsuccessful. Teachers from the era recalled fading spray-painted signs above school sinks warning people not to drink the water.

When Scholar Academies failed to earn a charter renewal from the School Reform Commission in the spring of 2015, Mastery took the baton. Like its predecessor, the school used the Douglass building with district permission and agreed to oversee day-to-day operations of the school.

As Mastery’s first year at Douglass came to a close in June of 2016, former staffers say the school’s water suddenly turned brown. Nine former and current employees independently confirmed that brown water spewed from fountains and sinks for a period of about a week at the end of the 2016 school year.

“That was shocking,” said one former teacher, who declined to give her full name but provided a photo she’d taken of a student holding a cup filled with brown water. “It was disgusting that we would have students actually drink from these fountains.”

It’s unclear exactly how Mastery staff responded to that incident. Some teachers recalled water being shut off for several days, others said they were emailed instructions to keep children away from water fountains, others said a staffer posted more handmade signs warning students not to drink the water.

Former Douglass staffer Alison Marcus, who now teaches at another school in North Philadelphia, said the discolored water persisted for nearly a week, even after administrators initially claimed it had been fixed.

“I had walked a student to the water fountain and used it. The water that came out was still brown,” said Marcus. “I took a picture and sent a text to my principal.”

None of the teachers interviewed for this story recall school leaders reaching out to parents after the alleged discovery of brown water.

“I applied this to the long list of things that wouldn’t happen in white schools,” said former teacher Katie Romoser, alluding to the fact that nine in 10 Douglass students are African American and live in poverty. “I knew that it was wrong. I knew that other teachers and administrators knew that it was wrong.”

The elementary principal at the time — who left Douglass in November 2016 — said he has no memory of the alleged incident.

“I don’t have any recollection of that or any issues like that being brought to my attention,” wrote then-principal Tom Weishaupt in an email.

Mastery CEO Scott Gordon said he did not recall the brown water incident, either. He said the administrator who could confirm or deny the details was unreachable this week.

Discolored water is not itself evidence of lead, said Jerry Roseman, director of environmental science for the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers’ Health and Welfare Fund. But he believes it should have been a warning sign.

“You should think of it as kind of a visible flag, a sentinel event, warning you, ‘Hey, we have a problem here,’” said Roseman.

‘Top priority’

Mastery has never voluntarily initiated any water testing at Douglass, but the Flint crisis did cause the school district to do its own reconnaissance. The district, in 2017, retested water outlets at all of its schools, including buildings it owns that are used by charters. Once again, the lab work signaled something amiss about the water quality at Douglass.

A report found that at least three outlets at Douglass exceeded the district’s lead safety threshold of 10 ppb — although at much lower levels than prior or future tests would find, with the highest reading at 29 ppb.

Of the 165 elementary and middle schools tested, Douglass was among 27 to have three or more unsafe water outlets. Mastery says it responded promptly by taking all three outlets offline. It then sent a letter — required by the district — home to Douglass parents once students returned from summer break, about two months after getting the results.

The charter operator, it seems, was unaware of the fact that the school had now failed two lead tests in less than a decade. If the district was concerned with this red flag, they took no special action to address the issue.

Still, more warning signs emerged over the next two years. A comprehensive facilities review of all district-owned facilities released the same year said that Douglass should replace its water fountains as the school’s pipes “may contain” lead solder. Including Douglass, 20 schools received warnings about lead solder in pipes — a joining method banned in new construction by updates to the Safe Drinking Water Act in 1986.

Then, in January 2019, according to Mastery, a teacher noticed “cloudy” water in one of the school’s drinking fountains. The school immediately shut off that fountain after the report, a Mastery spokesperson said, but did not notify parents.

Between March and April 2019, Mastery tested the water at all of its Philadelphia schools, as required by a new city ordinance. For the third time, the results of a water test pointed to problems at Douglass.

Of the 18 Mastery schools tested, Douglass was the only one where four different outlets came in above the lead safety threshold established by the school district. Across the entire Mastery network, there was only one other sample that registered above 300 ppb. Douglass alone had three such samples, all from drinking fountains

CEO Gordon said that the school disabled all of the affected fountains days after the lead results were delivered on April 17, and posted signs warning students about the outlets.

“The safety of our students, our staff, our families is our top priority,” he said. “If there was suspicion of water quality issues, our protocol would be to turn off the water, investigate and keep the water off permanently or address the problem.”

At some point this year — Mastery officials could not say precisely when — all of the remaining fountains at the school were also taken out of service and replaced with water coolers.

Gordon underscored Mastery’s compliance with new lead testing initiatives and actions taken to shut off access to contaminated water. But the CEO now says he regrets failing to disclose the scope of the problem to parents earlier.

In response to reporting by Keystone Crossroads/PlanPhilly, Mastery now plans to hold an information meeting in the coming days with Douglass parents to discuss the lead issue and it will host a fair about environmental problems in schools.

A more comprehensive solution may be around the corner. Gordon says he is now investigating ways to completely remediate or replace the water supply infrastructure at the school.

‘Protect my kids to the fullest’

Parent Alfonso Glenn believes the problems at Douglass are symptomatic, not isolated. He thinks that, unfortunately, plenty of other school leaders have — or would have — handled the lead situation at Douglass much like Mastery did.

“I’m quite sure it’s not just Douglass,” said Glenn. “It’s probably every school in the city of Philadelphia.”

The school district admits it has a maintenance backlog so long it would cost billions to clear. Water issues at one school must compete for attention and resources with asbestos, chipping paint, failing HVAC systems, and other hazards caused by the city’s aging infrastructure.

Addressing Philadelphia’s systemic lead problems — and the harm that exposure can leave on children — will likely take years of tests and mountains of money. What Douglass parents want in the meantime are school officials who will be up front when problems arise.

“When you don’t know, you can’t protect your kid,” said Stephanie Williams, parent of two students who attended Douglass for six years. “And that’s what it really comes down to. I felt like I wasn’t allowed to protect my kids to the fullest.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.