Just one third of elementary classrooms in Philly meet minimum ventilation standards

Our analysis shows one-fifth of city elementary schools don't have a single classroom that can accommodate 15 people while meeting air circulation standards.

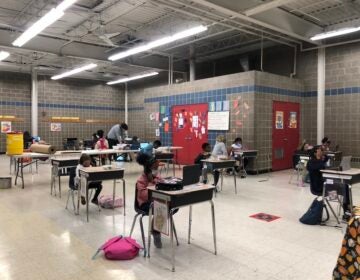

William Dick School in North Philadelphia does not fare well in meeting the district’s minimum ventilation standards. (The Notebook)

As thousands of Philadelphia parents weigh whether to send their children back to school buildings, a WHYY/Chalkbeat analysis of school air quality evaluations has found that two-thirds of elementary classrooms with completed reports lack even the minimum industry-recommended ventilation standards to safely hold 15 or more people.

And one-fifth of elementary schools have no classrooms that can accommodate that many people while meeting the air circulation standards.

Under the district’s hybrid plan, about 32,000 students in kindergarten through second grade would have the option of returning to school two days a week, with half the group attending on Mondays and Tuesdays and the other half on Thursdays and Fridays, starting on Nov. 30. Staff members are expected to start preparing their classrooms on Nov. 9, less than two weeks away. Parents must decide by Friday whether to send their children back.

Our analysis is based on 79 reports that are available on the district’s website, out of 119 that officials say have been sent to principals. There are 147 elementary schools and 215 district-run schools in the city. The reports online are for 74 elementary schools and four high schools that house pre-kindergarten programs — Edison, South Philadelphia, Lincoln, and Washington, plus the Rivera building, which is a district office and conference center that houses a private pre-kindergarten program.

District officials have not explained why all 119 of the reports distributed to principals are not also available online.

The school district has had problems with air quality and ventilation in its buildings for years, an issue that has become magnified during the coronavirus pandemic. Transmission of the virus is believed to be higher indoors, and school buildings, unlike hospitals, weren’t designed to mitigate the spread of a contagious disease.

The standards used in these reports — 15 cubic feet per minute, or CFM, of airflow per person in a room — are general ventilation requirements, not those that experts say are sufficient to curb the spread of an airborne pathogen. Even by the lesser non-medical standard, an earlier analysis found 80% of school buildings had some ventilation problem.

In doing school-by-school, room-by-room evaluation of air flow, the district is trying to find out where its ventilation problems are the most egregious and assure that the classrooms being used have acceptable air circulation, while counting on social distancing, sanitation, hand-washing, mask wearing, and other safety measures to control virus spread.

Assuring the 15 CFM per-person standard “is just a piece of the puzzle,” said district chief operating officer Reginald McNeil. The other safety measures are “what helps lower the risk” of COVID-19 transmission.

For its analysis, WHYY/Chalkbeat counted which classrooms would be safe for up to 15 students. That figure was chosen because the maximum class size under the teachers’ contract for the pre-kindergarten through second grade classes is 30 students, and under the hybrid system, no more than half of them would be in school on any given day.

National data suggest schools aren’t major sites of virus transmission, especially in the earlier grades. Outbreaks have been relatively rare as schools have reopened across the country. But an important aspect of safely reopening schools is community spread. Children can spread the virus, and in communities with high rates of COVID-19, it can be difficult to limit transmission.

Philadelphia’s positivity rate for the past seven days is 7.3%, the highest since early June, and it has been rising.

Every week, the state Department of Education rates each county based on the severity of viral spread and offers guidance about whether schools should stay virtual, could move to a hybrid model or fully reopen. Last week, it moved Philadelphia from the moderate to substantial risk category, which recommends all-virtual school.

Ventilation problems in aging school facilities have raised concerns for parents and educators about how COVID-19 might spread.

The lack of public information available also has made it difficult for parents trying to make an informed decision. As of now, reports are available only for about half the buildings that house the lower grades, and the district doesn’t plan to release the rest until Nov. 12, after Friday’s deadline.

Parents have been told that if they choose this week to send their children back to the buildings, they can change their minds at any time. The reverse, however, is not true: If they choose all-remote, they will not be able to return to school in person until the third quarter, in late January.

In weighing their options, parents are trying to decipher reports that are technical, confusing and, in some cases, seem to indicate that no parts of the building have what is considered adequate air circulation, or “air balancing,” in which there is continual cycling of indoor and outdoor air.

“I’m looking at a sheet with numbers with no other information on it,” said Lisa Hallowell, an environmental lawyer with a third grader and a kindergartner at the McCall School in Society Hill. “They’re asking for us to make a pretty big decision for all of our families and we just don’t have great information and we don’t have a lot of time to digest the information that we have.”

She said that the report for McCall showed that in her daughter’s classroom, “the occupancy allowed…was zero people.”

At William Dick Elementary in North Philadelphia, the “safe occupancy” level for all classrooms is listed as zero — likely meaning that there is no indoor-outdoor air circulation in any classrooms. At A. L. Fitzpatrick Elementary in the Northeast, which has 80 pre-kindergarten students, no classroom is adequately ventilated for more than four people at a time, according to the reports.

Three other pre-kindergarten sites — Edmonds, Kelley and Meade — don’t have even one classroom that can safely house 15 or more students, according to the reports.

And then there are other schools, like Richmond Elementary in Frankford, for which there are no reports yet at all.

“I am concerned because our ventilation report has not been completed,” said Stefanie Marrero, a mother of four with three students at Richmond, including a first grader. Parents, she said, are “left in the dark … I want a copy of this report, I want to know if my kids’ school is safe to be in.”

Hallowell said she has decided to keep her kindergartner home. Marrero is inclined to sign up her first grader for the hybrid approach while she waits for more information.

A technical breakdown

Philadelphia school buildings, with an average age of 75, have longstanding issues with ventilation and air quality. Teachers have long complained about needing to open windows in the winter because the heaters were on overdrive — or conversely, they had to keep their coats on because the heat didn’t work. And the last time the district tried to open in late August, it had to close schools because of stifling conditions. While some schools have air conditioners, many don’t. In some buildings, windows can’t open or can open only a little bit.

Other school districts, such as New York City, rushed to purchase air purifiers and test and repair ventilation systems this fall. Since the 2017 study of all its school buildings, Philadelphia has invested in upgrading systems. The pandemic has accelerated this work.

“Because of the pandemic, we’re taking a deeper look into our ventilation systems now,” said chief operating officer Reginald McNeil in an interview.

The district’s capital projects plan indicates that it intends to spend more than $150 million on recommissioning or replacing heating, ventilation, and cooling systems in 20 schools from 2020 to 2026.

McNeil said that 17 elementary buildings, and 25 schools overall, have non-functioning ventilation systems that could not possibly be repaired in a month. Principals know which buildings, but they have not been publicly identified.

For these schools, McNeil said the district is planning to use window fans that can circulate outside air into the building. The fans do not have an air filtration system, he said, but they do have a rating for how many cubic feet per minute of fresh air they circulate in a room.

“But just because the ventilation systems aren’t functioning doesn’t mean you can’t use the building,” he said. In fact, most district schools did not regularly use their ventilation systems, which consist mostly of large house fans that bring outside air into a room.

Before the pandemic, he said, most ventilation systems “were not even turned on in schools.” Schools could be heated, “and when it got too warm, you would open a window. Because of the pandemic, we’re taking a deeper look into our ventilation systems now.”

WHYY/Chalkbeat also asked two air quality experts to evaluate the reports and explain what they reveal to parents and teachers about effectiveness in stemming the spread of COVID-19.

“The 15 CFM per person is intended to be good for everyday aesthetic complaints,” said industrial hygienist David Krause, citing the ability to mask body odor and regulate moisture levels. “This is irrelevant when it comes to pathogen control.”

In general, he said, “Schools are not built to do this.”

He said hospitals require at least six, preferably 10, complete “air changes” per hour, meaning outdoor air replacing indoor air. Even the classrooms with the best results would not come close to meeting that standard, he said.

The numbers in Philadelphia’s reports only “tell part of the story,” said William Bahnfleth, an engineering professor at Penn State University and chair of the new epidemic task force of the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, or ASHRAE.

The district, he said, is to be commended for its “attempt to make sure the minimum ventilation rate is provided.” But for pathogen control, “that rate is not considered sufficient by ASHRAE. What you need is minimum ventilation, plus filtration.”

“But minimum ventilation without additional air cleaning probably is not sufficient protection,” Bahnfleth said.

Even before the pandemic, 41% of school districts in the country needed to update or replace their heating, ventilation, and air conditioning, or HVAC, systems in at least half of their schools, according to a report released in June by the U.S. Government Accountability Office. That’s about 36,000 school buildings nationwide.

“Now we want those systems to protect students and staff from COVID-19,” Bahnfleth said. “That’s a concern.”

Both Mayor James Kenney and city health commissioner Dr. Thomas Farley take the position that it is safe to reopen schools for the youngest learners, citing scant evidence of classroom spread in some 50 Catholic, private, and charter schools that have already returned to in-person learning. At a press conference last week, Farley attributed an outbreak at the private Philadelphia School to a one-time safety lapse.

The district’s ventilation reports were completed by several vendors. Most reports list the room number and type of room — classroom, office, auditorium, gym, hallway.

The reports also indicate the amount of outdoor ventilation that a given room receives. As a result of the standard of 15 cubic feet per minute of ventilation for each person in the room, , the district’s contractors divided this number by 15 to determine maximum occupancy levels.

Lewis also emphasized that the district is doing a square-foot analysis of each room to determine safe occupancy based on social distancing requirements, and the lower number would be the limit in a given room.

The Philadelphia Federation of Teachers has raised concerns about school ventilation.

The Caucus of Working Educators, an activist group within PFT, released a report on Tuesday based on its own analysis that said 66% of all rooms were unsafe for 10 students and one teacher, and 74% were unsafe for 15 students and one teacher. Its report also said 96% of bathrooms, 60% of nurse’s offices, and 58% of hallways and stairwells were unsafe for any occupancy, even before the pandemic. In total, the Caucus found that 1,700 rooms across all schools were unfit due to a lack of adequate ventilation.

Despite concerns, the district’s reopening readiness dashboard said 53% of schools are “fully certified for ventilation,” as of Wednesday. But Lewis said that ventilation “certified” means an air balancer has examined the school “and we have the results,” not that those schools had been cleared for safe occupancy.

Parents voice their concerns

With a Friday deadline looming, some parents will be forced to make a decision about sending their children back to school without air quality reports. District officials have said they don’t plan to release the remaining reports until well after that deadline, but are giving parents the option to change their minds if they choose hybrid and then are unnerved by the report for their school.

Parents also are concerned about whether the district can address basic safety and sanitation issues before schools reopen.

Kaija Sannicks, 31, of East Falls quit her job to keep her preschooler home. Her four-year-old is enrolled at Thomas Mifflin Elementary.

“They have problems keeping toilet paper in the bathrooms,” she said. “You really want me to trust that you’re going to keep my child safe from a highly contagious airborne disease? No, no.”

There’s not an air quality report for Mifflin yet, but she said it wouldn’t matter.

Richmond Elementary, where three of Stefanie Marrero’s four children attend, also has had an asbestos problem. Her oldest is at Kensington CAPA. Marrero, who was protesting last January over the asbestos with other Philly parents, teachers, and union leaders, said it’s “very hard” to trust the school district.

“Our school was one of the worst,” she said about the asbestos. “How do you expect K-2 to come back in without proper [personal protective] equipment and without ventilation, no fans, no air conditioners? How do you expect to teach children?”

Marrero plans to send her first grader back to hold his spot while she waits for Richmond’s report.

But she remains torn about what’s best for her family.

“Do I want my child to sit in a classroom for seven or eight hours with one teacher, and they can’t get up, there’s no recess, and still have lunch at your desk,” she asked. “Or should I keep him home where he can get up and move around — do I want that headache still? I don’t know. Because I have to deal with three other children. It’s very complicated.”

Get more Pennsylvania stories that matter

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)