Philly joining private-led initiative to reduce commercial building energy use 50% by 2030

In a policy framework for advancing green building in Philadelphia published in January, the Delaware Valley Green Building Council (DVGBC) announced that it’s leading the formation of Philadelphia 2030 District, a private sector-led initiative to reduce energy use, water consumption, and transportation-related emissions from the building sector 50 percent by 2030 at a district scale.

By doing so, Philadelphia will be joining Los Angeles, Toronto, Pittsburgh, Austin, San Francisco and 10 other cities participating in 2030 District, a project that already covers almost 300 million square feet of new and existing commercial building space.

“This is a strategy to mitigate climate change, ultimately,” Katie Bartolotta, DVGBC’s policy and program manager told PlanPhilly.

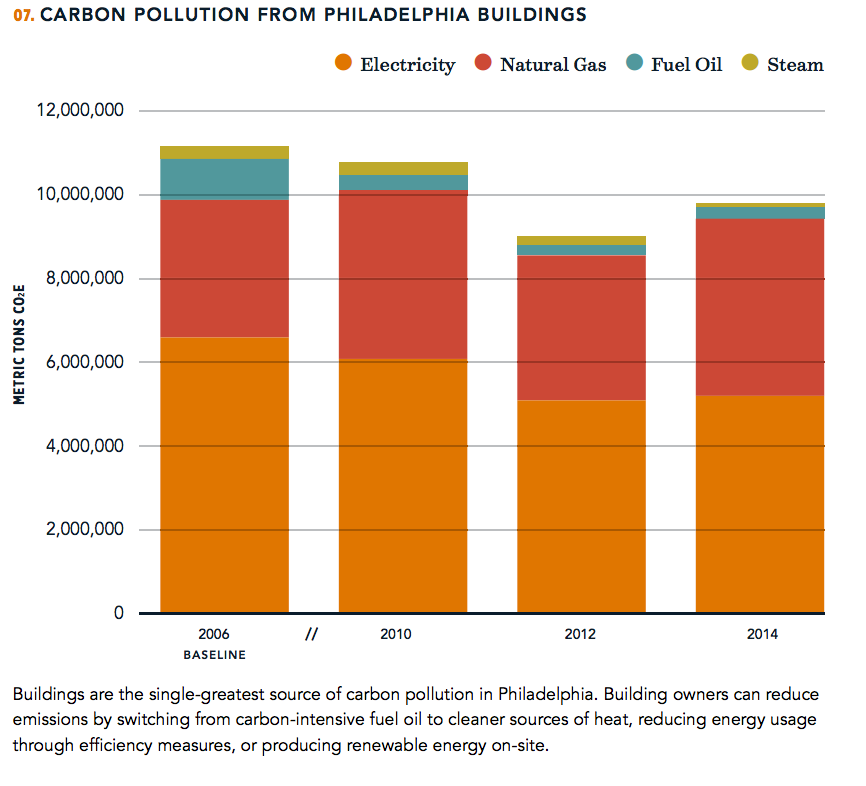

Buildings are the single-greatest source of carbon pollution in Philadelphia, according to the City of Philadelphia Office of Sustainability, and are responsible for 60 percent of citywide carbon emissions.

“Right now, buildings are contributing to the problem, but strategies for reducing energy use in buildings is part of the solution,” Bartolotta said. “The city has a goal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 80% by 2050. If you want to make strides in reaching that goal, reducing greenhouse gas emissions from the building sector is a really good target area to focus a lot of resources on.”

According to DVGBC, Philadelphia 2030 District will be launched in October, and the goal is to start with a district representing 10 million square-feet, of which they already have 7.5 million committed. The initiative would have owners and managers from buildings larger than 50,000 square feet (already participating in the city’s benchmarking program) sign on to meet the goals on an individual level, but progress would be measured on a district level. Based on the experience of other cities, this creates an exchange of knowledge of what conservation strategies are most effective.

“Building this community in Philadelphia will really bring benefit,” Bartolotta said. “There’s information that folks have, the benchmark, but there’s still a need to go beyond that point of recognition and have them learn strategies to reduce their energy use.”

The DVGBC points at the Philadelphia Ronald McDonald House as an example. That project received an honorable mention in the 2014 Energy Reduction Race, a voluntary citywide challenge to reduce energy consumption by 5 percent over the course of one year, for surpassing the target set by the Office of Sustainability.

Barry W. Owen, director of facilities for the Philadelphia Ronald McDonald House said told PlanPhilly that by replacing incandescent lights the building’s electricity use dropped by about 10 percent, and reprogramming thermostats and adjusting the boiler to maximize its cycle reduced natural gas consumption by roughly the same amount. Installing diffusers in all their faucets cut water use too.

Owen calculates the investment in an instrument to regulate the boiler is going to pay back in two years and the light replacement in two or three, but after that’s paid he calculates that Ronald McDonald House will be saving between $3,000 to $5,000 a year.

“The incentive in the long-term is you’re going to save dollars, and that’s important,” Owen said. “You also have to take seriously the need to look for sustainable ways to conserve the environment”.

The real state company Brandywine Realty Trust also participated in the Energy Reduction Race and, according to a statement sent by the company, its Two Logan Square building, reduced its energy usage by 15.4% in one year saving “hundreds of thousands of dollars in annual energy costs.”

LED lighting on the roof and in mechanical spaces, shorter HVAC operating times, energy-efficient lighting upgrades by a major tenant, and participation in voluntary energy load reduction during peak demand times all helped achieve the significant energy reductions, Brandywine’s statement explained.

Building a sort of “cool kids” club that building owners and managers can be part of is really valuable, Emily Schapira, executive director from the Philadelphia Energy Authority (PEA), told PlanPhilly. It builds a community instead of trying to achieve these goals individually. “There’s a ready pool of building owners you can go talk to,” Schapira said. It also sends a strong message to energy services companies and energy lenders. “We are very supportive of creating a 2030 District here in Philly.”

The starting point for the 2030 challenge for every district is the national average/median energy consumption of commercial buildings as reported by the 2003 Commercial Building Energy Consumption Survey (CBECS). With a baseline that’s 13 years in the past, the goals are attainable, Bartolotta said. Building owners are already thinking about reducing energy consumption, and it just requires minor upgrades such as lighting replacement and implementing operation strategies such as lease agreements to engage tenants on their energy use. The DVGBC is working on which water and transportation emissions metrics to use as the challenge’s baseline.

In addition to the 2030 challenge, “Advancing green building: A policy framework for Philadelphia’s built environment” includes other recommendations to mitigate and adapt to future climate impacts, such as including a resilience checklist as part of the city’s permitting process for new buildings and incentivizing energy modeling for new buildings. But for Bartolotta, perhaps the most urgent are a series of action steps to update building codes in Philadelphia. Because Pennsylvania’s Uniform Construction Code (UCC) requires all municipalities to adopt the state’s building codes, Philadelphia hasn’t been able to use the 2015 International Code Council (ICC) standards and is still under the 2009 ICC standard.

“There are just different construction standards now that, based on what we know from the standpoint of technology and building science, makes them more efficient, but we are not required to use that here,” Bartolotta said. “If you could raise the floor of your minimum construction standards, that makes a huge difference, especially with the volume of construction in Philadelphia and the volume of major retrofits also.” According to Advancing Green Building, there’s nearly 40 million square feet of new development in Center City and University City alone.

In 2016, City Council passed a resolution urging the state to allow Philadelphia to pass its own construction codes. The Philadelphia Energy Authority has been advocating in Harrisburg to get Pennsylvania’s building codes up to date, Schapira said, because the existing code does not do enough to encourage energy efficiency, and because Philadelphia has “fallen well behind the national standard and all of our peer states.” In June 2015, the Clean Air Council tried to sue Pennsylvania in an effort to force the adoption of updated building codes.

DVGBC recommends the city promote above-code building standards and certifications such as Leadership in Energy & Environmental Design (LEED), Passive House, Living Building Challenge and WELL Building Standard.

Among the ways to encourage higher-performance buildings, the framework suggests that the city offer development bonuses for projects built to different green design standards, facilitate land bank transfers for high-performance buildings, create pathways for historic structures to go through energy retrofits, and to adopt an ordinance that requires a minimum diversion percentage of the weight of construction and demolition debris to reduce waste.

“As we continue to advocate [for code changes at the state level], this is exactly the right way to approach it,” Schapira, told PlanPhilly. “And this gives the city a lot of good ideas.”

DVGBC is currently using the policy document in meetings with members of the Philadelphia City Council, and will give a presentation on Friday, January 20th at a public event called “Inaugurating Change: A Renewed Commitment to Better Buildings”, with guest speaker State Rep. Leanne Krueger-Braneky.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.