Philly jails expand use of medication to treat inmates with opioid addiction

The average jail stay for inmates in Philadelphia is about 100 days — and Dr. Bruce Herdman, the system's chief medical officer, sees that as an opportunity.

Listen 2:17

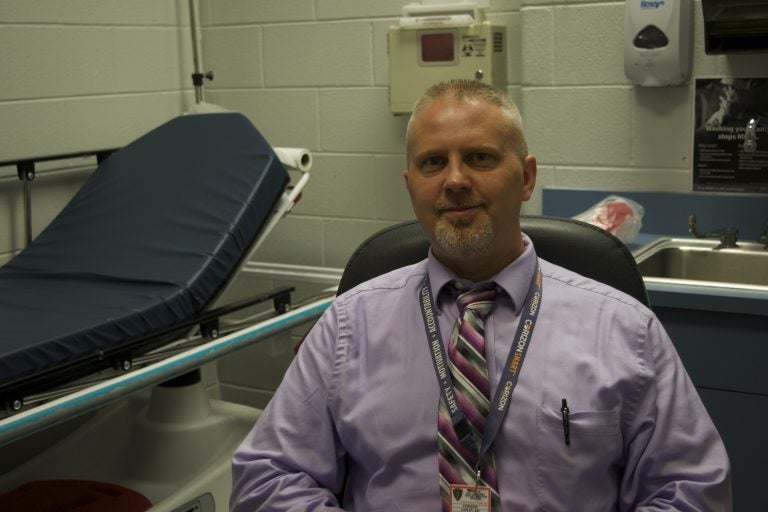

Dr. Jon Lepley, director of infirmary and addiction medicines at the Philadelphia Department of Prisons. (Nina Feldman/WHYY)

In the two weeks after they’re released, formerly incarcerated people are 12 times more likely to die than the average citizen.

And they are 130 times more likely to overdose because, in the case of opioid users, their tolerance level diminishes while they’re behind bars.

“If that individual goes back to using the amount of drugs they’re accustomed to using, their risk of death from overdose is extremely high,” said Dr. Jon Lepley, director of the infirmary and head of addiction medicine at the Philadelphia Department of Prisons. Three quarters of the 28,000 people incarcerated in Philadelphia each year have a substance use disorder.

According to a recent survey of active drug users in the neighborhood of Kensington, conducted by the city’s Department of Public Health, 40 percent had been incarcerated within the past two years.

Because of that overlap between people who use drugs and those most often incarcerated, the city’s Department of Prisons is taking another step to treat inmates with opioid addiction.

Last year, it began sending people home from jail with naloxone, the overdose reversal drug.

In February, it began offering buprenorphine, often known by its brand name Suboxone, to its female inmates since that population is smaller than the men. Starting Monday, male inmates will be offered the prescription that reduces withdrawal symptoms. The move will make the jail system the largest provider of medication-assisted treatment in the city.

The average jail stay for inmates in Philadelphia is about 100 days — and Dr. Bruce Herdman, the system’s chief medical officer, sees that as an opportunity.

“Although it’s regrettable that there are so many people here, it does give us the chance to care for people that are not getting cared for in the community,” he said.

Indeed, prisons and jails can offer a unique chance for detox and recovery for people addicted to opioids.

“People can’t leave treatment the way they do when someone’s in an inpatient facility,” said Lepley. “Whereas here, they certainly can refuse the medication, but they are here, for better or worse.”

Beginning in 2017, Rhode Island’s prison system began offering the full panel of evidence-based medication-assisted treatments: naltrexone (often known by its brand name, Vivitrol); methadone; and buprenorphine or Suboxone. A recent study confirmed that once the panel of medications was in place, overdoses fell slightly among former inmates.

Since February, about 60 female inmates were treated with Suboxone at any given time in Philadelphia’s system. The overall male population is three or four times larger — so, Lepley is preparing for a big endeavor. Adding to the challenge is that restrictions and certification requirements make it difficult for doctors in and out of prisons to be able to prescribe the drug.

Lepley calculated that the system has the capacity to treat 615 patients.

“It cuts it close,” he said.

Finding the balance

Buprenorphine is essentially a very low-dose opioid that can prevent the cravings that come from withdrawal. While the latest research suggests that Suboxone is among the best clinical treatments for opioid addiction, it can get a bad rap because of the potential for its misuse.

Inmates have been known to hide the tabs in their cheeks and sell them.

It is sold as a street drug as well, although because it has a “ceiling effect” — substantially lowering the potential for overdose — it serves more to prevent withdrawal symptoms than to bring on an intense high the way heroin or other more potent opioids would. Still, there is a market for it.

Lepley said there is a strict protocol for administering the daily dose within the jail.

Then, when an inmate leaves the jail, Lepley prescribes five days’ worth of Suboxone, and connects the former inmate with a treatment facility to continue the regimen. From there, he said, it’s up to them.

“Some patients might not take the medicine, they might sell the medicine to continue to use heroin,” he said. “So it’s hard to find that balance between making sure the treatment is available when they leave, but also being responsible with how we’re prescribing opioids.”

As it begins providing Suboxone to male inmates, the Philadelphia Prison System will offer all three of the “gold standard” forms of medication-assisted treatment. Each has advantages and disadvantages, depending on the individual.

Methadone is offered through a contract with nearby Northeast Treatment Center, while Vivitrol or naltrexone is distributed on a limited basis through a study with Penn Medicine.

Staying alive

Herdman said it is critical to coordinate a “warm hand-off” with treatment providers on the outside.

“Traditionally, medical care in prisons has been defined as within the walls, but that’s sort of wasting the investment in the person,” he said.

But Herdman also acknowledged that tracking whether that’s happening is difficult. A statewide prescription database allows officials to see if the Suboxone prescriptions were filled once an individual is released, but not all the treatment facilities participate in that database.

Herdman said he hopes that Community Behavioral Health — the city’s Medicaid provider for mental health and substance abuse, which funds medication-assisted treatment in and out of the jail — eventually will be able to help them track aggregate numbers to measure success.

Lepley, however, said success should not be based on whether someone kicks an addiction or stays out of from behind bars. For him, the goal is reducing overdose deaths.

Even if someone decides she wants to use heroin the day she is released from jail, having been on Suboxone during her time served would prevent her tolerance from dropping, making her less likely to overdose.

“They’ll go out, they’ll come back in, and people are using that as an example that the treatment didn’t work,” he said. “And quite the opposite: The person’s alive. So it did work.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.