15 billion gallons of raw sewage and polluted stormwater makes its way into Philadelphia’s waterways every year, according to new report

PennEnvironment is calling for a more swimmable and fishable city, free of sewage related bacteria and viruses.

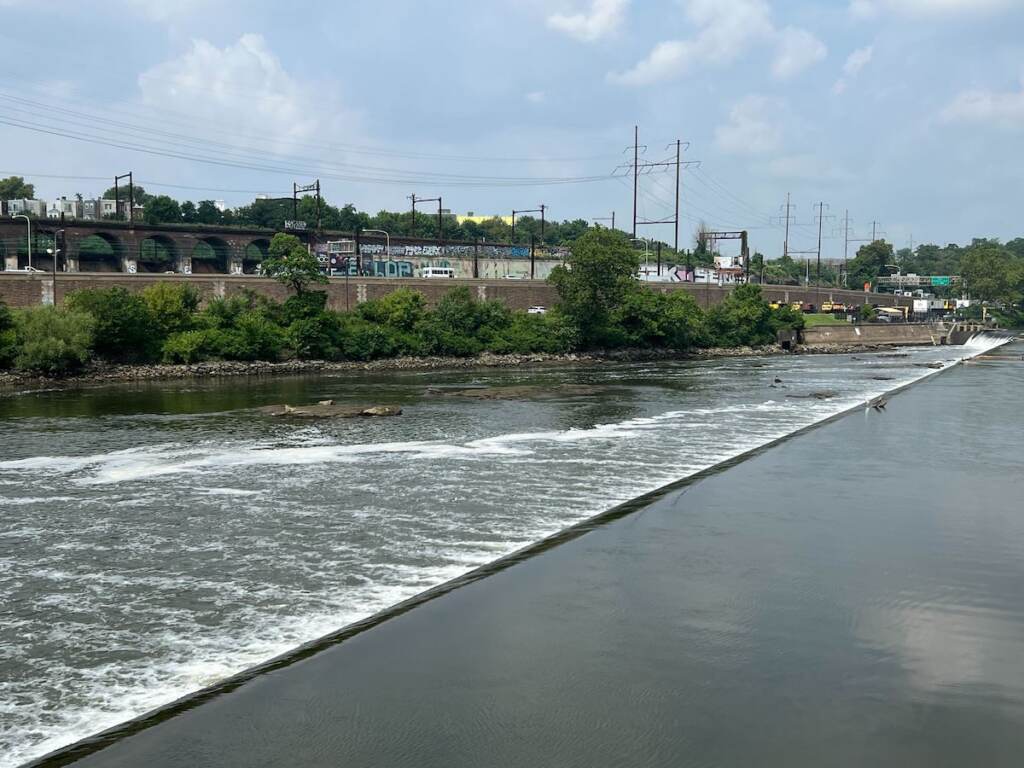

As much as 15 billion gallons of raw sewage enters Philadelphia’s waterways per year, according to PennEnvironment. (Zoë Read/WHYY)

As much as 15 billion gallons of raw sewage and polluted stormwater makes its way into Philadelphia’s waterways every year, according to a new report by PennEnvironment.

The environmental research and advocacy organization is calling for a more swimmable and fishable city, free of sewage related bacteria and viruses.

“Many of the city’s waterways, like the Delaware, and the Schuylkill, they’re unsafe to boat in, to float on,” said Stephanie Wein, clean water advocate at the PennEnvironment Research & Policy Center. “So we’re calling on the water department to speed up [plans to prevent sewage overflows] and to make sure that every day is a day that people can get out on the river.”

Much of the city’s stormwater and sewage flows through the same underground pipes, and is sent to treatment plants. During heavy rain, the system can overflow, spilling sewage into the rivers, which makes it a health hazard to swim, fish, or even kayak. These combined sewage systems are common among older cities, while newer cities have designed separate systems for stormwater and wastewater.

Some sections of Philadelphia utilize separate pipes for sewage and stormwater. However, sewer overflows can still happen when there are system blockages or failures. These types of releases are common in the U.S. — as much as 23,000 to 75,000 times per year, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Overflows in Philadelphia occur so often that the city’s waterways are unsafe for recreation about 128 days a year, reports PennEnvironment, which analyzed the data reported by the city’s water department. The Cobbs and Schuylkill watersheds received the most significant amounts of sewage in 2022, with Delaware, Frankford, and Tacony watersheds not so far behind.

Bartram’s Garden, a botanical garden situated along the Schuylkill River, cancels about a quarter of its aquatic programs because of sewage overflows, said its river program director Valerie Onifade.

State and federal regulations require the city to reduce 85% of stormwater and sewage overflow. In 2011, the city launched a 25-year plan, known as Green City, Clean Waters, to reduce the amount of sewage entering the city’s waterways by using green infrastructure and expanding stormwater treatment capacity.

In a statement, the city said it has made much progress — reducing overflows by 3 billion gallons by utilizing technology composed of natural elements such as rain gardens to soak up stormwater.

A spokesperson for the Philadelphia Water Department said additional projects, including a new pretreatment building at the Northeast Water Pollution Control Plan, will reduce combined sewer overflows by an additional 600 million gallons annually in the next three years. The city has received a $100 million, low-interest, federally backed PENNVEST loan to help finance this project and reduce impacts to ratepayers.

In the statement, Water Department spokesperson Brian Rademaekers added that there are “far more barriers to swimming in urban rivers and streams than those posed by sewer overflows following storms. Even in a dry start to the summer, there have been two tragic drowning deaths in Philadelphia streams this year.”

Tim Dillingham of the American Littoral Society believes the city should demand increased federal funding to help improve its sewage and stormwater systems. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law could provide additional resources, he said.

“It’s no coincidence, I think, that Black and brown communities are the communities that polluted water flows through,” Dillingham said. “This is all a question of investment. Do we care enough about the river, or do we care enough about the cities to make that investment?”

Bacteria, parasites, and viruses in sewage can cause illnesses, such as intestinal infections. Studies estimate that each year, about 90 million illnesses in the U.S. are caused by water recreation.

A Temple University study found significant health risks associated with swimming in Cobbs and Tacony creeks, particularly following rainfall. Heather Murphy, a public health professor at Temple University, does not recommend swimming in the Delaware River watershed. However, the health risks of fishing in Philadelphia can be minimized by hand washing after handling fish.

“I understand people want to spend time in the waterways. People reside close to them, they want to cool down,” Murphy said. “[It’s about] assessing your risk and trying not to get that water in your mouth, and having appropriate hand hygiene is a good idea.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.