Philadelphia rolls out plan to put social workers in city schools

Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney announces a program that will put trained social workers in public schools to help students deal with trauma. He is joined by Commissioner of the Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health David T. Jones (left) and Philadelphia schools Superintendent William Hite. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

When some kids in the School District of Philadelphia return to school next month, they may notice some new faces.

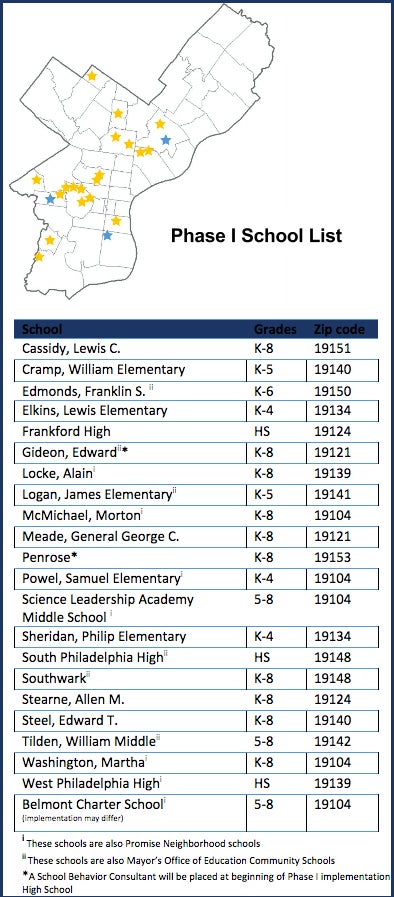

A pilot program is placing social workers in 22 schools to help kids with behavioral challenges.

The Support Team for Education Partnership, or STEP, grew from Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney’s monthly meetings with school principals. He said he kept hearing how children were struggling with behavioral issues and schools were asking for help.

“What we want to do is to try to figure out what it is that’s the root of the problem, the root of the acting out, the root of the meltdown and try to fix it and try to address it,” he said.

At a press conference announcing the project at the School District of Philadelphia, Kenney said the program will give much needed help to students and to teachers and school administrators.

“It takes all the attention away from the classroom or from the administration of school because we have one child that’s in distress and it’s just a terrible situation,” he said.

Licensed social workers with a master’s degree will be part of phase one. In later phases, a behavioral consultant, case manager and family peer specialist will be added to the team.

The project is a partnership between the city, the school district and the city’s behavioral health department.

The main purpose is to look at youth “who are at-risk for behavioral health challenges, as well as to help determine those students who are really in need of behavioral health treatment,” said the department’s commissioner David Jones.

The goal is to help students overcome the challenges that interfere with academic achievement.

“Keeping our children out of crisis is the most important thing that we can do,” said School District of Philadelphia superintendent William Hite. “Sometimes, you cannot educate a child who is in crisis or experiencing trauma. This gives us the ability to do and provide those supports.”

The 22 schools selected are mostly Kindergarten through eighth grade, along with three high schools and one charter. These sites were chosen because they have a large number of students who were already being sent to the crisis center or asking for these services.

The program is expected to cost $1.2 million, but officials say it will be funded by reallocating current resources.

“These are our schools. These are our kids,” Kenney said. “If we continue to utilize the city resources in this regard … our schools will be better places. We’re not asking Harrisburg for anything more. We’re just doing a better job in taking care of our kids.”

The School Reform Commission will be voting Thursday on the plan.

Seven of the schools, located in the federally designated West Philadelphia Promise Neighborhood, will be funded through a U.S. Department of Education grant managed by Drexel University.

Currently, there’s one crisis team for all of the district’s 220 public schools –and if that team’s unavailable, the school calls 911.

Kimlime Chek-Taylor, principal of South Philadelphia High School, says social workers can identify students’ needs immediately.

“They can streamline services for what our students need and what our family needs for them to be successful in the classroom,” she said.

She says before it was “almost like a guessing game.”

“Depending on the situation, we can have four adults who are supporting a child that’s in crisis and that can be a few hours too,” Chek-Taylor said. “I’ve been in places where it took the whole day with four staff members. So having the person there that’s trained will be a heavy lift for us.”

Andrew Lukov, principal of Southwark School, says schools now usually act when a child’s already having a meltdown, endangering himself or others.

“We want to have as much of a proactive approach as possible and this can support that,” he said.

He says schools need to move beyond “maintenance.”

“We do everything we can to get through that day ultimately to keep moving that kid along. That’s not good enough,” Lukov said.

He has a counselor for 800 kids and likes the idea of a team approach.

“This is a victory for our children.”

Kenney hopes to eventually roll the program out to all of Philadelphia’s public schools.

“How realistic is it not to address the needs of these kids?” he said. “They’re going to wind up in juvenile court or going to wind up in foster care. Going to wind up in jail, God forbid. There’s a large cost at the end of that road. If we can stop that progression when they’re in third grade, we have a better shot at producing or helping this person come and meet the potential that was intended for them. If we don’t pay attention to something we just push it aside, we’ll deal with it in the end.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.