New Philadelphia police headquarters sculpture recasts city seal with focus on Black history, abolitionists

The design for the sculpture commissioned for the new Philly police headquarters was altered following the 2020 protest over the killing of George Floyd.

Listen 1:45

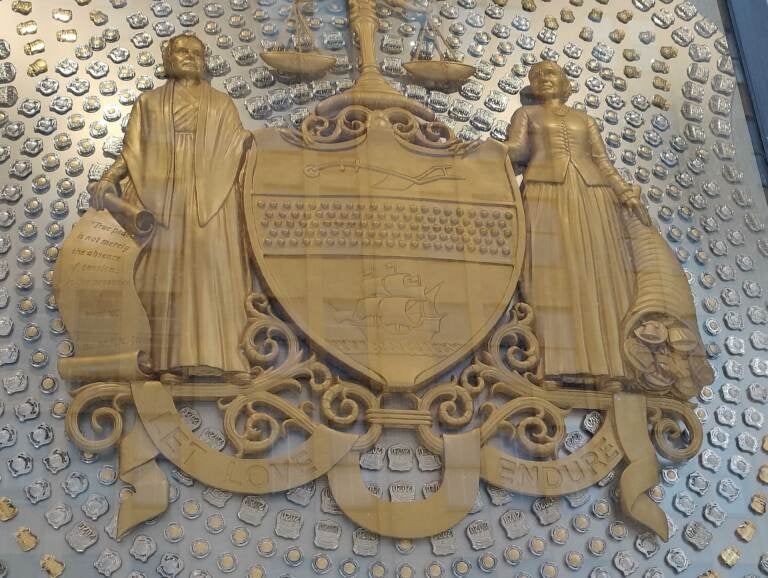

The sculpture at the new Philadelphia police headquarters centers on Black history, abolitionists (Peter Crimmins / WHYY)

The Philadelphia Police Department is moving into its new headquarters on North Broad Street, in the former Inquirer newspaper building. As police officers and administrators walk through the front door of what is now the Police Public Safety Building, they will pass by a giant police badge, nine feet tall, hanging in the window.

If they look closely at the sculptured replica of a police badge, featuring the official city seal at the center, viewers may notice that it does not look like a standard badge.

Historically, the city seal has featured two allegorical female figures representing concepts of Peace and Plenty, but the figures in this sculpture are real, historical Philadelphia women representing the city’s actual abolitionist and Black history: suffragist Lucretia Mott and Black poet Frances Harper.

The sculpture, called Let Love Endure, by artist Donald Lipski, was commissioned as part of the city’s One Percent for Art program, which mandates that 1% of renovation costs of the public building must be spent on public artwork.

The design that Lipski originally submitted three years ago and was approved by the Office of Arts Culture and Creative Economy and the city Arts Commission, did not look like it does now. His original plans took cues from the police department’s symbolic explanation of the badge, as stated in its own directive: “The Police Officer’s Badge represents honor, integrity, truth, and justice. The law enforcement badge is a symbol of service to the community.”

But since the sculpture design was approved, much has changed.

“When I first designed the piece, which was in 2019, I was thinking of the badge as a symbol of protection, a shield,” Lipski said. “After George Floyd was murdered by police [in 2020], I really was taken aback. I thought, if I make a giant shield and put it in the window of the new police building, people will throw rocks at it. For half the people in Philadelphia, the badge really is not a symbol of protection. They don’t see it as a shield.”

Lipski pointed specifically to the long legacy of Frank Rizzo, who was police commissioner from 1968 to 1971 and then was elected to two terms as mayor.

“His administration was really known for police brutality and for being very, very tough on the Black community,” said Lipski. A monument dedicated to Rizzo was removed from display in 2020.

In an attempt to make the sculpture more inclusive and offer respect to a greater number of city residents, Lipski made several last-minute changes to the seal that has officially represented the city since 1789.

The most prominent changes are the faces of the women figures flanking the central shield. On the left representing Peace is now Lucretia Mott, a prominent 19th-century abolitionist who fought for women’s rights. After not being allowed to attend an international anti-slavery convention in London in 1840 because of her gender, the Quaker joined other women in Seneca Falls, New York in 1848 for the first women’s rights convention.

The Seneca Falls convention would ultimately lead, more than 70 years later, to the passage of the 19th Amendment that gave women the right to vote. However, many Black women in America still faced racist state policies that effectively barred them from voting.

As the figure of Peace in the new city seal, Mott is holding a piece of paper written with words from Martin Luther King, Jr.: “True peace is not merely the absence of tension, it’s the presence of justice.”

On the right side of the city seal, representing Plenty, is Frances Harper, who picked up the torch for abolition and suffrage after Mott. Harper founded and led many national progressive efforts, including the National Association of Colored Women. She was also a poet and one of the first Black women in America to publish a novel. She died nine years before women won the right to vote in 1920.

Traditionally, the figure of Plenty is shown with a loaded cornucopia spilling over with food. Here, Lipski made Harper’s cornucopia spill with tokens representing housing, medical care, education, and justice.

Lipski made one more significant change to the original sculpture design. The texture of the enormous badge is made from 1,400 life-size police badges representing every rank. Each badge is stamped with the year 2020.

To Lipski, the year 2020 was a historical turning point in America.

“I thought, this is a year that’s really going to go down like 1776,” he said.

Not only was it the 150 anniversary of the 15th Amendment giving Black men the right to vote, and the 100 anniversary of the 19th Amendment giving women the right to vote, but 2020 was the year of a pandemic that upended American society, and of the police murder of George Floyd that spurred a global protest movement.

“I would hope that the police going through their classes, being taught this, and then coming to work in a building where there is this badge with Francis Harper and Lucretia Mott and 2020 all over it – all these symbols of everything I hope a police badge should represent,” said Lipski. “Maybe it’ll affect them. Maybe it’ll make some of them consider: ‘This really is something I have to live up to.’”

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.