A Philly photographer captures the glory days of the Black cowboy

Ron Tarver has been taking pictures of Black horse culture for 30 years, in town and country.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

When Ron Tarver first photographed Jordan Bullock in 1993, he was just a 12-year-old kid growing up in North Philadelphia who was mad for horses, just like his old man, Bumpsey Bullock, who ran the White House stables in Brewerytown.

Jordan is now 43 and has built his life around horses. He’s a racehorse trainer, keeping a half dozen stalls at the stables of Parx Casino and Racetrack in Bensalem.

“This is all I ever knew. It was normal my whole life,” Bullock said. “That’s what we did on weekends and after school, it was my father and my aunt, my cousins, one of my uncles. My mother’s side of the family — by total chance, my parents did not know this when they met each other — but my mother’s side of the family is in horses in Virginia.”

Bullock appears as a child in Tarver’s new book, “The Long Ride Home: Black Cowboys in America,” representing a time in Philadelphia’s urban history when horses were everywhere. Many neighborhoods in North and West Philly had stables.

“You had the White House. You had 32nd Street, at 32nd and Master which is literally up the street from us,” Bullock said. “You had the Hole in the Wall, which was a stable where they literally broke a hole in the wall of a warehouse and built a stable.”

“You have Fletcher Street, which is on Fletcher Street. You have Uber Street, which is actually the Big Muddy. That’s what they call it because the yard was always muddy,” he said. ”You had Goats. Goat was a person and a farm on Ridge Avenue near Andorra, which is now houses. 48th Street is not even on 48th Street. It’s on Parkside Avenue, but that’s just what it’s called. Same thing with Sammy’s. There’s, like, a whole culture.”

Tarver spent years during the 1990s following Philadelphia’s Black cowboys as they cared for horses in their stables, went on rides through Fairmount Park’s 57 miles of trails, and took trips to Manhattan. He also traveled across the country seeking similar Black horse cultures.

“Jordan’s dad was an amazing man,” Tarver said of Bumpsey Bullock “There’s a photo of him that I shot in Harlem. He’s sitting on this horse and on Lenox Avenue and there’s a cop car behind him. He looks like a monument. He was a monumental man.”

Tarver, a former staff photographer for The Philadelphia Inquirer who now teaches at Swarthmore College, has been photographing Black cowboys for 30 years. He started at Bullock’s White House stables while on assignment for the newspaper in 1992, which ran as the cover story in what used to be the Inquirer’s Sunday magazine.

“When that story ran I got more email — or I should say mail, this was way before email,” Tarver corrected himself. “I got more snail mail from readers than any story that I’d ever done.”

The success of the photo essay prompted Tarver to ask his editor to send him across the country to take pictures of other Black cowboys scenes. He went to Oklahoma, where Tarver grew up around Black horsemen, Texas and California, to rodeos and stables and ranches.

That became a week-long series of photo essays that ran in the Inquirer in 1993, earning Tarver a Pulitzer Prize nomination (he would win the prize almost 20 years later, in 2012, for a team reporting effort on violence in public schools). National Geographic gave him a grant to keep shooting photos of Black cowboys.

Flush with success, Tarver sought out a book deal in the 1990s, knocking on doors of New York City publishing houses.

But nobody was interested.

“In fact, one acquisition editor told me, ‘I don’t think there’s such a thing as Black cowboys,’” Tarver recalled. “I said, ’I got about 20,000 slides says there are.’”

Since then, Black cowboys have entered the mainstream. Rapper Lil Nas X released the smash hit “Old Town Road” in 2018, a hit that played with a Black western aesthetic. Beyoncé also released her “Cowboy Carter” album this year, stepping into the country genre.

Earlier this spring another photography book was released, “Eight Seconds: Black Rodeo Culture,” by Ian McClellen, whose Instagram account eightsecs has attracted more than 27,000 followers with its photos of Black riders.

In 2022, the film “Concrete Cowboy” starring Idris Elba brought the image of Philadelphia’s Black horsemen to the big screen. Filmmaker Jordan Peele (“Get Out,” “Us”), riding on the coattails of his own Black horseman thriller “Nope” (2022), is producing a documentary series about Black cowboys for the Peacock, NBC’s streaming service.

This year, the Bill Pickett Invitational traveling Black rodeo celebrates its 40th anniversary as a nationally touring event. The oldest Black rodeo, the Roy Leblanc Okmulgee Invitational, held its 69th rodeo this summer in its hometown of Okmulgee, Oklahoma.

“I think it is more prevalent now because it’s out in the zeitgeist,” Tarver said. “You can’t have better notoriety than Beyoncé coming out with an album. The ‘Cowboy Carter’ album just blew everything up.”

“It became accepted, but there’s still a little bit of prejudice out there when it comes to what’s accepted as country and what’s not accepted,” he said. “I’m hoping that this book will just add to the conversation.”

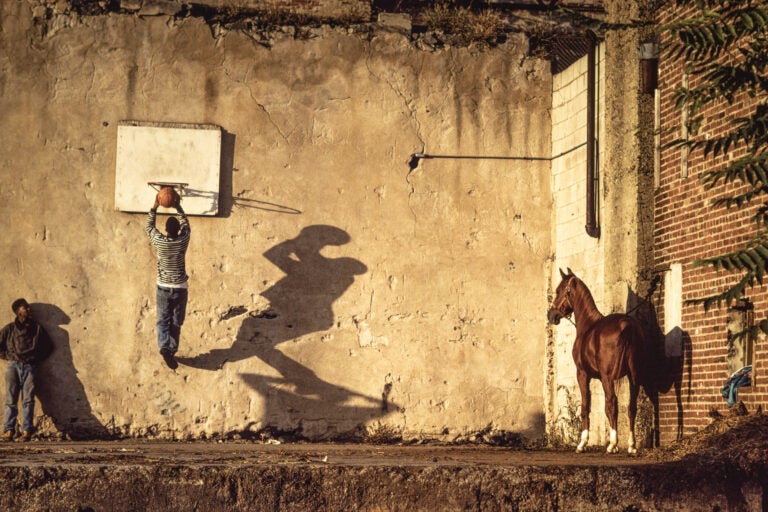

“The Long Ride Home” sticks to Tarver’s early photography from the 1990s, showing Philadelphia’s urban horsemen playing basketball in a dirt lot while their horse watches; a young boy in Texas wearing full western gear — with a belt buckle nearly the size of his head — doing rope tricks; and two women in Oakland, California, cleaning a leather saddle on the hood of a beat-up Subaru.

Tarver took a picture in 1993 of a demure court reporter in Oakland dressed in a heather gray suit dutifully notating a trial being argued in court. That’s her day job. The facing page shows the same woman dressed in western regalia, gritting her teeth in fury while riding a rodeo horse.

There’s nothing demure about her on top of the horse. The page spread is a Jekyll-to-Hyde transition.

“You’re on top of a 1,500-pound animal going 40 miles an hour. You have to share the same intensity that horse shows,” Tarver explained. “The horses know. They know if you don’t know what you’re doing. They’ll throw you in a second.”

Aside from an introductory essay in which Tarver explains the origins of the photos in “The Long Ride Home” and another essay tracing the history of the Black cowboy by Art T. Burton, a retired professor of history at Prairie State College in Illinois, very little is explained. Most of the people in the photos are not identified, only the location and the year of the picture.

Tarver did not set out to tell the story of the Black cowboy. He wanted the vintage shots from 30 years ago to speak for themselves.

“I didn’t want to have a documentary book. I wanted to have a book that celebrated the lifestyle of Black people who share this western heritage,” he said. “Just, for lack of a better word, beautiful images of this lifestyle and people enjoying this culture.”

For Jordan Bullock, these images from his childhood era remind him of what is not there anymore. Most of those stables he names are not there anymore. The old-timers have died, including his own father from COVID-19, taking volumes of accumulated horse knowledge with them.

“My world is rapidly dying,” he said. “You do get kids coming around that want to learn, but the sad part is that they don’t have the elders that I had. I’m the older guy now. I’m 43, but I grew up with guys who were way older than that. I’m really the last of the Mohicans.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.